Introduction

Evidence continues to show that open government affects people’s lives. But there are still skeptics who are not aware of all the benefits associated with this approach. Are you struggling to convince others to take an open government approach when implementing reforms? Are you looking for concrete evidence on the impact of making government more transparent, accountable, and participatory? Then, this guide is for you.

In this guide, you will find evidence on how open governments improve business efficiency, lower corruption, deliver better quality services, and much more. Unlike other reports, this guide is based on current, mostly peer-reviewed research, in each of the policy areas included. Experts around the world collaborated for rigorous reviews of current social science in and beyond Open Government Partnership (OGP) member countries.[1] In each section, you will find a link to read the underlying papers. The OGP Support Unit and partners will continue to update this guide, with forthcoming chapters on additional open government policies. Visit this site often for new insights on the benefits of open government.

Organization

This guide translates what is often technical research language into points of evidence you can use. The report is divided into 6 sections. Each section features the following:

- DEFINITIONS of key terms;

- EVIDENCE OF IMPACTS of a specific open government policy on development outcomes in non-technical language;

- CASE STUDIES of instances where governments learned about how policies worked through specific reforms or experiments and that draw lessons than can be useful for other contexts; and

- LIMITS TO THE EVIDENCE that readers should consider. While this report aims to be easy to understand, it also needs to be clear about what we collectively do not know yet and what we cannot claim about open government results.

What’s Inside

This guide includes easy-to-grasp evidence on the impacts of some of the most popular and successful open government policies. This guide teaches how:

- Access to justice benefits the economy and restores the social contract;

- Fiscal openness can lower corruption and raise revenue;

- Grievance redress mechanisms in the public sector can improve governance and services;

- Social audits can improve public service accessibility and trust in service providers; and

- Open contracting can increase cost savings and competition.

You will find answers to questions such as:

- How does participatory budgeting help governments save money?

- How do grievance redress mechanisms empower women?

- How does a people-centered approach to justice help businesses?

….and much more.

How to Use This Guide

With evidence from this guide, you can:

- Create a value proposition for open government reforms in your agency, advocacy strategy, or organization;

- Inspire reforms and commitments;

- Include examples of results in a reformer’s speech;

- Use social media to share this evidence and reach a broader audience; and

- Foster synergies between government and academia to evaluate reforms and understand how to make open government work better for everyone.

What’s New in the Second Edition?

This guide is a follow-up to the first Skeptic’s Guide to Open Government, published in 2018. The 2018 edition looked at the general impacts of open government. Alongside an update to this evidence, this second guide takes a deeper look into the impacts of specific open government policies. Taking this approach, no skeptic’s guide could cover every policy in open government. For that reason, this edition focuses on a set of policies where there was clear priority from OGP’s leadership and a large body of peer-reviewed scholarship on impacts. Some areas, such as natural resource governance may deserve a chapter, but were not included to keep the project timely and manageable. Partner organizations inspired by the model can reach out to [email protected] where they have ideas for future chapters.

This guide is a follow-up to the first Skeptic’s Guide to Open Government, published in 2018. The 2018 edition looked at the general impacts of open government. Alongside an update to this evidence, this second guide takes a deeper look into the impacts of specific open government policies. Taking this approach, no skeptic’s guide could cover every policy in open government. For that reason, this edition focuses on a set of policies where there was clear priority from OGP’s leadership and a large body of peer-reviewed scholarship on impacts. Some areas, such as natural resource governance may deserve a chapter, but were not included to keep the project timely and manageable. Partner organizations inspired by the model can reach out to [email protected] where they have ideas for future chapters.

What is Open Government?

People often ask how OGP defines “open government.” The OGP Articles of Governance, OGP’s founding document, lays out the key values for the partnership. Open governments strive to embrace the following values to improve governance and solve public challenges:

ACCESS TO INFORMATION

Access to government-held information empowers citizens to exercise their rights, hold government accountable, and participate in decision-making. Examples in this guide that highlight how transparency advances progress in key policy areas include:

- Transparent fiscal management and public contracting discourage corruption and enable reformers to follow the money to ensure that public funds are spent efficiently and in ways that benefit citizens; and

- Providing access to justice information can help citizens better understand their legal problems and the resources available to solve them.

CIVIC PARTICIPATION

Civic participation empowers citizens to participate freely in governance, either through invited consultations or by creating space for free expression and assembly. Civic participation also helps make governments more responsive, innovative, and effective. This publication highlights several of the many ways civic participation can advance progress in key reform areas. For example:

- It is often difficult for governments—nationally or locally—to create mechanisms for the poor, women, youth, and other marginalized groups to participate in their community governance. Social audits are productive channels for this type of interaction in a collaborative rather than adversarial format.

- Evidence shows that participatory budgeting at the local level leads to more effective government spending on public services.

PUBLIC ACCOUNTABILITY

Public accountability refers to rules, regulations, and mechanisms that allow citizens to demand that government actors justify their actions, act upon criticisms or requirements made of them, and accept responsibility for failure to perform with respect to laws or commitments. Evidence in this guide highlights ways in which citizens can hold their government accountable. For example:

- Audits of public budget execution near election cycles give citizens valuable information to decide on whether to reelect incumbent officials.

- Grievance redress mechanisms allow citizens to correct government failures in fulfilling a legally mandated right.

“To open up governance, to be held accountable, is not a favor to civil society, to development partners or to the party. It is an imperative to create a stronger, healthier nation.”

Richard “Bon” Moya, 2016.

This guide is dedicated to the memory and legacy of Richard “Bon” Moya, a tireless advocate for open government.

Access to Justice

This chapter is based on a background paper by Mark Weston developed to support the Skeptic’s Guide with guidance from Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just, and Inclusive Societies.

The Benefits of Providing Access to Justice for All

Investing in open and accessible justice institutions benefits the economy and societies. Access to justice allows citizens to better defend their rights, demand access to public services, and protect their ability to participate in democratic processes. Justice is an essential element to reducing barriers for underserved communities. National-level institutions, such as ministries of justice, as well as ground-level institutions like court systems and legal assistance organizations and informal mechanisms, all play a role in delivering justice services and should be engaged in designing solutions to people’s justice problems.[2]

A people-centered approach makes justice institutions more open and accessible. Figure 1 outlines the components of this approach.

Definitions

- ACCESS TO JUSTICE – the ability of people to resolve and prevent their justice problems and use justice as a platform to participate in their economies and societies.[4]

The Evidence

Here is what the evidence shows on how inadequate access to justice causes different outcomes and how improving access to justice can avoid those impacts.

EQUALITY

- People with low income have disproportionately more justice problems. Low-income groups tend to experience significantly more serious legal issues.[5] In Australia, disadvantaged groups—including people who belong to indigenous groups, single parents, people experiencing homelessness, people receiving government benefits, people in unemployment, and people with disabilities—are two to four times more likely than people who do not belong to these groups to experience problems related to fines, and they are more likely to lack the financial and legal capability to resolve them.[6] People in these disadvantaged groups often leave these problems unresolved, which leads to debt and to compounded disadvantage.[7]

- People with low income are also less likely to resolve their justice problems. A 2020 survey in the United States found that, while 52% of wealthy households successfully resolve their legal problems, only 44% of households with an income below $25,000 per year do so.[8] This survey defines resolution as the extent to which a problem is resolved and the result is enforced.[9]

- Women face unique barriers to accessing justice. The World Justice Project’s 2018 General Population Poll of 45 countries found that 53% of surveyed women experienced a legal problem in the two years prior to the survey. Yet, only 13% turned to an authority or third party to help solve the problem.[10] This might be explained by the gender discrimination, social stigmas, unawareness of rights, and economic disadvantages that women face.

- Women and men are not treated equally in the judiciary system in some countries. An assessment of 189 countries found that 16 still give less evidentiary weight to women’s testimony in court than men’s.[11]

FAIRNESS

- An increase in peer-appointed judges leads to more impartial judicial decisions. In Pakistan, a reform that changed the selection procedure for judges from presidential appointment to appointment by peer judges was associated with a significant reduction in court rulings in favor of the government. For every 10% increase in the number of peer-appointed judges, the number of wins for the state declined by two percentage points.[12]

- Legal representation leads to more positive outcomes:

- In Australia, a study found that when people who belong to disadvantaged groups[13] received assistance to resolve problems related to fines, the outcomes of their cases became similar to those of people who do not belong to a disadvantaged group.[14]

- In a qualitative study in the United Kingdom, asylum seekers that were represented by a lawyer at appeal hearings were significantly more likely to succeed in their appeals.[15]

- Data from more than 18,000 court cases in the United States shows that individuals who were represented in immigration court cases were more than 30 percentage points more likely to be successful in avoiding removal from the country than those without representation.[16]

HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

- Justice problems might lead to consequences beyond the legal problem itself. The World Justice Project’s 2018 General Population Poll in 101 countries found that 29% of respondents experienced health problems as a result of their justice problems.[17]

- Justice problems bring financial difficulties to individuals:

- In the United States, individuals who experience justice problems often lose money, have negative effects on their financial well-being, or lose their job. The costs associated with resolving these justice problems range from USD 1,750 to USD 6,000, depending on the type of problem.[18]

- A 2019 survey found that, in Uganda, almost half of the individuals who experienced at least one legal problem reported having suffered a loss of income as a result, while one in ten lost their job.[19]

DECENT WORK

- Effective social reintegration improves economic prospects for ex-offenders. A study in Michigan, United States found that when ex-offenders had their criminal records sealed from the public (“expunged”) their potential wages increased by more than 22% compared to periods before expungement.[20]

CASE STUDY

Skills Training in Australia Reduces Recidivism

ACTION: The Fairbridge Bindjareb Project provided Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were imprisoned with training on the skills needed by the local mining industry before they were released from prison and helped them find employment.

