Transformation through information: Building resilient communities in Chennai

This blog is part of a series on how open government can help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The series came out of a collaboration between the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Bangkok Regional Hub and the Open Government Partnership (OGP) to find practical examples of how open government is helping countries achieve the SDGs in the Asia-Pacific region. For more details on the competition, the blog series, and how open government can help achieve the SDGs, please see our introductory blog post.

Raji is 19 years old and works as a waste picker in one of Chennai’s landfills. She quit school when she was 15, married another informal waste picker when she was 16, and now has an 18-month old baby. Raji does not have an identity card and her work is illegal under current legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r..., which criminalizes collecting waste from municipal bins and waste yards. She is unable to access public services, including day care for her baby – so she brings it with her everyday to the landfill, wrapped in newspaper. The city of Chennai generates approximately 5000 metric tonnes of mixed garbage every day, and it is waste pickers like Raji, who pick out the recyclable materials, thus diverting large amounts of waste from the city’s overflowing waste yards. However, the Greater Chennai Corporation, the city government, does not have a number for how many informal waste workers there are in the city. It also lacks accurate data on the composition and quantities of waste that is granular enough to make meaningful public policies with regard to municipal waste and waste workers.

This is a typical governance challenge in urban settlements across developing countries. Often, governments are unable to provide adequate infrastructure and services to people due to a lack of resources. Even when they have sufficient resources, and allocate money for a specific service, the lack of relevant information (particularly data about the informal sector and poor, marginalized communities) hinders the ability of governments to frame policies and provide public services. This is why, even though open government initiatives hold the promise to transform governance by enhancing transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More and accountability, their success is impeded by the lack of credible data and poor capacities to use them.

It is in this context that the Transparent Cities Network (TCN) works to transform governance with information. TCN, an initiative housed at the Citizen Consumer and Civic Action Group (CAG), an NGO in Chennai, India, works to make cities and human settlements safe, inclusive, resilient and sustainable. Initiatives like TCN are key in advancing progress on several Sustainable Development GoalsOGP countries are experimenting with open government innovations to accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 16+ which includes peaceful, just and inclusive societies...: Goal 11 on sustainable cities and communities, Goal 10 on reducing inequalities, and Goal 16 on building just and peaceful societies through transparent and accountable institutions. The objectives of TCN are threefold: 1) to build a shared understanding among relevant stakeholders about the lack of information about the poor that can be used for planning, implementation, monitoring, and advocacy; 2) to create a widely shared and credible set of responses to the information gap on the urban poor; 3) to support and strengthen existing advocacy, planning, and interventions on issues facing the urban poor by our civil society, community, and government partners through the use of data, maps, and participatory methods.

Among our initiatives are our efforts to create data on three important urban services: drinking water in slums, identity cards for informal waste workers, and route and fare information for an informal paratransit service.

Aside from the lack of tenure security, a key challenge faced by slum dwellers is the lack of basic services, such as water and sanitationOGP participating governments are in a unique position to address many of the root causes of water issues, including corruption and poor quality, as well as lack of prioritization, access, equity, and.... In November 2015, TCN provided methodology support and training to an NGO in Mumbai to work with youthRecognizing that investing in youth means investing in a better future, OGP participating governments are creating meaningful opportunities for youth to participate in government processes. Technical ... More in a slum community to collect Geographic Information System (GIS) data, which was used to create visualisations that show ‘black-holes’ of water access in the areas selected for the study. The survey uses a novel, community-based participatory research model, with data collection by barefoot researchers (youth living in the slum community) who measure household access to safe drinking water, data that official statistics do not have. This empowers local communities to hold the local government accountable for improving water access. The aim is also to pilot methods for assessing ‘actionable’ water service delivery indicators in slums to show the government how and where water infrastructure is non-functional, deficient, or non-existent using GIS mapping of water infrastructure.

Another urban challenge that Indian cities are faced with is meeting solid waste management needs in the face of rising consumption, crumbling infrastructure and under-performing service providers. The lack of data on the informal sector has abetted the perpetuation of exploitative relationships, as well as labour and environmental abuses in sections of the informal network. TCN is working to compel the city and state governments to reduce inequality by including marginalized groups in the creation of data and maps on informal waste workers and their contributions to making our cities more liveable. In July 2015, following a successful campaign for the issue of identity cards to informal waste workers, we worked with the Greater Chennai Corporation to organize registration camps for informal waste workers at the two dumpyards. The registration process was unique because we used tablets to complete personal information, capture photographs and also the signatures or thumb prints of the waste pickers (Image 1). These identity cards would not just make visible the invisible face of Chennai’s desire for cleanliness; they would also serve to protect their access to livelihoods.

