Finland Results Report 2019-2023

- Action Plan: Finland Action Plan 2019-2023

- Dates Under Review: 2019-2023

- Report Publication Year: 2024

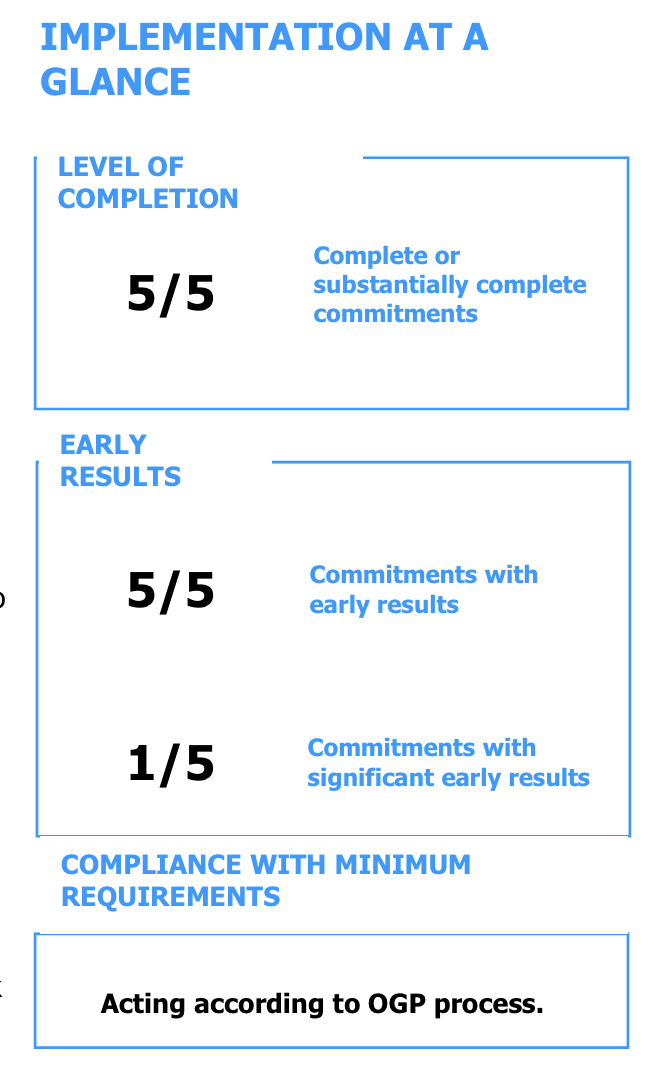

Finland’s fourth OGP action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... was the country’s first to span four years (2019—2023). Finland completed most commitments despite the COVID-19 pandemic and shift of national priorities following Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine. The action plan resulted in the adoption of a mandatory lobbyingLobbying transparency allows the public to ensure that there is diversity of participation and contribution to public decision-making. Technical specifications: Policies and actions affecting lobbying... register and institutionalization of national dialogues as a new public participationGiving citizens opportunities to provide input into government decision-making leads to more effective governance, improved public service delivery, and more equitable outcomes. Technical specificatio... method. Civil society played an active role in guiding and co-implementing commitments.

Early ResultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More

Finland’s fourth action plan originally contained four commitments, with a fifth commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... added later. One commitment (3) yielded significant early results, while four achieved moderate early results in advancing open government. Commitment 3 (TransparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More Register) was highlighted as noteworthy in the IRM Design Report and significantly advanced lobbying transparency in Finland. The government added Commitment 5 (national dialogues) to the action plan following a mid-term self-assessment. This commitment also produced strong early results by establishing a regular practice in the government of holding dialogues with citizens and building a multi-stakeholder network and governance structure to ensure the continuation of the practice.

CompletionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More

The action plan focused on promoting sustainable open government practices through public officials’ capacity-building and networking. It also sought to advance lobbying transparency, public participation, open data, and ethical use of Artificial Intelligence (AI). All commitments were fully or substantially completed, with relatively minor deviations from the original work plan and timeline. The Ministry of Finance (MoF) followed through both with commitments where the ministry had the sole responsibility for implementation (Commitment 2 – open government strategy) and those implemented in collaboration with civil society (Commitment 5 – national dialogues). The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) was responsible for Commitment 3 (transparency register). Although this commitment was the most complicated, the MoJ completed it on time thanks to extensive preparatory work carried out years before the start of the action plan.[1]

Participation and Co-Creation

The Governance Policy Unit at the MoF continues to coordinate the OGP process in Finland. Two multi-stakeholder advisory bodies oversee the process: the Open Government Working Group (avoimen hallinnon työryhmä), which is responsible for participating in the co-creation and supporting the implementation of OGP commitments[2] and the government’s Civil Society Advisory Board (kansalaisyhteiskuntapoliitikaan neuvottelukunta – KANE[3]), which has a broader mandate of advising the government’s civil society policies. Following a highly collaborative co-creation processCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders (e.g., citizens, academics, private sector) is at the heart of the OGP process. Participating governments must ensure that a dive..., civil society organizations (CSOs) also had an active role in implementing the commitments. CSOs had strong representation in the steering groups coordinating the implementation of CSO academies (Commitment 1) and national dialogues (Commitment 5). As standard practice, Finnish government institutions conducted online public consultations on all major policy initiatives. For the transparency register (Commitment 3), amendments to the Openness Act (Commitment 1), and the renewal of the open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici... policy framework (Commitment 4), the government also maintained regular dialogue with CSOs throughout commitment implementation by involving civil society in the advisory bodies established to guide commitment implementation.