IMPACT: Only 18% of participants re-offended within two years of release (compared to the 40% recidivism rate for the aggregate prison population) and almost three-quarters were still employed seven months after the program ended.[21]

CASE STUDY

Reducing French Labor Courts Stunts Job Creation

ACTION: In 2008, the government decided to cut the number of labor courts by one-quarter, representing longer distances for workers and employees to litigate employment disputes.

IMPACT: The job creation rate was four percentage points lower and the firm creation rate was six percentage points lower in cities that were now farther away from labor courts than in unaffected cities.[22]

ECONOMIC GROWTH

- Weak access to justice is a drain on the economy. An analysis of data from 44 countries found that, in 39 countries, the annual cost of legal problems is equivalent to at least 0.5% of their GDP. In 29 of those 39 countries, the costs amount to at least 1% of GDP, while in nine—including high-income Greece and Portugal as well as low-income Ethiopia, Malawi, and Nepal—they exceed 2% of GDP.[23]

- More judges means faster growth. In a study on the number of judges per capita in 83 countries between 1970 and 2014, it was found that increasing the density of judges by 1% was associated with a 0.17 percentage point increase in annual per capita GDP.[24]

- Faster dispute resolution means more growth. In India, improving court efficiency in contract enforcement cases was found to be associated with greater productivity of manufacturing sectors. A 2018 study found that “reducing the average age of pending cases by a year would, on average, increase a state’s aggregate productivity by about three percent”.[25]

CASE STUDY

Legal Assistance for Kenyan Farmers Increases Productivity

ACTION: A randomized experiment provided a free lawyer to a group of Kenyan farmers working in areas with a high prevalence of land disputes and limited access to formal justice institutions.

IMPACT: Because of the increased predictability of the economic environment, farmers with legal assistance increased their production by 42% and their investment by 21% compared with those who received no assistance.[26]

REVENUE

- Investing in justice pays dividends. Calculations made in the United Nations and World Bank’s Pathways for Peace report conservatively estimated that countries that increase delivery of core justice functions and expand access to justice can gain a return of $16 for every $1 invested by reducing the prevalence of violent conflict.[27]

- Without dispute resolution, governments lose revenue. In 2015 in New Orleans, United States, the city spent $1.9 million more on detaining people who could not pay fines or fees than the revenue received from the fines and fees that were ultimately paid.[28]

- Innovations decrease defaults on payments. In Michigan, United States, implementing an online platform that allows for online payment of fines and fees was associated with a 19 percentage point decrease in the likelihood of default on payments.[29] Introducing this technology benefited both individuals and jurisdictions, as it reduced the time it took for citizens to resolve their disputes, increased the percentage of payments the courts received, and reduced the time for courts to receive them.[30]

- Pro bono assistance means government savings. An evaluation of “Pro Bono Ontario” in Ontario, Canada, showed that its pro bono legal assistance was associated with cost savings and economic benefits to the province of $5.76 million Canadian dollars, a return of $10 for every dollar invested.[31]

- Legal representation saves money. A cost-benefit analysis of legal representation for low-income tenants facing eviction in Philadelphia, United States, found a benefit to the city of $12.74 for every $1 invested associated with the savings of averted evictions.[32]

TRUST

- Positive perceptions of law enforcement are linked to trust in other types of institutions. A survey of people from 27 European countries found that in settings where police officers are perceived to behave fairly, levels of trust in political institutions are higher.[33]

- Positive contact with law enforcement officers builds confidence. In Connecticut, United States, a field experiment showed that positive contact with a uniformed police officer could improve attitudes about the police. For this random experiment, households were assigned to a treatment group (receiving the intervention) or a control group (not receiving the intervention). Police officers visited people in the treatment group in their homes using strategies that nurture positive contact and gave them their business cards. Baseline and follow-up surveys showed that people in the treatment group had more positive attitudes and confidence in the police.[34]

PUBLIC SAFETY

- A weak justice system undermines the social contract. A survey of people from 25 European countries showed that the quality of justice systems affects people’s likelihood of breaking the law. Three indicators of judicial quality—the independence of a country’s judiciary, the impartiality of courts, and protection of property rights—were found to be significantly related to individuals’ propensity to offer bribes to officials, falsely claim government benefits, make false insurance claims, or knowingly buy stolen goods.[35]

CASE STUDY

The International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala Inspires Law and Order

ACTION: In 2006, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was established with a mandate to investigate individuals involved in corruption and organized crime.[36] While it did not have prosecutorial powers, in its 12 years of operation, it assisted in filing more than 120 cases in the Guatemalan justice system, including the prosecution of two former presidents. Additionally, the CICIG helped Guatemala boost important reforms to the justice system and improve capacity-building of local investigative authorities.[37]

IMPACT:

There was a sharp decline in the country’s homicide rates between 2008 and 2016. In comparison to other 11 similar Latin American countries, it was found that the CICIG helped prevent at least 18,000 murders and that the country’s homicide rate would have doubled in the absence of CICIG.[38]

● The impunity rate in the country was found to have fallen from 98% of cases in 2006 to 70% nine years later.

● Guatemalans expressed that they trusted CICIG more than the Constitutional Court or the Public Prosecutor’s Office.[39]

CASE STUDY

Justice Services for Women in Peru Decrease Gender-Related Crimes

ACTION: Peru implemented Women’s Justice Centers (WJCs), which are staffed mostly by women and provide women with police, medical, and legal services.

IMPACT: In communities with WJCs, reporting of gender-based crimes increased 40% and gender-based violence, femicides, and female deaths due to aggression declined by 10%. Children living in households near a center became significantly more likely to attend school and less likely to drop out.[40]

Limits to the Evidence[41]

- There are ethical implications to more robust research methods. More robust evidence could be obtained by increasing randomized control trials. However, these are scarce in the justice field, perhaps because of their cost or the ethical implications of having a control group that does not benefit from the intervention.

- The impacts of informal justice mechanisms are under-researched.

- The effectiveness of legal empowerment and the provision of people-centered justice services is under-researched. More research will help us understand if, when, and how these mechanisms help.

- Researchers could make more use of “natural experiments,” such as policy changes due to COVID-19.

- There is a lack of standardized methods for measuring the impact of increasing access to justice.

- Evidence on the impact of access to justice in particular sectors such as the impact on children and their education, the impact on violent conflict, the impact on labor rights and the quality of work, and the impact on businesses is scarce.

“There is no free democracy without independent justice.”

H.E. Luis Rodolfo Abinader Corona, President of the Dominican Republic, Summit for Democracy, 2021 (translated from Spanish).

Fiscal Openness

This chapter is based on a background paper by Martin Haus, Joachim Wehner, and Paolo de Renzio developed to support the Skeptic’s Guide in partnership with the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency and the International Budget Partnership.