Figure 1: A waste picker inserting his thumb print on his personal information card.

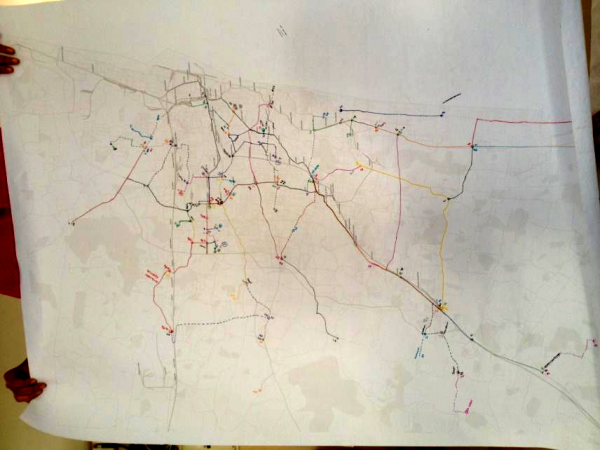

Share autos (tuk tuks) are an important informal paratransit service in most Indian cities; there are nearly 5000 share autos in Chennai on approximately 100 routes. They are popular because of their flexibility and because they provide transport services in areas not serviced by formal public transportation. They are inexpensive in comparison to taxis, and passengers can board and debark at any point on the route. Despite their significance in the city’s transit options, there is no formal governance mechanism; nor is there any publicly available data on numbers, routes and fares. We chose to work with the drivers to synthesize this information. Due to the lack of internet connectivity in their trade union office, we used an A0 size city map with road networks and major transport landmarks (Image 3). Each route was marked with a route number and further identified with a color and line legend. It took two paper-mapping sessions with to enumerated 70 routes operating in the city, covering most parts of Chennai (Image 4). We intend to integrate this with other modes of transport and enable commuters to made transit choices that would take them from door to door using only public transport, both formal and informal.

Figure 2: A group of waste pickers waiting for their turn to register. In the background the waste in the dumpyard.

While our primary beneficiaries are marginalized and disadvantaged communities, municipal governments are also beneficiaries of our work. In the past, TCN researchers have worked closely with street-level bureaucrats in the Greater Chennai Corporation to plan for new public toilets by helping them collect geospatial data and use it along with data on availability of land, and water and sewerage connections. In numerous instances, we have used open source mobile applications that simplified the process of collecting data and used open source tools to visualize it. The data, maps and methodology provided simple practical tools that the city’s de facto planners can use to improve project creation and implementation. We also embarked on a collaboration with Nagpur Municipal Corporation, the city government of Nagpur City, to identify barriers to the equitable provision of municipal services. These could be because of poor spatial distribution of the services, or could arise from poor planning processes that do not recognize the socio-economic factors that disadvantage certain communities.

Figure 3: Mapping share auto routes with union members.

Our engagement with the government ranges from maintaining an arms-length relationship to signing multi-year partnership agreements. To affect change, we build partnerships between city governments, civil society groups, academics and practitioners for each of the types of projects, studies and campaigns we undertake. In this way, we are able to forge specific alliances among stakeholders who often disagree. By using data and maps, we enable communities and government officials to transcend individualistic, transactional relationships to more meaningful, constructive collaborations. We also support the media by enabling data-driven journalism and reporting on critical urban development issues.

Figure 4: A map of 70 auto share routes mapped on an A0 size city map.

The main innovation of the initiative is that it combines data, technology and participation to address critical urban challenges, particularly those that disproportionately affect the urban poor. The strength of this initiative lies in building an understanding of the critical roles of data and information about the poor, creating a set of credible responses to overcome these information gaps, and in strengthening advocacy for improved urban governance through the use of data, maps and participatory methods. One of our key principles is to use open tools and methods. The other is to always provide digital and non-digital ways to create data, and extend technical support to marginalized groups that do not have access to technology so that that is not the barrier to their participation. In addition, we build the capacities of groups in other contexts to develop their ability to deploy such approaches. However, a critical factor of the approach is the engagement with communities and governments, and this cannot be easily replicated.

###

Previous pieces in our OGP-UNDP Series can be found here:

- Check My Service, Mongolia

- Community Initiatives for Common Understanding, Nepal

- Citizen Satisfaction Index, Pakistan

- Environmental Governance, China

- Check My School, Philippines