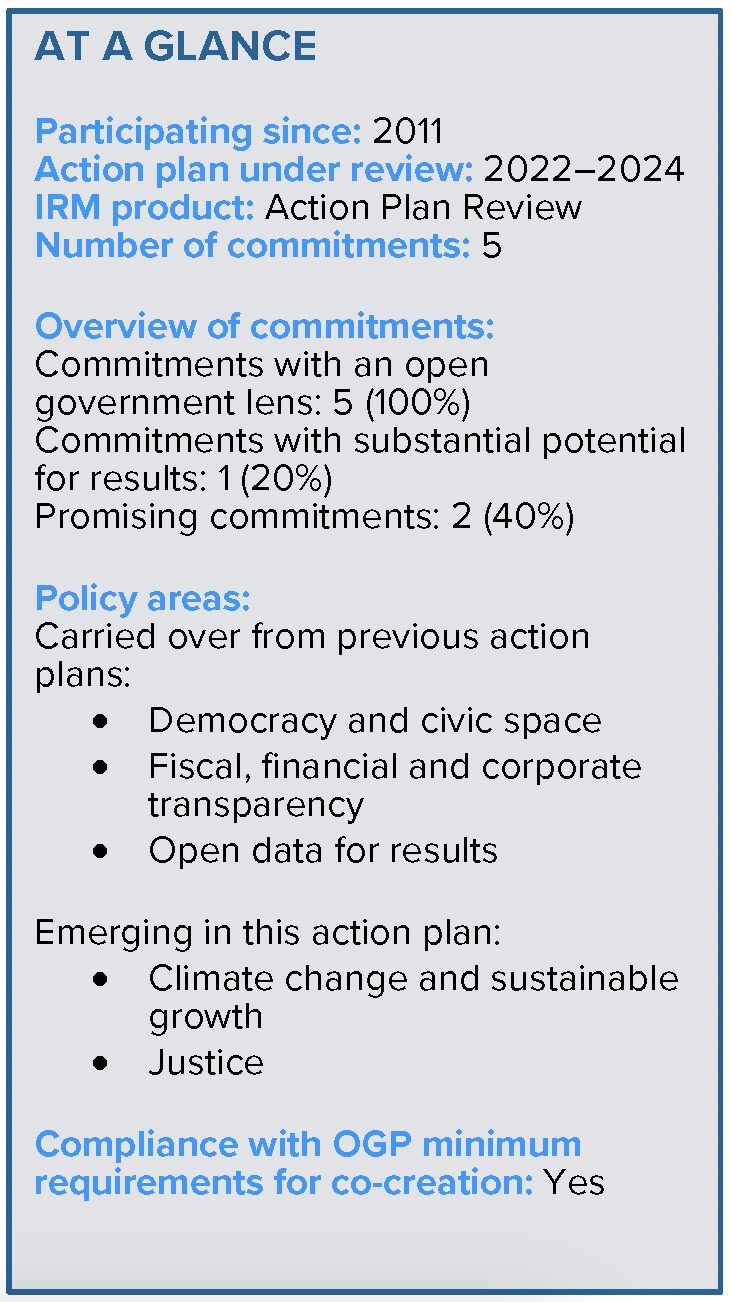

Canada Action Plan Review 2022-2024

- Action Plan: Canada Action Plan 2022-2024

- Dates Under Review: 2022-2024

- Report Publication Year: 2024

The 2022–2024 National Action PlanAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... (NAP) largely carries forward and supplements elements of Canada’s 2018–2021 NAP, introducing commitments in two new policy areas. Despite advancing relatively positive activities and initiatives, the potential for results of most commitments and milestones is tempered by the absence of a strong, coherent logic model linking actions to meaningful changes in the problems identified. The plan would benefit from setting out more focused commitments, targeting both current issues facing Canadians and requisite structural improvements to reinforce government capacity, policies, and culture toward openness.

Canada’s 2022–2024 NAP is structured around five themes with associated commitments. Three themes carry forward and supplement commitments from the 2018–2021 NAP. Two introduce commitments in new policy areas. The five themes are: climate change and sustainable growth (new area); democracy and civic space; fiscal, financial, and corporate transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More; justiceTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi... (new area); and open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici... for results. The commitments associated with each theme set out broad lines of action that, despite including specific activities, are vague in identifying both the specific problem being addressed and the outcomes expected from implementing these activities.

The five themes include 19 milestones and 106 activities identified as indicators of success. As written in the action plan, the stated objectives and proposed actions under each of the five themes are clear and include objectively verifiable activities. In most instances, however, the link between the proposed activities and desired outcome(s) is ambiguous.

There are two key areas in which the action plan might improve. First, the plan lacks a strong, coherent logic model connecting the proposed activities to substantive changes in the problems identified. With few exceptions, the proposed activities constitute relatively positive, but not particularly ambitious or meaningful efforts at addressing the issues set out in the action plan. Second, the milestones and proposed metrics provided in the 2022–2024 action plan should be more specific and include both baselines and measurable indicators – whether quantitative, qualitative, or some combination thereof – for assessing whether proposed activities lead to successful outputs and/or outcomes.