The Benefits of Fiscal Openness

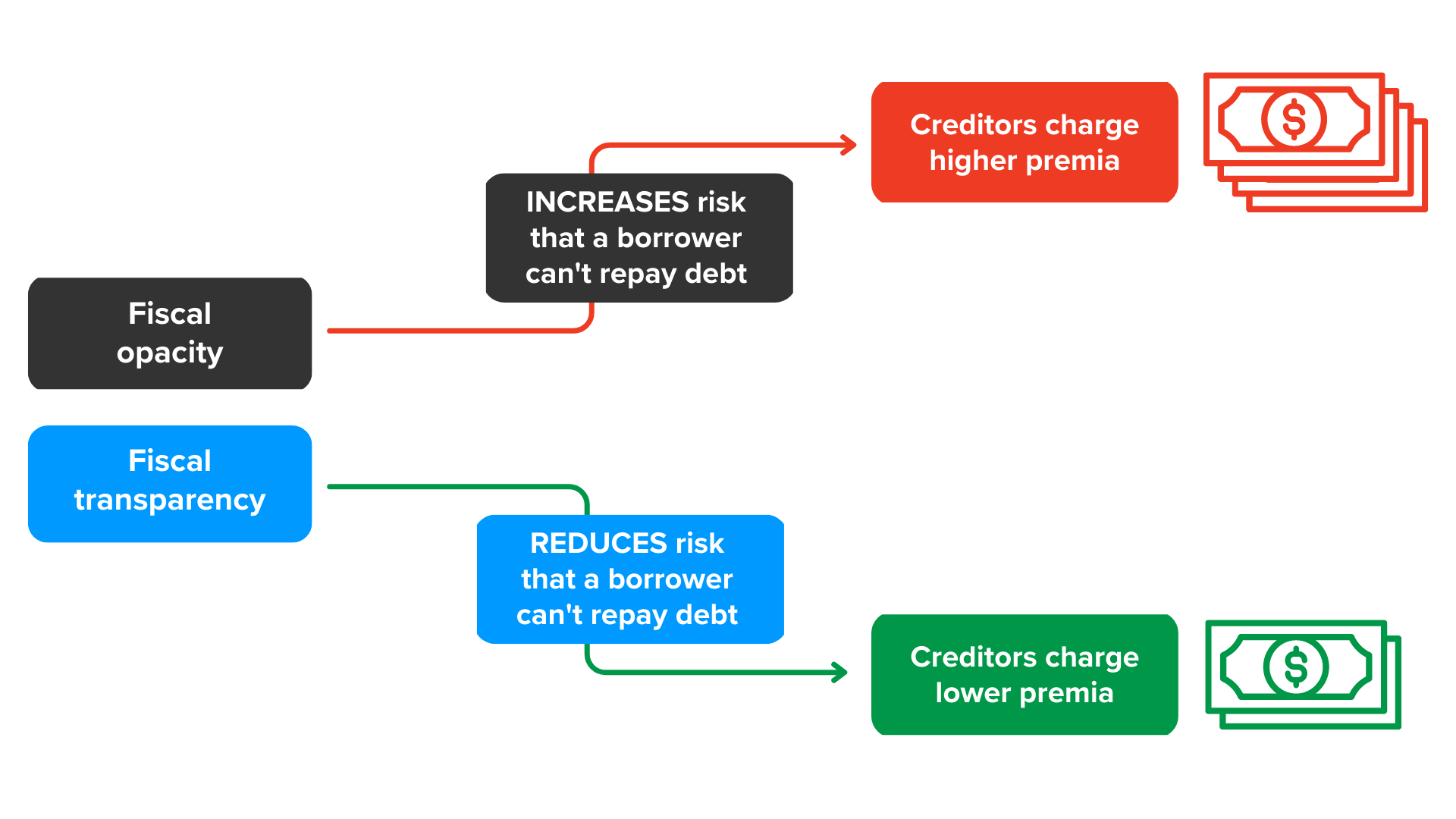

There is growing evidence that shows that transparency, participation, and accountability in fiscal matters lead to lower corruption, more revenue, and better government services.[42]

Definitions

- FISCAL OPENNESS OR BUDGET OPENNESS – government action that ensures transparency and citizen engagement at any stage of the budget cycle. This includes transparency and participation in spending and revenues as well as deficits and debt.[43]

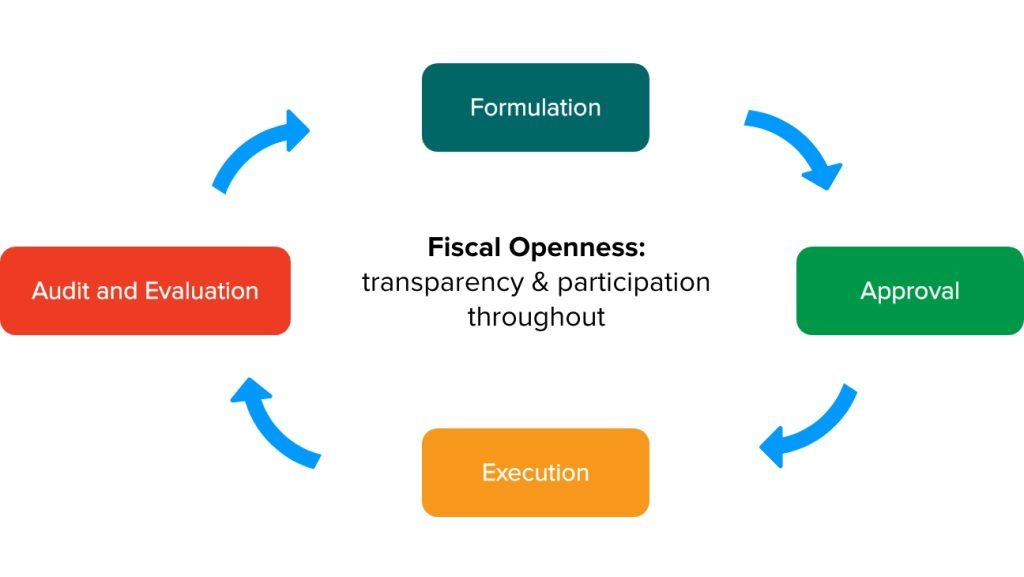

- BUDGET CYCLE – the budget cycle covers the formation, approval, execution (including procurement), and audit and evaluation stages of budgeting.[44] (See Figure 2 for a simplified description of the budget cycle.)

- PARTICIPATORY BUDGETING (PB) – a deliberative process in which community members decide how to spend part of a public budget.[45]

The Evidence

Fiscal openness can benefit individual citizens, societies, and governments. Here is what the evidence shows about how fiscal openness impacts areas such as health, control of corruption, and public security. This chapter includes case studies that support the evidence as well as future areas for research on fiscal openness.

CONTROL OF CORRUPTION

- Community monitoring can reduce leakage of public funds. A study[47] of Indonesian road projects suggests that community monitoring alone can be as effective in reducing corruption as top-down audits,[48] and almost three times as cost-effective.[49] The study finds that when government institutions conduct top-down audits in tandem with community monitoring, members of the community become unmotivated to participate.[50]

- Expecting an annual audit reduces corruption. In Brazil, increasing the likelihood of an annual audit by 20 percentage points reduced the share of procurement processes with evidence of corruption by about 15 percentage points.[51] Audits, even internal audits, are foundational to more open government.

REVENUE AND SPENDING

- Participatory budgeting is associated with higher government revenues. A study in Brazil[52] compared municipal governments with participatory institutions (i.e., policy councils and participatory budgeting) to those without them and found that those with participatory institutions had higher tax revenues. The study also found that these municipalities’ rate of tax collection increased as time went by.

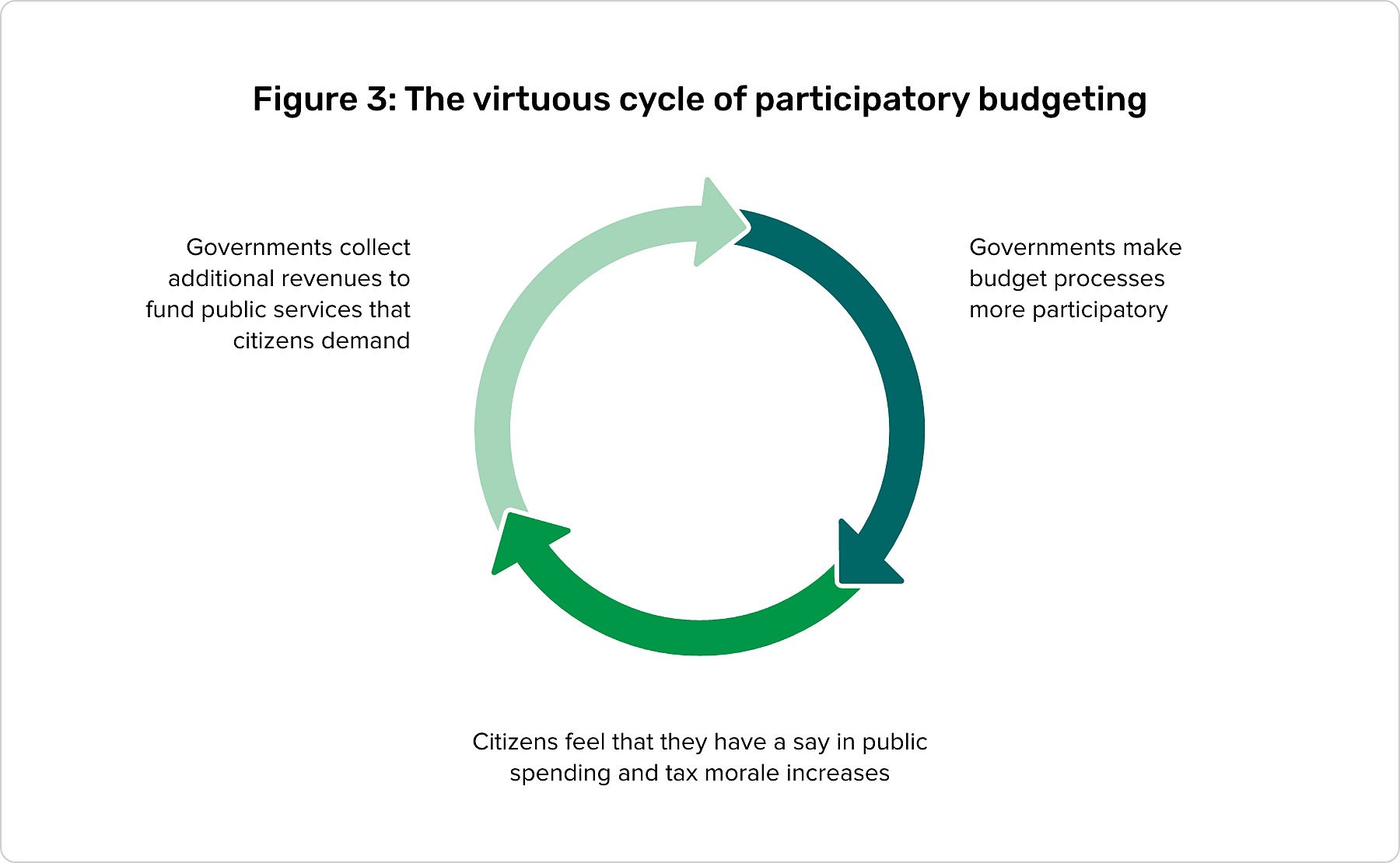

- Participatory budgeting increases “tax morale” and leads to a virtuous cycle. A survey across 50 countries found that tax morale, which is citizens’ willingness to voluntarily pay taxes, increases from 5.07 to 5.23 on a scale from 1 to 8 when they are able to express their preferences on public spending.[53] This suggests that PB prompts a virtuous cycle, in which governments foster citizen participation, citizens feel involved and pay more taxes, increasing government revenue to implement the projects that citizens demand.[54] Figure 3 illustrates this virtuous cycle.