Implementation in context

Several unexpected events shaped the open government context during the action plan term. First, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that information on public health measures was not readily available for users of easy language, such as people with migrant backgrounds and people with developmental disabilities.[4] The government discovered that many migrants who did not have a good command of Finnish had fallen victim to false information on pandemic-related mobility restrictions due to lack of understandable government-provided information.[5] This underlined the urgency of building public administration’s capacity in easy language, which was part of Commitment 1. Government institutions thereafter strengthened their efforts to provide timely information on the crisis in easy language.[6] The government also launched the Lockdown Dialogues, a series of discussions bringing together participants from diverse sectors to discuss their life experiences during the pandemic.[7] The success of these dialogues in fostering participation and mutual understanding encouraged the government to introduce Commitment 5 to the action plan to establish a model for dialogues at the national level. At the same time, the pandemic delayed the implementation of certain milestones, such as developing guidelines for the ethical use of Artificial Intelligence (Commitment 4)[8] and creating an online version of the Openness Game (part of Commitment 1).[9]

Moreover, Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine significantly changed the security situation in Finland, spurring Finland to join NATO at an unprecedented speed[10] and fostering political support to the open government agenda to fight undemocratic tendencies and prevent the polarization of society.[11] The influx of refugees from Ukraine resulting from the invasion also reinforced the need to provide government information in easy-to-understand language.[12]

Table of Contents

Section I: Key Observations. 1

Section II: Implementation and Early Results. 4

Section III. Participation and Co-Creation. 13

Section IV. Methodology and IRM Indicators. 16

Key Observations

Finland was the first OGP member to introduce a four-year action plan. Finland’s positive experience with this format encouraged the government to continue with four-year action plans (the fifth action plan runs from 2023-2027). Thanks to the government’s strong baseline in open government and deeply institutionalized collaboration with civil society, the government made use of open government approaches to help society cope with unexpected crises during the action plan term. One of the key achievements of the action plan – the establishment of a mandatory lobbying transparency register – was greatly facilitated by a participatory process.

Observation 1: The four-year action plan term enabled the government to focus on strong implementation, while maintaining flexibility.

The Ministry of Finance (MoF) believes that adopting a four-year action plan term enabled the government to focus more energy on commitment implementation, rather than planning another action plan every other year.[13] This resulted in a high completion level of the commitments. According to the MoF, the longer action plan term also allowed the government to conduct a more thorough co-creation process. At the same time, Finland’s experience demonstrated that a four-year action plan can provide flexibility to incorporate new priorities and react to changes in the context, as the government added a fifth commitment to the action plan after the mid-term self-assessment.[14] Thanks to the positive experience with the fourth action plan, the government decided to continue implementing four-year action plans. However, the MoF acknowledges that it is not clear to what extent the action plan results were influenced by the longer action plan term as opposed to the extraordinary factors (the COVID-19 crisis and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine) that affected the open government context during implementation.

Observation 2: Crises and challenges opened new avenues for open government reforms.

The COVID-19 pandemic was not only a challenge but also an opportunity for open government in Finland, thanks to the government’s will and capacity to quickly respond to the crisis. As the Finnish government and its civil society partners were interested in alleviating citizens’ anxiety at times of significant disruptions in society and economy, they came up with the innovative concept of Lockdown Dialogues to engage people from all walks of life to share experiences and reflections of life during the pandemic.[15] The dialogues built on the “Timeout” approach – a method for constructive and creative citizen engagement, which the public think tank Sitra had started developing in 2016.[16] As the method was relatively easy to implement, anyone interested was invited to organize dialogues. During 2020–2021, more than 100 organizers engaged 2,130 participants in the dialogues.[17] The positive societal reception of the Lockdown Dialogues spurred the inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More of Commitment 5 into the fourth action plan in the middle of the action plan term to develop a model for regular national dialogues. Thanks to this commitment, the national dialogue approach was easily at hand in 2022 to respond to another crisis – the changed security situation following Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine, when citizens were invited to the Democracy Defense dialogues to discuss ways of protecting democratic societies from internal and external threats.

Observation 3: Large-scale public participation initiatives benefited from multi-stakeholder governance mechanisms.