Canada’s previous action plans similarly lacked adequate indicators for measuring progress toward desired goals. Specifically, the IRM has consistently identified the validity of the proposed success indicators (i.e., do they actually measure/reflect what they claim to measure?) as needing improvement. As Goodhart’s law states, “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Echoing Provision 5 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government,[1] in developing indicators for measuring progress toward opening government it is useful to: (i) first establish starting, or reference, points (i.e., baselines) against which progress toward stated objectives can be assessed; and (ii) develop or identify appropriate indicators to be used to measure against the baseline in assessing whether (and what) progress is being made.[2]

In terms of the strengths and limitations of the action plan development process, and as noted in the preamble of the 2022-2024 NAP, both civil society and and government members of the Multi-Stakeholder Forum (MSF) expressed some dissatisfaction.[3] This dissatisfaction appears to have been linked, in part, to the fact that both sides are learning by doing. The principal strength of the process was back-and-forth dialogue that developed in tandem with developing the action plan. As per both the civil society and government members of the MSF with whom the IRM Researcher met, a distinguishing feature of this dialogue, which arose at the behest of the MSF’s civil society members, was the government’s reporting back to civil society members about the progress being made on their inputs and requests.

One limitation of the plan development was the absence of orientation training for both government and CSO members of the MSF. The government representatives with whom the IRM researcher met felt such training could assist CSO members in better understanding the intricacies of both the federal government’s internal operations, and the time and resources needed to implement changes. The CSO members likewise thought it would be useful to train government representatives—both within and outside of the MSF—on how to more effectively engage with civil society representatives.

A related limitation pertains to the governance of the MSF. Specifically, the need to formalize how the two parties collaborate. There is unresolved tension between the notion that government and civil society MSF members are working on the same team toward a common goal versus the idea that they are adversaries who must find ways to collaborate for a common cause. Government representatives are seemingly more sympathetic to the former perspective. However, civil society members seemingly favor the latter, lest the MSF be seen as a body for legitimating government actions. This matter requires further attention as it has direct implications for the perceived legitimacy of the MSF among members of Canadian civil society.

As noted in the IRM’s assessments of each of Canada’s four previous NAPs, the misalignment between the Government of Canada’s budget process and the OGP action plan cycles is an obstacle to co-creating ambitious reforms. This is also the case with the fifth NAP. One of the five associated commitments, Commitment 3, and a number of milestones and indicators of success were already near completion or even completed when the plan was launched in September 2022.[4] For example, Milestone 3.1 was actualized six months after the launch of the plan, in March 2023, when the Government of Canada tabled new legislation to create a beneficial ownership registry to “make public some information regarding beneficial owners of federal corporations.”[5]

Milestone 3.1 (implement public and searchable beneficial ownershipDisclosing beneficial owners — those who ultimately control or profit from a business — is essential for combating corruption, stemming illicit financial flows, and fighting tax evasion. Technical... More registry) and Milestone 4.5 (open government at the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)) represent the most promising steps forward in terms of their potential for opening government and generating binding and institutionalized changes across government and Canadian society more broadly.

The associated commitments of the other four themes and their activities are laudable. There is new information about Canadian society being gathered, analyzed, and disclosed as well as efforts to engage with a variety of public groups. However, the absence of a strong, coherent logic model, as described above, combined with the lack of baselines and adequate indicators with which to measure progress impedes assessments of whether these activities meaningfully enhance practices, policies, or institutions that govern a policy area, public sector, or the relationship between citizens and state. Many of the milestones and success indicators set out in the NAP appear to be informed by data solutionism. The IRM Researcher notes that the underlying question informing the development and design of commitments and their associated activities should be “What are the conditions under which open government can be harnessed to achieve desired outcomes?” rather than “How can open government and open data be harnessed to achieve desired outcomes?”

Promising Commitments in Canada 2022–2024 Action Plan

The following review looks at two (2) commitments that the IRM identified as having the potential to realize the most promising results. Promising commitments address a policy area that is important to stakeholders or the national context. They must be verifiable, have a relevant open government lens, and have modest or substantial potential for results. This review also provides an analysis of challenges, opportunities, and recommendations to contribute to the learning and implementation process of this action plan.

Table 1. Promising commitments

| Promising Commitments |

| CommitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 3: Fiscal, financial and corporate transparency |

| Commitment 4: Justice |

[1] Provision 5 recommends that adherents to the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government,

develop and implement monitoring, evaluation and learning mechanisms for open government strategies and initiatives by:

(i) Identifying institutional actors to be in charge of collecting and disseminating up-to-date and reliable information and data in an open format;

(ii) Developing comparable indicators to measure processes, outputs, outcomes, and impact in collaboration with stakeholders; and

(iii) Fostering a culture of monitoring, evaluation and learning among public officials by increasing their capacity to regularly conduct exercises for these purposes in collaboration with relevant stakeholders.

See, OECD “Recommendation of the Council on Open Government” (OECD, 2017), https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438. See also, OECD, Open Government Scan of Canada: Designing and Implementing an Open Government Strategy, OECD Public Governance Reviews, (OECD Publishing, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1787/1290a7ef-en.

[2] For a concise overview of baselines, see: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Cross Societies. “Basline Basics” (2013), https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/Baseline_Basics_2013.pdf. See also, UN Women, “Baseline studies,” (Virtual Knowledge Centre to End Violence against Woment and Girls, 2011), https://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/959-baseline-studies.html.

[3] Open Government Partnership, “Canada Action Plan 2022–2024” (22 Septbember 2022), https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/canada-action-plan-2022-2024/

[4] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, “Canada launches 2022–24 National Action Plan on Open Government” (Government of Canada, 22 Sep. 2022), https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/news/2022/09/canada-launches-202224-national-action-plan-on-open-government.html.

[5] Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “Government of Canada tables new legislation to create a beneficial ownership registry” (Government of Canada, 22 Mar. 2023), https://www.canada.ca/en/innovation-science-economic-development/news/2023/03/government-of-canada-tables-new-legislation-to-create-a-beneficial-ownership-registry.html.

Leave a Reply