Participatory Budgeting: A Virtuous Cycle

Participatory budgeting can set off a virtuous cycle of good governance, with citizens paying more taxes as they feel that they have a say in how governments spend public resources, and local governments collecting additional revenues to fund public services that citizens want.[55]

There is growing evidence that shows that more participation is associated with increased tax collection. But, there is also an interesting case study suggesting that better tax collection also improves civic participation. In 2016, the provincial government of Kasaï Central in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) implemented a large-scale door-to-door property tax collection campaign in the city of Kananga. In the neighborhoods where the campaign was implemented, political participation increased by about 5 percentage points and citizens were more likely to attend town hall meetings even when it was costly for them to attend. Additionally, tax revenue increased and the government felt greater responsibility to provide public goods.[56]

CASE STUDY

Participation and Tax Collection in Brazil Increases Tax Revenue

ACTION: Several municipalities in Brazil created “policy councils” (where citizens have a say in local policy) and adopted participatory budgeting (devoting a share of the municipal budget to projects chosen by citizen assemblies).

IMPACT: A study showed that, on average, municipalities collect 2.5% more tax revenue for each additional policy council they create and an additional 16% when they adopted participatory budgeting.[57] These relationships strengthen with time.

CASE STUDY

In Costa Rica, Disclosing Information on Public Investment Projects Increases Efficiency

ACTION: In 2018, the government of Costa Rica, with support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) launched MapaInversiones, an online platform where citizens can see geo-referenced information, make inquiries, and check the progress of public investment projects.[58]

IMPACT: A 2018 experimental study found that projects that were uploaded onto MapaInversiones performed better than projects that were not. Financial progress of public investment projects uploaded onto the platform increased by 18 percentage points, and physical progress increased by 8 percentage points compared to unpublished projects three months after the launch of the platform. The effect was stronger in the short term and for smaller projects.[59]

CASE STUDY

Increased Independence of Auditors in Italy Improves Budget Management

ACTION: Independent accountability, when combined with transparency, can be even more powerful. In Italy, auditors went from being appointed at the discretion of mayors to be randomly appointed instead.

IMPACT: The reform significantly improved budget management and there was an increase in the average net surplus of the overall annual budget of about 1%.[60]

This reform is part of a larger shift toward fiscal openness in Italy. The study that yielded this evidence used detailed open data on all municipal budgets, which included spending and revenue sources, debt repayment, and other variables. The Italian Ministry of the Interior published these data.

PUBLIC SAFETY

- Participatory budgeting allows security concerns to be voiced. A study from South Korea[61] found that budget allocations for surveillance cameras were larger for low-income neighborhoods when the budget was decided through participatory rather than bureaucratic mechanisms. This may reflect a preference in these communities for additional policing.[62]

HEALTH

- Participatory budgeting is associated with lower infant mortality. In Brazil, municipalities that adopted participatory budgeting early saw lower rates of infant mortality. A study found that PB allowed citizens to allocate spending to specific needs, such as healthcare.[63]

Limits to the Evidence

- More research is needed on participation in other stages of the budget cycle. In addition to participatory budgeting, more evidence is needed on the effects of participation, for example, during legislative approval processes and audits.

- There is a need for experimental methods that better reflect reality. While field experiments have been widely used to assess the impact of one-off interventions, natural experiments allow a more holistic assessment of the system-wide impact of openness interventions.

- Understanding why fiscal openness works. Evidence continues to grow that participatory budgeting makes a difference. But questions remain as to why it works and when.[64] Future research is needed to clarify mechanisms and enabling conditions, so that interventions can be designed and deployed more effectively.

- Governments can support research. Governments can support learning about fiscal openness. For instance, staggered and randomized rollout of reforms allows researchers to compare communities where the policy was implemented with the ones in which it was not and evaluate the effect of the policy in similar contexts. Releasing these data into the public domain allows social scientists to creatively evaluate policies and programs. This also enables governments to manage risks and consider adaptations prior to full-scale implementation. These lessons will be valuable to governments themselves, as well as academics and think tanks.[65]

- More research is needed on tracking expenditures as they are being made. An area of joint interest for scholars and practitioners is expenditure-tracking surveys, where a pioneering study about local service delivery and education outcomes in Uganda[66] suggests promising results.

- Some interventions to increase fiscal openness might have unintended consequences. Public officials, aware of likely audits, might temporarily change their behavior to avoid a negative audit, particularly ahead of elections.[67] Officials might reduce corruption in the short term and return to higher levels of rent extraction afterward.[68] Another example of distortion is when public officials obscure activities, such as auctions, to make corruption less detectable.[69] Thus, it is important for researchers to evaluate the impacts of fiscal openness in the long run.

“Democracy is not a spectator’s sport, if you do not participate, then there is no democracy.”

Madeleine Albright, Former U.S. Secretary of State, Open Society Foundations video for the Summit for Democracy, 2021

Open Contracting

This chapter is based on a background paper by Andy McDevitt developed to support the Skeptic’s Guide with guidance from the Open Contracting Partnership.

The Benefits of Open Contracting

Public procurement is one of the largest categories of spending in any country, and the most prone to waste and abuse. Open contracting leads to significant cost savings, internal efficiency, high-quality service delivery, and greater competition.[70]

Definitions

- OPEN CONTRACTING – an approach to reform public procurement policies and processes to increase transparency, participation, and inclusivity (from the planning to the implementation of public contracts) by using open, timely, and accessible data for decision-making, monitoring, and oversight.

- E-PROCUREMENT – the use of information technology in purchasing public goods, works, and services from suppliers.

- GENDER-RESPONSIVE PROCUREMENT – a government commitment to include gender-responsive objectives and actions, redress gender biases, and build internal capacity to implement gender-responsive actions. This may include both measures to support the inclusion of women-led businesses to participate as suppliers and measures to ensure goods, works, and services procured meet the needs of women and girls.[71]

The Evidence

Here is what the evidence shows on the impact of open contracting on public spending, efficiency, quality of public works and services, fighting corruption, and social inclusion.

COST SAVINGS AND ACCELERATED TIMESCALES

- Open e-procurement platforms result in significant financial savings and reduced procurement timelines.

- A 2019 study compared data on competitive procurement processes conducted through ProZorro, Ukraine’s open-source e-procurement platform with competitive procurement processes conducted before the introduction of ProZorro. It found that with the introduction of ProZorro, there was an increased gap between estimated and actual prices (3.5 to 5.8% lower than pre-ProZorro procurements).[72] ProZorro also reduced the time to procure goods and services by around 5 to 6 days.[73] In its pilot phase in 2015, ProZorro was estimated to have saved over USD 55 million for more than 3,900 government agencies and state-owned enterprises across Ukraine.[74] By the end of 2020, total savings stood at an estimated USD 6 billion.[75]

- A 2020 study of Argentina’s e-procurement platform COMPR.AR found that it reduced prices by an estimated 4%, totalling over USD 35 million in savings. COMPR.AR also reduced the duration of the public procurement process by over 11 days and enhanced efficiency, transparency, and data availability. By design, it facilitated public access to information to reduce asymmetry gaps and allow for a larger number of bidders.[76]

- Research by the Open Contracting Partnership in Paraguay estimated increased savings on procurement costs of 1.4% a year after the launch of the country’s open contracting portal and redesign of its procurement portal in 2015. It also found a drop in adjustments and amendments to contracting processes from 19% of all contracts in 2013 to 3% in 2016.[77]

- A 2016 OECD report on South Korea’s ON-Line E-Procurement System (KONEPS) estimated savings of USD 8 billion per year based on savings in administrative costs, mainly through a reduced burden on businesses. KONEPS also reduced the time taken to process government contracts from over 30 hours to 2.[78]

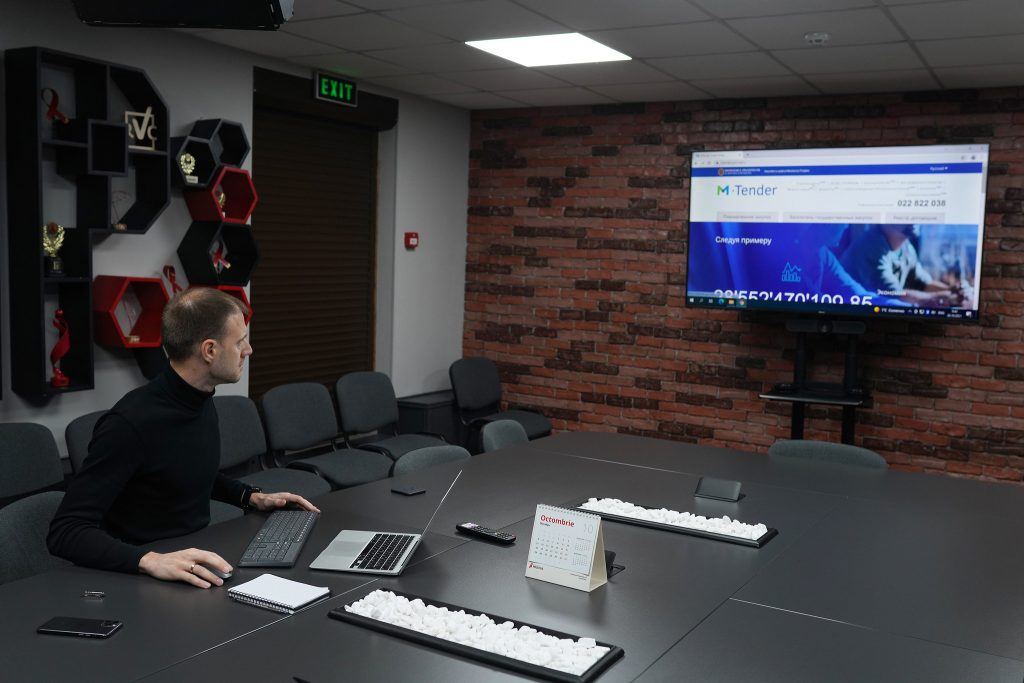

- In Moldova, the medical e-procurement system, MTender, saved 15.4% on transactions worth around USD 60 million. In the country’s HIV/AIDS program, lower-priced generics largely replaced expensive branded medicines, saving 19% on the 2020 HIV/AIDS program procurement budget.[79]