Much of the success of Commitment 5 (national dialogues) related to its reliance on an expansive multi-stakeholder network of dialogue organizers and a steering mechanism (core operational group) that involves central and local public authorities as well as CSOs. As a result of the fourth action plan, a network of about 60 organizations and activists regularly organize national dialogues, in addition to a looser network of organizations that have organized at least one dialogue.[18] Membership in the regular organizers’ network involves an obligation to conduct at least two dialogue events per year (two rounds of national dialogues are held each year – one in spring and one in fall). The core operational group, comprising seven public and non-governmental organizers, coordinates the selection of dialogue topics, synthesis of results and training of dialogue organizers, while the dialogues themselves are implemented by a broad network of organizations.[19] This model enables the government to share the burden of organizing citizen engagement, foster a broad sense of ownership of the dialogue process, and reach stakeholders and communities they may not be able to access on their own.

Observation 4: Transparent and inclusive processes helped implement ambitious and complex commitments.

One of the action plan’s most notable outcomes was the establishment of a transparency register to collect and publish data on lobbying targeted at the parliament and ministries. The development of the register, along with the legal and governance framework, was a long and complex process which involved a variety of stakeholders, including members of parliament, public officials, civil society and interest groups, and independent institutions such as the National Audit Office of Finland. As the commitment coordinator, the Ministry of Justice sought a broad-based agreement on the content and regulations of the register to support future compliance with the reporting rules.[20] The ministry led an inclusive development process engaging stakeholders through a variety of methods such as a parliamentary steering group and a multi-stakeholder working group who guided the process, conducting online surveys, public consultations, and stakeholder workshops, and commissioning research from universities to support evidence-based decisions.[21] The process was highly transparent – the composition of the working group, lists of involved stakeholders, and meeting memos were published on the Ministry of Justice’s website throughout implementation.[22] This approach helped ensure support from both coalition and opposition parties, which was crucial for the adoption of the new regulation.[23]

[1] Niklas Wilhelmsson (Ministry of JusticeTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi...), interview by the IRM, 13 February 2024.

[2] Ministry of Finance, Open Government Working Group, Avoimen hallinnon työryhmä 2019-2023, https://vm.fi/hanke?tunnus=VM153:00/2019

[3] Ministry of Justice, Advisory Board for Civil Society Policy KANE, Kansalaisyhteiskuntapolitiikan neuvottelukunta KANE https://oikeusministerio.fi/kane

[4] Open Government Partnership, Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM): Finland Design Report 2019–2023, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/finland-design-report-2019-2023/

[5] Katju Holkeri (Ministry of Finance), interview by the IRM, 21 February 2024.

[6] See, for example, Pipsa Lotta Marjamäki, Miten Kelan koronaviestinnässä on huomioitu selkeys ja selkokieli? 13 October 2020, https://www.kotus.fi/files/8793/5_Marjamaki_Kela_Diat_Selkean_kielen_paiva.pdf

[7] Elina Henttonen, Lockdown Dialogues: Crisis experiences and model for national dialogue, Sitra Studies 213, 2022, https://www.sitra.fi/en/publications/lockdown-dialogues/

[8] Open Government Partnership, Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM): Finland Design Report 2019–2023, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/finland-design-report-2019-2023/

[9] Katju Holkeri (Ministry of Finance), interview by the IRM, 21 February 2024.

[10] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Relations with Finland, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49594.htm

[11] Katju Holkeri (Ministry of Finance), interview by the IRM, 21 February 2024.

[12] Leealaura Leskelä (Selkokeskus), interiew by the IRM, 11 March 2024.

[13] Katju Holkeri (Ministry of Finance), interview by the IRM, 21 February 2024.

[14] Open Government Partnership, Finland Mid-Term Self-Assessment 2019–2023, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/finland-mid-term-self-assessment-2019-2023/

[15] Elina Henttonen, Lockdown Dialogues: Crisis experiences and model for national dialogue, Sitra Studies 213, 2022, https://www.sitra.fi/en/publications/lockdown-dialogues/

[16] Elina Henttonen, Lockdown Dialogues: Crisis experiences and model for national dialogue, Sitra Studies 213, 2022, https://www.sitra.fi/en/publications/lockdown-dialogues/

[17] Elina Henttonen, Lockdown Dialogues: Crisis experiences and model for national dialogue, Sitra Studies 213, 2022, https://www.sitra.fi/en/publications/lockdown-dialogues/

[18] National Dialogues, Actors in National Dialogues, https://kansallisetdialogit.fi/en/about-national-dialogues/actors-in-national-dialogues/

[19] National Dialogues, Actors in National Dialogues, https://kansallisetdialogit.fi/en/about-national-dialogues/actors-in-national-dialogues/

[20] Niklas Wilhelmsson (Ministry of Justice), interview by the IRM, 13 February 2024.

[21] Ministry of Justice, Transparency register, Avoimuusrekisteri: Säädösvalmistelu (OM033:00/2019), https://valtioneuvosto.fi/hanke?tunnus=OM033:00/2019

[22] Ministry of Justice, Transparency register, Avoimuusrekisteri: Säädösvalmistelu (OM033:00/2019), https://valtioneuvosto.fi/hanke?tunnus=OM033:00/2019

[23] Niklas Wilhelmsson (Ministry of Justice), interview by the IRM, 13 February 2024.

Leave a Reply