Implementing SDG16+ – Introduction

Implementación de SDG16 + - Introducción

July 2019

The challenge of building peaceful, just and inclusive societies is at the heart of the Sustainable Development GoalsOGP countries are experimenting with open government innovations to accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 16+ which includes peaceful, just and inclusive societies... (SDGs). These global goals, agreed at the United Nations by all countries in 2015, are designed to provide a roadmap for a better world by 2030. The Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More (OGP) can be a vital partner to achieve these goals.

Four years since the SDGs were agreed, there is widespread concern that implementation is so badly off-track for most targets that a dramatic shift in action will be needed to make significant progress by 2030. It is vital that 2019 is a year where people are inspired to take more ambitious action and commit to making the 2020s a decade of delivery.

Open government can be a strategic tool to help with implementation across the 17 SDGs. Government is better when it is transparent about its activities and with its data, when it proactively encourages public participationGiving citizens opportunities to provide input into government decision-making leads to more effective governance, improved public service delivery, and more equitable outcomes. Technical specificatio..., when it is responsive to citizen demands, and when it is prepared to be held accountable for successes and failures. Within OGP, countries are experimenting with open government innovations that could help accelerate progress on the global goals. These include a range of innovations that give citizens a greater say over how they are governed: whether it be how public services in water, health and educationAccountability within the public education system is key to improving outcomes and attainment, and accountability is nearly impossible without transparent policies and opportunities for participation ... are provided, where and how infrastructure projects are built, or how budgets are allocated.

Since OGP was founded in 2011, there have been almost 4,000 of these open government commitments from the 79 member countries, and an increasing number of local government participants. This briefing paper looks at some of the most relevant examples. It spotlights innovations across Goal 16+, the cluster of SDG targets that seek to achieve peaceful, just and inclusive societies, and accountable institutions. These are by no means an exhaustive list of examples of relevant open government reforms happening in OGP, but they are designed to showcase the potential of countries using their membership to more proactively link their commitments at the global level to national implementation. It includes work in South Africa to make budgetary information more accessible and participatory, in Colombia to make the legal system more accessible to citizens, in Sri Lanka to expand on access to information and in the UK to reduce opportunities for money laundering and corruption.

OGP’s mechanism is well suited to be the link between global commitments and national implementation because of its unique design elements. OGP members are required to submit concrete commitments every two years that are co-created between government reformers and civil society organizations. The discussions take place in an OGP forum, typically co-chaired by a government minister and a civil society leader, and are designed to be open to inputs from citizens as well as organized non-governmental organizations. Every year, an independent assessment of progress is conducted by OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism. These reports are public, and provide a vital learning and accountability tool that ensures progress is tracked and OGP is not a talking shop.

The examples in this briefing paper show that even on the toughest SDG targets, progress is possible and that innovations are taking place in OGP embers hat can be adapted and adopted by other countries. However, these examples are too few and far between. Strengthening the link between OGP and the SDGs could be a helpful way to accelerate the use of open government as a tool to deliver on priorities for governments and citizens at two levels.

First, OGP members should consider their biannual open government action plans as tools for committing to reforms that help the country meet their SDG targets. This was first outlined in the 2015 OGP Declaration on the SDGs that was agreed at the Mexico Global Summit, and is already underway in some OGP countries. In places where the link has been established governments could include it in their Voluntary National Review which for example the UK has done in 2019, and ensure that the relevant Ministry leading on SDG coordination has a seat at the table in their OGP forum. There may also be opportunities to make progress on open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici... and data management reforms that help SDG monitoring, so that better decisions can be made on where to allocate resources to meet the goals. The OGP forum can also bring in more diverse civil society voices working across policy areas reflected in the SDGs.

Second, OGP can incubate new open government norms that will help deliver progress on the SDGs. For example, on anti-corruption over 70 OGP members have commitments on open contractingA transparent procurement process, known as open contracting, increases competition, improves public service delivery, and ensures governments better value for their money. Technical specifications: C... More and public procurementTransparency in the procurement process can help combat corruption and waste that plagues a significant portion of public procurement budgets globally. Technical specifications: Commitments that aim t... More, helping governments save money, reducing state capture by well connected elites and increasing access to government business for small and medium owned enterprises. Open contracting is an example of a new open government norm that could help countries improve on basic service delivery for health, education and water provision, supporting progress across many of the SDGs if well implemented. Similar new norms are emerging on open budgets, access to information, ending anonymous companies and giving citizen’s options to provide feedback on public services.

This briefing paper shows that it is possible to achieve results, even in difficult circumstances and on challenging goals, by working together with reformers in and out of government, and having a strong focus on accountability. If the 2020s are really to be a decade of delivery for the SDGs, a stronger partnership with the open government community will be essential. OGP’s focus on national implementation, cross-country learning, and incubating new policy norms that could help make progress across the SDGs means there is potential for far more strategic collaboration in future.