- In Colombia, within one year of implementing the country’s new e-procurement system Colombia Compra Eficiente, the number of days it took to award contracts improved by 16 days on average.[80]

- Publishing cost estimates can increase savings. A 2008 analysis of highway construction projects in Oklahoma, United States, found that the state’s publication of internal cost estimates prior to bid submissions lowered average bids and the winning bid, with stronger effects in more complex and uncertain projects. The policy also allowed new entrants to put in more realistic bids and increased their survival rate in the industry. [81]

- Having a transparent bidder qualification process can reduce procurement costs. A 2009 study of the bidder qualification process in municipal public works auctions in Japan found that improved transparency reduced procurement costs by up to 8%.[82] Studies on Japanese procurement data find that transparency of several items, such as minimum prices, generates greater competition and efficiencies by making collusion of bidders more difficult.[83]

INCREASED COMPETITION

- Publishing contract details can decrease single bidding for contracts. A 2017 study of more than 4 million public procurement contracts in 30 European countries found that publishing additional contract information (items such as criteria details, contract value, and selection method)[84] decreased single bidding across procurement processes. (Single bidder contracts are awarded when only one firm participates in the bidding process, thus making the process non-competitive.)[85] The study estimated that increasing transparency by five items on average could decrease single bidding by 2–3.5% and could save EUR 3.6–6.3 billion across the EU. The study also concluded that pre-award transparency had a stronger effect on corruption risks than post-award transparency.[86]

- Transparent procurement systems attract more bidders. A 2017 World Bank study found that firms are more likely to participate in public procurement markets in countries with transparent procurement systems, where exceptions to open competition in tendering must be explicitly justified. The study also found some evidence that transparent systems also encourage a higher number of bidding firms, in particular smaller firms for whom transaction costs in learning about bidding opportunities are more burdensome.[87]

- Advertising contract opportunities increases competition and yields a high return on investment.

- A 2016 study using World Bank data found that an increase in advertising bid opportunities significantly increased competition (the number of bids). It suggested that a relatively modest increase in advertising and transparency had an economically meaningful impact on procurement outcomes.[88]

- A study in Italy found that online advertisement of bidding opportunities on the national public procurement portal had a positive effect on the number of bidders, prevalence of non-local winners, and price discounts as compared to advertisements in local newspapers.[89]

- Open competition can reduce prices. A 2021 study found open competition leads to 10 to 20% price reduction. Among the reviewed policy interventions, the study found that introducing e-procurement and widening advertisement of opportunities had the most significant effects.[90]

VALUE FOR MONEY

- Civil society monitoring can reduce costs of public works projects. A 2017 field experiment in Peru compared 200 district governments implementing infrastructure projects. Districts that were pre-notified of monitoring by a civil society organization completed the public works at significantly lower costs (51% less expensive) than those that were not. On average, the intervention reduced the cost of public works by approximately USD 75,000 per project.[91]

- Open contracting plays an important role in safeguarding healthcare funds. In the Slovak Republic, the publication of contracting information uncovered considerable inefficiencies in hospital procurement, including the purchase of identical CT scanners for prices that varied by more than 100%.[92]

CASE STUDY

Community Monitoring in the Philippines Improves Textbook Quality and Cuts Price in Half

ACTION: The Philippine Department of Education partnered with local NGOs to monitor the department’s contract bidding process, inspect the quality of textbooks, and track deliveries between 2002 to 2005.

IMPACT: Textbook prices fell by 50%, and volunteer observers reported 95% error-free deliveries. The quality of books also improved as demonstrated by an increase in the average shelf life of textbooks from two to four or five years by 2007. The time for a complete textbook cycle, from bidding to delivery, had shrunk by 50% to 12 months.[93]

CONTROL OF CORRUPTION

- Cross-referencing procurement data with company registration data can help detect corruption. An in-depth 2013 study from Transparency International in Georgia analyzed 430,000 single-sourced/non-competitive government purchases, cross-referencing them with data on company registration, asset declarations, and party donations records. It found at least USD 150 million in single-sourced purchases going to companies owned by members of parliament and public officials or their spouses. In 2012, 60% of donations disclosed by the ruling party came from owners, directors, and lawyers of companies that had received contracts without tenders, with the average donation estimated to be equivalent to 4% of the contract values involved.[94]

- Linking beneficial ownership data with procurement data can reveal conflicts of interest even across borders. Transparency International Czech Republic uncovered a conflict of interest in the Czech Republic using the Slovak Republic’s public register (see the text box below for more details on the Slovak Republic’s register). It found Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš had a controlling share of Agrofert, a large Czech agriculture conglomerate. As the sole beneficiary of two trust funds that owned 100% of the shares of Agrofert, Babiš received millions of euros in subsidies from the EU every year, which was ruled to be a clear conflict of interest by the European Commission.[95]

- Transparency and citizen monitoring can discourage unjust practices. A 2020 study from Ukraine found that transparency and citizen monitoring of the open procurement market was effective in pushing collusive bidders out of the market, which enabled real competition. Bidders collude by setting conditions (costs, number of bidders, among other factors) to favor a specific candidate, thus creating artificial competition. The study found that additional oversight of the procurement process helped reduce prices in the market by 20.6% and it reached an overall welfare gain of between 2.68% and 3.11% of total procurement spending.[96]

CASE STUDY

The Slovak Republic’s Register of Public Sector Partners Improves Integrity of its Public Procurement Process

ACTION: In November 2015, Slovak Republic introduced the public Register of Public Sector Partners for companies participating in public procurement.

IMPACT: Civil society organizations in the Slovak Republic used the register to reveal that 190 of the listed beneficial owners were public officials (who might have a conflict of interest when awarding contracts) and to verify whether companies were providing information on their beneficial owners as part of winning public contracts as required by law. In March 2016, it was found that the public news agency TASR had signed a contract for a computer upgrade worth EUR 110,000 with a company that had not provided its beneficial owner. The same was true for two contracts awarded by a local government. When the new register was launched in 2017, a state-run rail operator was forced to withdraw from a highly criticized 50-year lease of the country’s main train station when citizens discovered that the contractor did not provide information on its beneficial owner.[97]

SOCIAL INCLUSION

Open contracting is a major part of opening up procurement processes to multiple bidders. Opening up the process to more competition can lead to a greater diversity of contractors. In addition, publishing data on the diversity of contractors, their performance, and including more diverse businesses into the design of the tendering process can help identify areas for outreach and improvements to contracting.

- Inclusive procurement can bring concrete economic and social benefits. According to a 2020 report, an inclusive procurement process can support jobs and give governments access to a wider choice of goods, services, and skills, and generate increased competition and economic growth.[98]

- Supplier diversity programs provide value for money. A study found that leading procurement organizations that have a higher adoption rate of supplier diversity programs generate 133% greater return on the cost of procurement operations than average performers, driving an additional USD 3.6 million to their bottom line for every USD 1 million in procurement operations costs.[99]

- Open data can identify gaps of inequalities in procurement. A study of Albania’s procurement data found that contracts awarded to women entrepreneurs tend to be more cost-effective. Nonetheless, although they perform better and 27% of the businesses in the country are owned by women, only 5% of municipal contracts were awarded to those women-run businesses.[100]

CASE STUDY

Empowering Women Businesses in Public Procurement in the Dominican Republic

ACTION: Starting in 2012, in addition to expanding its open e-procurement reforms, the Dominican public procurement agency launched a range of initiatives to increase the participation of women-owned businesses. This included encouraging women to register as suppliers, a new target for 5% of all government contracts to go exclusively to women-owned businesses, and events and workshops to familiarize women with public procurement.

IMPACT: These actions increased women businesses’ participation and winning of contracts. According to data by the Dominican Republic’s public procurement agency, between 2012 and 2017 the number of women suppliers registered in the database grew from 2,000 to 15,000 and by 2019, a fifth of government contracts, totaling RD$20 billion (USD 350 million) went to women.[101] The value of small contracts to MSMEs increased by 600% from USD 6 million in 2013 to USD 42 million in 2019.[102]

Limits to the Evidence

- Geographical scope of the evidence is focused on two regions: Europe (in particular Eastern Europe) and Latin America. Although there is also some representation from other parts of the world including Indonesia, the Philippines, and Kenya, the focus on Europe and Latin America may be explained by the widespread introduction of e-procurement reforms in these regions in the early 2000s. By 2020, over two-thirds of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and 100% of OECD countries had implemented e-procurement systems, often in the form of a central platform. Not all of these have made their data publicly available, however.[103]

- More research is needed on the benefits of linking open contracting and beneficial ownership data. In practice, the systematic use of beneficial ownership data in procurement remains very limited.[104] As a result, there are no ex-post empirical studies to determine the deterrent effect of registers, or a causal link between registers and successful investigations. Nevertheless, anecdotal evidence reveals a small number of cases where beneficial ownership helped detect financial crime.[105] It will be especially important to link this data further with data on political processes including officials’ asset disclosures and political finance.

