Indonesia Results Report 2020-2022

- Action Plan: Indonesia Action Plan 2020-2022

- Dates Under Review: 2020-2022

- Report Publication Year: 2023

Indonesia’s sixth action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... improved access to information on social welfare programs, public procurementTransparency in the procurement process can help combat corruption and waste that plagues a significant portion of public procurement budgets globally. Technical specifications: Commitments that aim t... More, and beneficial ownershipDisclosing beneficial owners — those who ultimately control or profit from a business — is essential for combating corruption, stemming illicit financial flows, and fighting tax evasion. Technical... More. Many commitments benefited from government-civil society collaboration. Both Open Government Indonesia and Open ParliamentEnsuring access to legislative information and creating mechanisms for public participation are critical to building an open, trusting relationship with citizens. Technical specifications: Commitments... More Indonesia published new repositories on commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... implementation.

Early ResultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More:

Early ResultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More:

This action plan made major progress on expanding access to information on social welfare eligibility for millions of Indonesians (Commitment 11). This reform was an exemplary open government achievement for Indonesia. Among the other three commitments that IRM identified as having the potential to realize the most promising results at the design phase, two achieved notable early results. Commitment 1 made marginal progress on opening access to public procurement information by instituting a revised Information Commission RegulationGovernment reformers are developing regulations that enshrine values of transparency, participation, and accountability in government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or reforming ... on Public Information Service Standards. Commitment 17 also made marginal progress on beneficial ownership transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More, providing free access to the Ministry of Law and Human Rights’ public register.

Among the action plan’s other commitments, half produced marginal early results in opening government, struggling with implementation obstacles or gaps in the design of intended reforms. For the open parliament commitments (19–24), most initiatives were internally focused. Although the commitments focused on access to justiceAccessible justice systems – both formal and informal – ensure that individuals and communities with legal needs know where to go for help, obtain the help they need, and move through a system tha... More (6–10) did not make major improvements to legal aid’s accessibility outside of major cities, they did result in positive steps, such as passing implementing regulations on accommodations for persons with disabilities in the Supreme Court and correctional institutions.

CompletionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More:

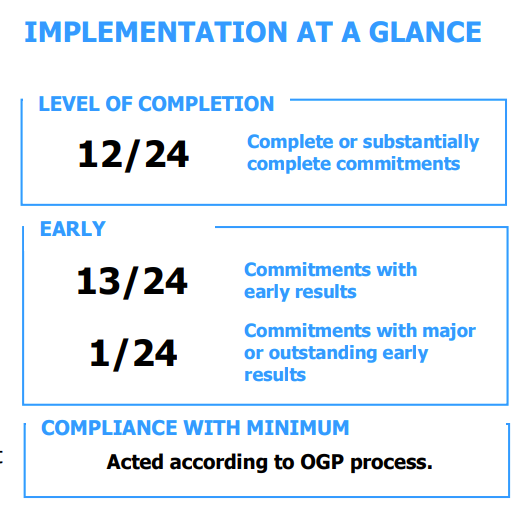

Half of the action plan’s commitments (12 of 24) were substantially or completely implemented, a slightly lower implementation rate than the previous plan (12 of 19). Among Indonesia’s open parliament commitments, one of six was substantially implemented. Obstacles to implementation included leadership turnover and lack of cross-parliamentary support for certain initiatives. As for the government action plan’s eighteen commitments, eleven were completely or substantially implemented—including the four most promising commitments (1, 11, 15, and 17). Enablers of implementation included strong civil-society-government collaboration and sufficient budget allocation by government or civil society stakeholders. Most of the open government commitments with limited implementation were civil society initiatives without sufficient uptake by necessary government stakeholders—for example, on access to justiceTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi... (7, 9, and 10) and protecting civic space (16 and 18).

Participation and Co-Creation:

Indonesia’s action plan was developed in two separate parts. Commitments 1–18 were directly proposed by civil society, often many organizations acting together, and were developed collaboratively. This process was led by Open Government Indonesia (OGI) Secretariat with a steering committeeThe Steering Committee is OGP’s executive decision-making body. Its role is to develop, promote and safeguard OGP’s values, principles and interests; establish OGP’s core ideas, policies, and ru... made up of eight government and one civil society representatives. The open parliament commitments (19–24) were developed through a separate process at the House of Representatives (DPR RI), which expanded civil society participation compared to the previous plan but did not include parliamentarians’ participation. This process was led by the Open Parliament Indonesia (OPI) Secretariat.

Collaboration in implementation varied across the action plan. Some commitments saw strong government and civil society co-implementation. In other cases, government implementers communicated updates on commitments, but did not offer opportunities for collaboration. Meanwhile, some government implementers preferred to consult with the OGI Secretariat, rather than maintain direct communication channels with civil society counterparts. Overall, during the implementation phase, Indonesia met the OGP Participation and Co-Creation StandardsCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders is at the heart of the OGP process. The Participation and Co-Creation Standards are intended to support this collaboration throug... by publishing OGI and OPI repositories, improving the transparency of open government efforts.

Implementation in Context:

The implementation period for this action plan followed Indonesia’s 2019 presidential election. As a result, a number of commitments were synchronized with the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2020–2024. However, OGI was not undergirded by a firm legal basis, such as a presidential decree. As a result, the government did not make priority budget allocations for the implementation of the commitments. In addition, government budget was often diverted to COVID-19 pandemic response and recovery efforts, and international donors have offered progressively limited aid for development and governance reforms in Indonesia.[1]

[1] Ben Davis, “Financial Sustainability and Funding Diversification: The Challenge for Indonesian NGOs,” https://www.ksi-indonesia.org/assets/uploads/original/2020/02/ksi-1580493181.pdf.

RPLA Reply

How does the Open Government Partnership promote transparency and accountability in government?