The SDG16+ Framework

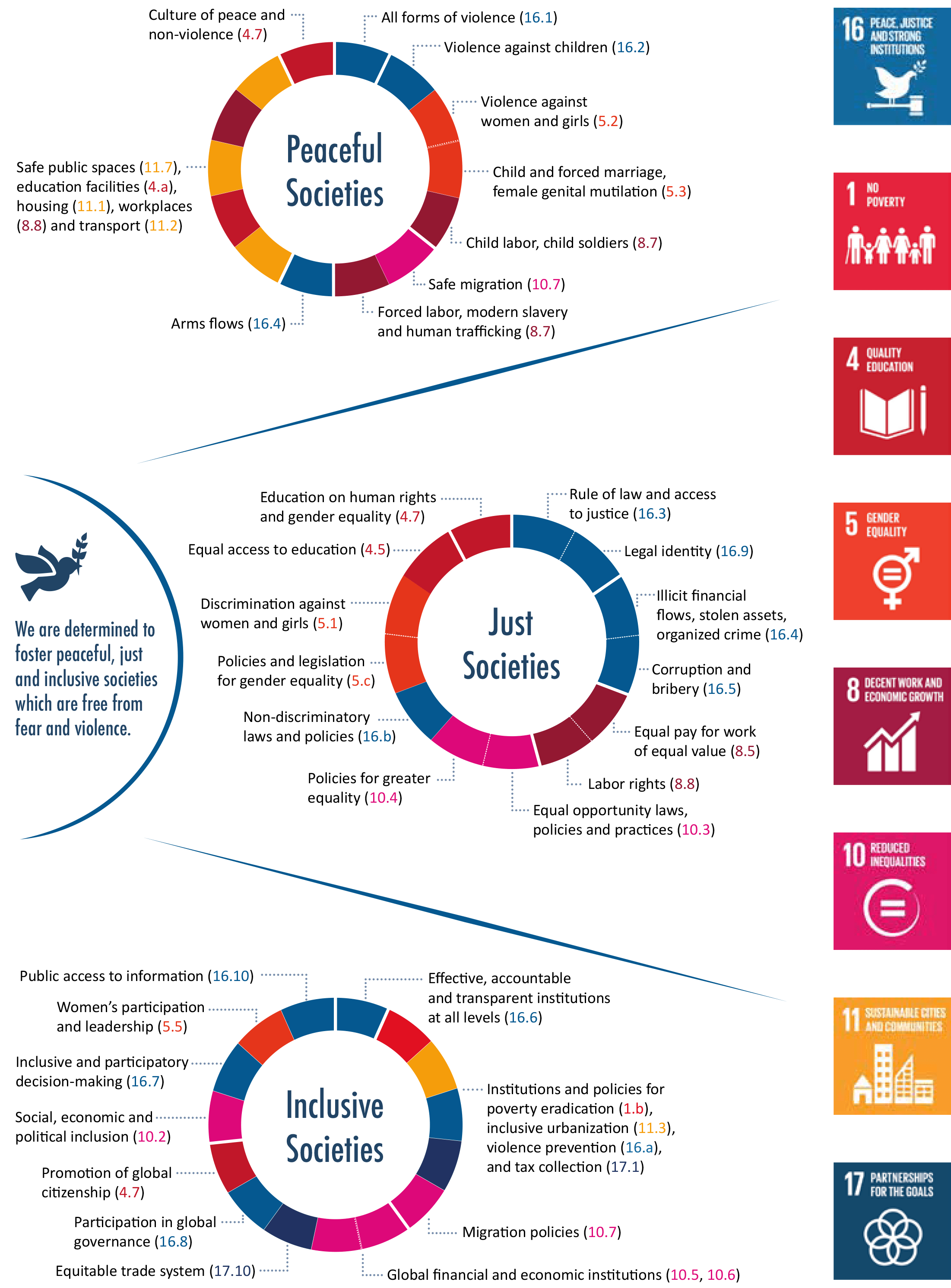

This briefing paper uses the SDG16+ framework established by the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies, which aims to ensure SDG 16 is not addressed in isolation from other relevant goals and emphasizes the strong interlinkages between different SDG targets. [1]

Many OGP members have made open government commitments relevant to the SDG16+ framework. This briefing paper looks at a selection of those commitments across a range of themes, including anti-corruption, access to justiceAccessible justice systems – both formal and informal – ensure that individuals and communities with legal needs know where to go for help, obtain the help they need, and move through a system tha... More, inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More, access to information and genderOGP participating governments are bringing gender perspectives to popular policy areas, ensuring diversity in participatory processes, and specifically targeting gender gaps in policies to address gov... More equality.

OGP action plans are also being used to advance reforms that help achieve a number of other global goals, including those related to improving basic public services on health, education and water. Those are not addressed in this briefing paper, but open government approaches are a powerful tool to make progress across the 17 goals. Approximately 30 national and six local OGP members have proactively recognized this link by directly referencing the SDgs in their OGP action plans, or in specific open government commitments.

Back to Implementing SDG16+ Through the Open Government Partnership