- Many studies do not provide evidence on the magnitude of the effects of open contracting interventions specifically. This is either because there is insufficient good data to compare outcomes before and after interventions or because the assessed interventions are part of larger reforms including e-procurement and change in bidding structure[106] and hence it is difficult to isolate their effects. Governments can help build this knowledge base by cooperating on natural experiments with researchers.

- More efforts to address structural inequalities are needed. Evidence on the impact of open contracting on social inclusion is largely observational, with results suggesting that the potential for open contracting to contribute to greater inclusion is limited in the absence of wider efforts to address structural inequalities. Open contracting by itself may not bring minority-owned businesses into the process. There are still many barriers, such as lack of access and empowerment, that hinder their participation.

“The pandemic gave us the best incentive possible to promote the values connected to open government. The need to have new inputs of information that can only come from citizens, open data, and collaboration.”

Victoria Alsina-Burgués, Minister of Foreign Action and Open Government, Government of Catalonia, Spain. 2021 OGP Global Summit.

Social Audits

This chapter is based on a background paper by Suchi Pande developed to support the Skeptic’s Guide with guidance from the Accountability Research Center.

The Benefits of Social Audits on Service Delivery

Evidence shows that social audits can improve program implementation, public service accessibility, and trust of service providers.[107]

Definitions

- SOCIAL AUDITS – a tool where citizens can engage and hold government service providers accountable. For this guide, social audits have the following characteristics:[108]

- An information-gathering process to identify the standards or laws that determine citizens’ rights to, and quality of, public services;

- A third-party convening (whether by government or civil society) to assess how policy goals, standards, or laws compare with public sector practice, with an emphasis on access to and quality of services; and

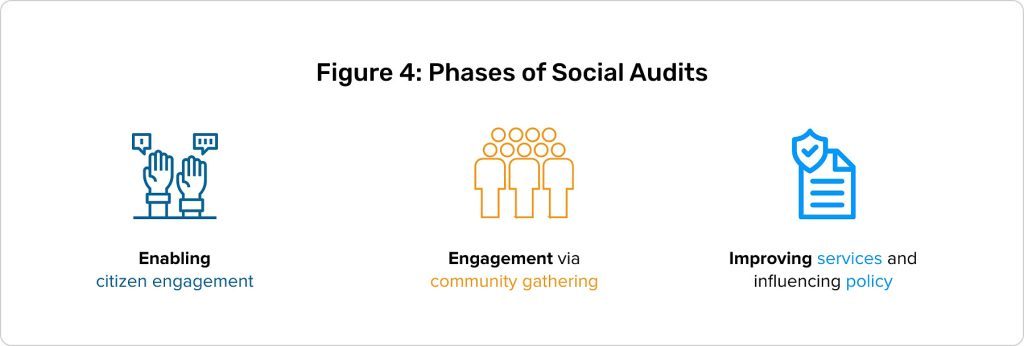

- A public forum where findings from the assessment are discussed, and actionable recommendations are identified, prioritized, and agreed upon. See figure 4 below for an overview of the phases of social audits.

In this guide, we include evidence from two successful social audit approaches:

- Community Score Card (CSC): a type of social audit developed by CARE (Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere) in 2002. This approach includes: identifying the right to services; involving community members and service providers via in-person meetings for discussion and creation of joint action plans; and monitoring and evaluating plan implementation.

- Citizen Voice and Action (CVA): an evidence-based social accountability model developed by international humanitarian aid organization World Vision in 2008. While the practical implementation is flexible, there are four core elements: sharing information about public services; increasing opportunities for citizens to voice feedback and influence decisions; creating opportunities for dialogue and collaboration; and increasing accountability of service providers.

In addition to social audits led by local civil society or international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), there are large-scale government-led social audits. Oftentimes, there are synergies between the different actors managing social audits. This section includes examples of social audits managed by local civil society, INGOs, and governments.

The Evidence

Here is what the evidence shows on how social audits impact public service delivery and how they can raise public awareness about public services and improve trust.[109]

HEALTH

- Social audits increase awareness of available public services and can improve health outcomes.

- In Uganda, community monitoring of primary healthcare providers increased quality and quantity of primary healthcare provision, particularly of child immunizations, waiting times, examination procedures, and provider absenteeism. Additionally, child mortality decreased and average child weight increased in monitored communities.[110]

- In Nepal, a study found that social audits improved the quality of services provided: there was clearer pricing on medicines and treatments, wider awareness of medicine availability in Nepali, clearer hours of operation, and better treatment for maternal health.[111]

- A study in Odisha, India found that social audits can improve delivery and uptake of food and nutrition services. It found that social audits sensitized communities to their rights under India’s national food security law. The study found positive changes in three out of four programs related to maternity entitlement, food distribution, and integrated child development services.[112] As a result of cumulative exposure to the social audit process, participants reported a reduction in extra payments to obtain rations in villages under the food distribution scheme.[113]

- Citizen validation helps to understand gaps and address problems.

- A qualitative study of community health clinics in Bangladesh showed that CSCs positively changed community participation in healthcare, raised community awareness, and generated more revenue for clinics. Study respondents felt that CSCs increased the awareness of clinic services among communities, improved communication between community and health providers, and that the collective effort helped identify and prioritize problems.[114]

- In Nepal, a study showed that social audits identified issues in utilization and availability of services. Utilization of institutional services and immunizations increased. Demand for services increased as the social audit increased awareness of availability and health service entitlements. A frequently raised issue in the early years was inadequate staff or attendance at health facilities; this improved over different cycles of the audits. Similarly, pharmaceutical shortages were avoided by the third year through information boards displaying lists of essential medicines. The audit’s public meetings improved infrastructure, addressing a problem with building and equipment that was frequently brought up in meetings.[115]

CASE STUDY

Community Monitoring Creates Epidemic Resilience in Sierra Leone

ACTION: In 2012, a project fostered community monitoring of government-run health clinics and provided non-financial incentives to clinic staff.

IMPACT: Patient satisfaction and clinic utilization increased. Additionally, community monitoring generated a 38% decrease in deaths of children under five. During the Ebola crisis of 2014, community-monitored clinics led to increased reporting of Ebola cases by 62% and significantly reduced Ebola-related deaths. Evidence suggests that community monitoring improved perceived quality of healthcare, encouraging patients to report Ebola symptoms and receive medical care.[116]

EDUCATION

- Social audits improve the education sector.

- An analysis of World Vision’s CVAs across twelve countries (Uganda, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Senegal, Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia, Kosovo, Armenia, Pakistan, Lebanon, and Romania) showed positive improvements in the health and education sectors. The study found an increase in student test scores, an 8–10% increase in student attendance, a 13% reduction in teacher absenteeism, and a 16% increase in communities likely to engage in collective action.[117]

- A study of the first social audit of education undertaken in India found that social audits improved student enrollment and teacher punctuality, increased the number of new schools, and decreased corporal punishment and non-payment of extra fees.[118]

- Community monitoring of the Philippine Department of Education’s bidding and delivery processes for textbooks helped to improve the quality of textbooks and reduce their cost.[119]

BUDGET ACCOUNTABILITY

- Community-driven social audits can reveal problems with supply and service provision.

- Findings from a social audit of sanitation and janitorial services in informal settlements in South Africa revealed gaps in the supply and maintenance of toilets—missing toilets, contractual violations by private providers responsible for cleaning toilets, damaged toilets, risks to residents using unstable toilets, and lack of transparency about waste disposal.[120]

- A study focusing on civic participation in Cape Town, South Africa found that social audit data often demonstrated significant gaps between the budgeted allocation for services and the services that actually existed. The government’s commitment to open data fueled participatory governance, public engagement, and activist agendas.[121]

COLLABORATION AND TRUST

- Social audits promote collaborative working environments and increase trust through direct involvement of participants.

- Social audits in Nepal build trust between primary healthcare providers and the communities they serve by giving people a space to voice concerns. This works especially well when combined with other dispute resolution mechanisms.[122]

- In Andhra Pradesh, India, a study of the state-initiated social audits found that villagers become more active in claiming government programs during social audits. During social audits, most workers raised grievances and engaged individually with auditors as well as collectively in the public forum, without fear. Eighty-five percent of workers said they had increased confidence to seek information from officials. The study also found that social audits increased state visibility, successfully detected and contained wage theft, and increased answerability of the state.[123]

- In reviewing the accountability effects of state-initiated social audits in Andhra Pradesh, India, a study found that social audits went beyond corruption and detected day-to-day maladministration such as caste and gender discrimination. Audits were a forum for positive feedback, and officials suggested that the public nature of the audits made them an effective monitoring mechanism because they encouraged people to speak.[124]

- A review of CARE’S Community Score Card (CSC) program, which spans five countries (Malawi, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Egypt), found that most projects with CSCs increased trust and openness between providers and community members. Additionally, CSCs reported changes in access to and utilization of services: increased institutional deliveries, easier access to voluntary counseling and testing, and respectful and responsive providers.[125]

CASE STUDY

State-Led Social Audits in India Reduce Corruption

ACTION: In Sikkim, India, social audits were implemented to review the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) rural work program. After seeing positive results, the format of the audits was adjusted and scaled to other regions.

IMPACT: Regular social audits decreased reported irregularities within the NREGA program. Social audits:

- Increased participation of wage workers who sought employment in NREGA;

- Increased the return of misappropriated funds;

- Created a “non-adversarial environment” and set a minimum participation limit (30% of job cardholders) to convene the public forum;

- Decreased absolute levels of corruption (e.g., the misappropriated funds compared to the sanctioned cost for work), suggesting the efficacy of social audits remains strong over multiple rounds;

- Closed the feedback loop with an exit conference of high level officials with authority to act on findings; and

- Adjusted the structure of the social audit teams to save costs and ensure effectiveness of the process.[126]

CASE STUDY

Citizen Voice & Action Audits Improve Public Services in Bangladesh

ACTION: The Nobo Jatra Program implemented CVA programming in the health, water, and sanitation, and agriculture sectors with the aim of improving citizen engagement and service provision.

IMPACT: Through the use of CVA, citizens gained confidence in voicing the demand for services. Officials appreciated citizen feedback on gaps in services and responded to 51% of demands for health clinics and water and sanitation, and 40% of demands for agriculture under agreed action plans. After CVA and by 2020, compliance monitoring standards increased in community clinics (88% of clinics targeted), and water and sanitation committees and union agriculture units (55% of units targeted). Finally, the CVA process has begun to “trickle up” to mid-and national-level actors, promoting interagency coordination and formal institutional accountability.[127]

Limits to the Evidence

- The scale of social audits is limited to targeted, localized problems. Many social audits do not present evidence either way on how they affect provincial, subnational, or national governments. Understanding whether, how, and when these types of interventions operate at scale is essential.

- Institutional knowledge is essential to successful social audits. Many social audits are dependent on third-party convenors and local groups who know decision-makers and can objectively facilitate access between the parties. Without these facilitators, the process is less likely to have a positive influence. Understanding this, it is important to think about how and when formal government-led interventions can make a difference.

- Quantitative evidence from diverse geographical and economic areas can strengthen the case for social audits. Most of the research available on social audits is qualitative, is concentrated on South Asia, and is not often peer-reviewed. This calls for an increase in quantitative and more geographically-diverse research, including in middle- and high-income countries, where the approach is growing in popularity.

“In order to serve the citizens of any city, you have to know what the citizens need, and there’s no better way to do that than actually talking to the citizens.”

Steve Potter, Member of the Austin Homelessness Advisory Committee, 2020.

Grievance Redress Mechanisms

This chapter is based on a background paper by Suchi Pande and Naomi Hossain developed to support the Skeptic’s Guide with guidance from the Accountability Research Center.

The Benefits of Grievance Redress Mechanisms

Grievance redress mechanisms (GRMs) in the public sector can powerfully supplement the justice system and improve governance and public service delivery. They can identify and tackle damaging practices, minimize harm on affected people, and avoid unjustified delays or cancellations of services and programs.[128]

Definitions

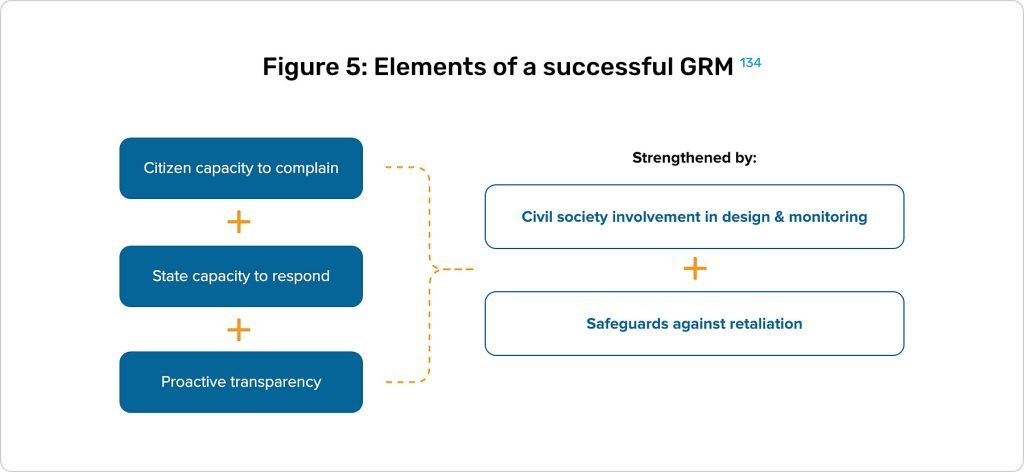

- Grievance redress mechanisms: Institutionalized, public sector processes that enable citizens to complain about and seek redress for services they should rightfully have received.[129] Government agencies create GRMs to encourage individuals to voice their concerns.[130] Elements of a successful GRM are:[131]

- Citizen capacity to complain: People should know their rights and what to expect from public programs. They should have institutional support to access benefits and to use complaint mechanisms to get a timely response without fear of reprisal.

- State capacity to respond: State actors need independence, authority, and resources to register, track, and resolve complaints and enforce decisions. State actors must be able to redirect or escalate complaints when they cannot handle them themselves, and they must be committed to maintaining the anonymity of complainants.

- Proactive transparency: GRMs must be proactively transparent about the nature and number of complaints, the rate of resolution, and the time taken to fully resolve them. Where complaints are dealt with in secrecy, there are few external pressures on government actors to resolve them. Proactive transparency is particularly crucial if GRMs are to achieve positive policy feedback, as it can highlight widespread or systematic problems within a sector that require transparency to rebuild institutional trust.

Experiences from GRM implementation in developing countries yield additional lessons learned. The following elements create strong GRMs:

- Civil society involvement in co-designing GRMs and in verifying that complaints are addressed;[132] and

- Including safeguards against retaliation like ensuring anonymity even when complaints are transferred between departments. Citizens might decrease their use and trust in GRMs if their use leads to retaliation against them. This retaliation can mean losing their beneficiary status or can escalate to even more serious consequences such as harassment and murder.[133]

Figure 5 highlights these elements.

GRMs in the public sector

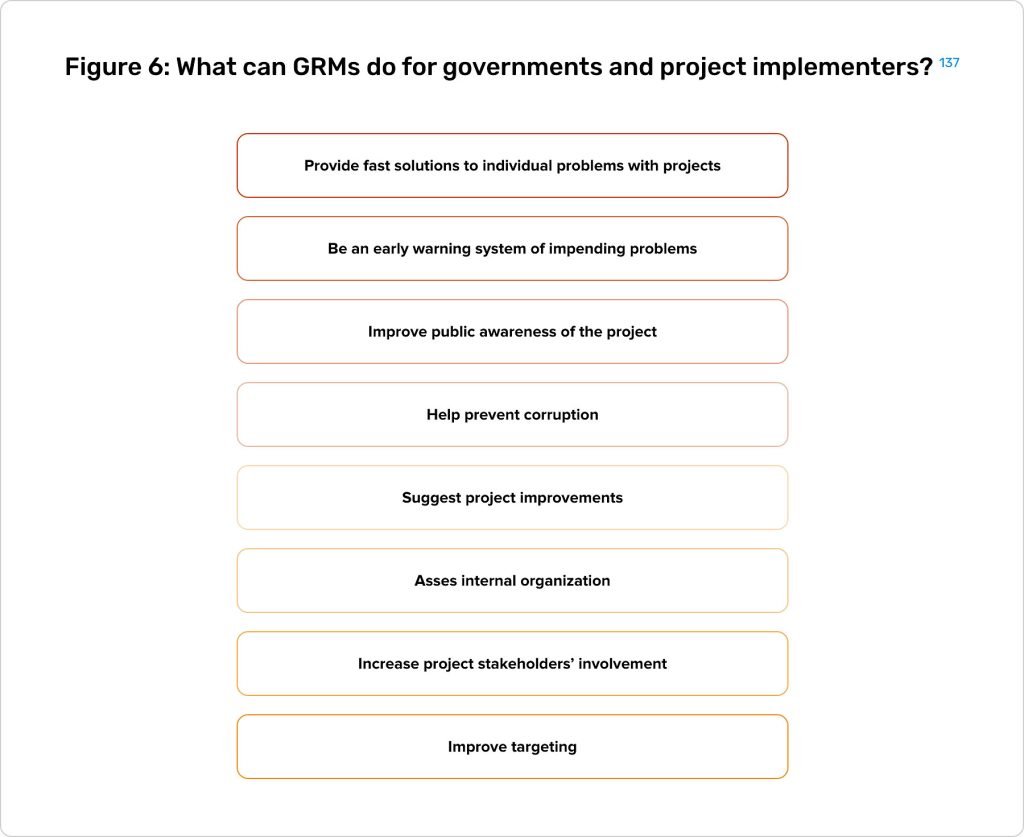

GRMs are increasingly widespread in different sectors. Development aid agencies such as the World Bank have increasingly included them in their lending operations since 2008 and, since 2018, the World Bank has made them mandatory in all investment project financing.[135] GRMs have also been implemented in the private sector, as they have proven to reduce “financial, construction, operational, reputational, and corporate risks.”[136] Experiences from these sectors have strengthened the case for GRMs. Figure 6 lists some of the benefits of private-sector GRMs that can transfer to the public sector.

To date, much of the research on GRMs has been about their use in public-private partnerships, such as megaprojects, or major private investments such as mining or petroleum operations. This section focuses on a growing trend: putting GRMs into the day-to-day operations of public-sector administration.

Social audits and GRMs complement each other. Social audits are a tool to monitor public service delivery, while GRMs are an avenue to voice complaints when governments are not delivering those services as they should. In a sense, social audits are a preventative measure whereas GRMs are reactive ones.

The Evidence

Here is what the evidence shows on how GRMs work in the public sector and how they can be designed and implemented to be more effective.[138]

EQUALITY AND SAFETY NETS

- GRMs help citizens in poverty benefit from public services. The Philippine flagship conditional cash transfer program, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (“4Ps”) included a mechanism for receiving and addressing complaints since its inception in 2007. This program targets the poorest population and provides households with a daily allowance that is conditional upon children attending school and regular health checkups. Through the program’s GRM, implementers have successfully been able to track and categorize the complaints they received. In 2017, the program reached a complaint resolution rate of 91%.[139]

- GRMs empower women. Beneficiaries of the Benazir Income Support Program in Pakistan claimed that being able to visit public offices to register their complaints about the program was itself an empowering experience for women who previously had no incentives to engage with public officials.[140]

- Intermediaries and facilitators can build trust and increase the usage of GRMs. While digital GRMs might help citizens report on government performance by bypassing the bureaucratic process,[141] these might not be the best solution for certain communities. Digital GRMs lack the personal approach that an intermediary or facilitator can give. Facilitators can build trust and guide citizens to voice their grievances. This is particularly important in communities that feel they have been treated unfairly by the state.[142]

- GRMs help people with disabilities participate in programs that they are entitled to. In Egypt, government-run GRMs were used to analyze complaints from people with disabilities who rightfully alleged to have been excluded from the Takaful and Karama unconditional cash transfers program. The GRMs helped staff identify the incorrect recording of disabilities affecting eligibility for the program. Of more than 270,000 complaints between 2018 and 2020, almost 100,000 complainants had their assessments revised so that they became eligible for the cash transfers.[143]

CITIZEN SATISFACTION

- GRMs help turn citizens’ grievances into satisfaction. In 2014, Kenya launched MajiVoice, an integrated system that receives complaints about water services face-to-face, through the phone, and online (although 97% of complaints are made in person or through the phone). It is monitored by the Water Services Regulatory Board, which ensures transparency and is empowered to take legal action against failures in service standards. During the first year of MajiVoice’s implementation, the number of complaints increased almost tenfold, the pace of redress constantly improved, and average turnaround times decreased by half. A 2017 survey of MajiVoice users found that almost half of them were satisfied or very satisfied with the experience and that 60% felt that their complaint was taken seriously by the water company.[144]

- Citizen monitoring through digital platforms can improve government staff performance. An urban municipal water provider in India improved their GRM with an online system that monitored staff performance based on citizen complaints. Since this digital component was added, users perceived “significant changes” in staff behavior.[145] Complaints were addressed in four days as opposed to the previous practice of not being addressed at all.[146]

Limits to the Evidence

- Evidence is limited to developing countries. Further lessons and evidence can be drawn from GRMs in middle- and high-income countries.

- Success of GRMs might be attributed to the initial motivation to implement them. While there are common elements across GRMs, the motivation from politicians and governments to implement them affects how they are designed and evaluated. For instance, when GRMs are mandated by law, they might be more ornamental than functional.[147] Thus, it is important that all stakeholders internalize and communicate the benefits of GRMs and implement them with purpose, beyond mere compliance.

- Public-sector GRMs are a common but understudied institutional practice. Given that policies and programs often require the implementation of GRMs, they have not been questioned or studied. In some contexts, there is no need to “build a case for” GRMs because they are already mandated.[148] However, further research would benefit the quality of GRMs.

- Further research is needed on the big-picture impacts of GRMs. Most literature on GRMs focuses on their internal efficiency rather than on how they affect service delivery and citizen-state relationships in the long term. Research tends to focus on improving consequences in response to service failures, rather than addressing the causes of service failures; the potential of policy feedback loops is not addressed. Additionally, there is more attention to the successful registration of complaints than on their resolution.[149]

- GRMs’ role is limited. Although they might identify and address problems, GRMs cannot compensate for poorly designed or implemented programs.[150] GRMs have been proven to be helpful with problems that have a rules-based solution, such as enrollment and registration errors or a delayed payment.[151] They are rarely suited to solve other matters such as a person’s ineligibility for a program. Citizens who are ineligible but believe they deserve the benefit might submit a claim, and they might end up even more disappointed when the agency receiving the claim cannot address their concern.[152]

- Digitalization of GRMs might not work for all populations. Intermediaries are still important to facilitate access to GRMs in populations who feel they have been treated unfairly.[153]

- The gendered effects of GRM access call for CSO involvement. Evidence from Indonesia, Kenya, and Ethiopia point toward greater usage of GRMs among men with college degrees.[154] Women and other underserved groups are less likely to complain and benefit from civic or organizational support in registering and following up on complaints.[155] Thus, it is important to protect and foster civil society organizations’ role in acting as intermediaries with citizens.

“The provision of public services is a key component of the social contract between governments and citizens, and an area where open government reform is likely to have the most meaning and impact for citizens at the local level.”

Isaac Aidoo, OGP Government Point of Contact for Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana, 2020

Civic Space

This chapter is based on a background paper by Peter Noorlander developed to support the Skeptic’s Guide with guidance from the American Bar Association’s Rule of Law Initiative and Center for Human Rights.

The Benefits of Protecting Civic Space and Democratic Freedoms

Civic space and democratic freedoms are the cornerstone of an open and democratic society.[1] An open civic space allows citizens and civil society organizations to freely and independently associate, express themselves, participate in public life, and seek information from the state.[2]

Definitions

- Civic space and democratic freedoms. For the purposes of this chapter, this encompasses the fundamental freedoms of

- expression,[3]

- assembly, and

- association.

These rights are protected in articles 19 and 20 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as in Articles 19, 21, and 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the main international binding human rights treaty ratified by 173 countries.

Some organizations and experts in the field define civic space more broadly, to include interactions between the government and civil society, as well as the right to seek information. This chapter, however, will focus on the three rights listed in the definition. They are also often called “democratic freedoms,” “civic freedoms,” “civic rights,” or “civil liberties.” This review will use these terms interchangeably.

- Media freedom: The ability of journalists to report freely on matters of public interest.[4] It is a principle within freedom of expression that, as the evidence in this chapter shows, is associated with positive societal benefits.

Evidence

The following sections present evidence of the positive impact protecting civic space has on society as well as the deleterious effects of measures that threaten or restrict any of the freedoms within it.[5]

Economic Growth

- Improving democratic freedoms is closely associated with faster growth. Countries that move from 0 to 1 on the V-Dem Civil Liberties Index increase their per capita GDP by an average of 1.3 percent over a period of five years.[6] This index includes indicators such as freedom of speech, media censorship, harassment of journalists, and civil society repression, covering data from 1900–2016 in 201 countries.

Social Inclusion

- Less civic space means that people with less power – the poor, disadvantaged women, rural communities, and indigenous groups–remain powerless. This results in more inequality. A 2019 report covering Bangladesh, Brazil, Cambodia, China, Colombia, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Myanmar/Burma, Nepal, Russia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe concluded that restrictions on civic space are likely to reverse progress toward reducing inequality, ensuring inclusion, and improving sustainability.[7] This is because closing civic space, with actions such as threatening, criminalizing, or being violent against civil society actors to delegitimize and stigmatize them, makes it difficult or impossible for marginalized groups to voice their concerns or to organize and empower their members.[8]

- As civic space narrows, the most marginalized and disempowered groups face a growing risk of being left behind. A study based on research in Brazil, Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe found that legal restrictions to Civil Society Organizations’ (CSO) operations as well as intimidation, criminalization, and surveillance limit their ability to do the following:

- influence and critique policy to hold government accountable, and

- provide services to people facing poverty or hunger.

This, in turn, obstructs civil society efforts to reach marginalized groups, widening their exclusion from policy processes and services.[9]This is especially true when there are penalties for helping groups identified as criminal, such as drug addicts, sex workers, members of the LGBTQ+ community,[10] asylum seekers, or migrants, to name a few.[11]

- Restricting online civic space limits inclusive development. A study across ten African countries found that government measures such as internet shutdowns, the taking down of material, and surveillance make it impossible to reach the inclusive, responsive, participatory, and representative governance that SDG 16 aims at. Specifically, the report finds that digital surveillance, disinformation, internet shutdowns, anti-civil society legislation, and arrests for online speech serve to intimidate independent organizations and often amplify social cleavages, resulting in further exclusion.[12]

- Local-level CSOs ensure inclusion in development. Nepal underwent a political transition in 2006 after ten years of civil war, the development of a new constitution, and rehabilitation after an earthquake in 2015. A case study on the role of civil society organizations during this period highlights that CSOs at the local level are particularly vital for ensuring inclusion.[13] The study explains that civil society actors at the national level have played an important role in defining political and civil rights in the past three decades, but local and grassroots organizations are perceived to have higher legitimacy and independence from donor-driven agendas and national-level politics. This legitimacy fosters greater participation from communities at the local level and castes that might have been neglected after a conflict and increases the inclusion of their perspectives into decision-making.

Political Stability

- The media contributes to political stability by exposing constituents to different viewpoints. A case study conducted during Uganda’s 2016 parliamentary elections demonstrated that voters who were exposed to electoral messages from multiple candidates were less likely to vote for ruling-party candidates.[14] This strengthens democratic values, such as electoral competition, reducing the possibility of a dominant-party regime.

- Free debate in media is associated with a more active citizenry. A study across seven Asian and African countries with data from more than 23,000 respondents found increased political participation for the audiences of political debate programs.[15] See the “Case Study: Media Fosters Political Participation in Asian and African Countries” for more details.

- Crackdowns on the press precede political democratic breakdown:

- Following an in-country investigation in Turkey, Freedom House analyzed that pressuring the independent media has been part of an overall crackdown on democratic values in the country.[16]