Italy Results Report 2021-2023

- Action Plan: Italy Action Plan 2021-2023 (December)

- Dates Under Review: 2021-2023

- Report Publication Year: 2024

Italy’s fifth action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... made progress opening public spending data on the National Recovery and Resilience Plan and institutionalizing civil society-public administration cooperation on the national anti-corruption framework. Co-creation and participation practices greatly improved compared to previous action plan cycles, with a new Multi Stakeholder Forum.

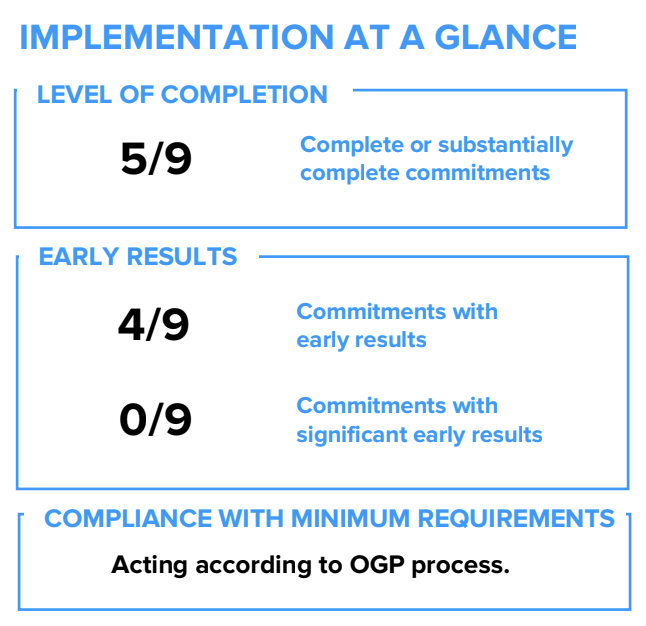

Four out of the 9 commitments in Italy’s fifth action plan produced moderate early results – an improvement compared to the previous action plan cycle[1]. No commitments achieved significant early results. Promising commitments identified by the IRM at the design phase generated the strongest results.[2] Commitments 2.01 and 2.02 resulted in cooperation between civil society and public administration on the national anti-corruption framework and delivered capacity buildingEnhancing the skills, abilities, and processes of public servants, civil society, and citizens is essential to achieving long-lasting results in opening government. Technical specifications: Set of ac... for key officials tasked with preventing corruption. This benefited from political visibility, given Italy’s Vice-Presidency of the G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group in 2023. CommitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 5.02 published new and higher-quality datasets on public spending tied to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), forming part of broader institutional actions. In addition, Commitment 1.01 formed an OGP multistakeholder forum.

Four out of the 9 commitments in Italy’s fifth action plan produced moderate early results – an improvement compared to the previous action plan cycle[1]. No commitments achieved significant early results. Promising commitments identified by the IRM at the design phase generated the strongest results.[2] Commitments 2.01 and 2.02 resulted in cooperation between civil society and public administration on the national anti-corruption framework and delivered capacity buildingEnhancing the skills, abilities, and processes of public servants, civil society, and citizens is essential to achieving long-lasting results in opening government. Technical specifications: Set of ac... for key officials tasked with preventing corruption. This benefited from political visibility, given Italy’s Vice-Presidency of the G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group in 2023. CommitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 5.02 published new and higher-quality datasets on public spending tied to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), forming part of broader institutional actions. In addition, Commitment 1.01 formed an OGP multistakeholder forum.

CompletionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More

This action plan had a higher implementation rate than the previous action plan.[3] Four commitments (2.01, 2.02, 3.02, and 5.02) achieved full completion and one (1.01) achieved substantial completion—including most commitments the IRM identified as having the potential to realize promising results at the design phase.[4] Contributing factors to implementation were inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More within broader institutionalized frameworks—such as that of the PNRR—and a positive approach to collaboration between public administration and civil society. The absence of these factors or changes to relevant legislative frameworks affected the degree of completion for the remaining commitments.

Participation and Co-Creation

A dedicated OGP Italy team within the Department of Public Function (DFP) led Italy’s OGP process. An OGP Task Force made up of experts on open government supported the process, along with the multistakeholder forum (MSF), which was established in July 2022. The MSF enabled a more structured and institutionally recognized pathway for cooperation between public administration and civil society. Through the MSF, improved governance of the OGP process had a noticeable trickle-down effect on the joint implementation of most commitments.[5] Co-creation and participation saw significant improvement compared to previous cycles. Public administration and civil society met frequently online and in person both during design and implementation of the action plan,[6] with a number of new CSO participants in the process. While praising the increased level of interaction, public administration and civil society stakeholders noted to the IRM that intensive workload formed a barrier for the participation of smaller civil society organizations who lack financial and human resources.[7] This can be addressed in future cycles, building on this action plan’s progress.

Implementation in Context

Steps taken to ensure close collaboration during co-creation of commitments had a positive effect on action plan implementation.[8] The new MSF ensured a more structured and sustainable approach to participation and co-creation throughout the entire action plan cycle, including for the implementation of most commitments. In some cases, commitment implementation benefited from external factors, like high-level exposure provided by Italy’s Vice-Presidency of the G20 Working Group on Anti-Corruption. A new government came into power in 2022, during the action plan period,[9] although this did not significantly affect the completion rate of commitments.[10] Italy demonstrated its commitment to OGP internationally while Co-Chair of the OGP Steering CommitteeThe Steering Committee is OGP’s executive decision-making body. Its role is to develop, promote and safeguard OGP’s values, principles and interests; establish OGP’s core ideas, policies, and ru... during the implementation period. Public administration and civil society stakeholders indicated that more high-level political support for the domestic process would have been beneficial to advance the open government agenda.

[1] “IRM Transitional Results Report: Italy 2019–2021,” Open Government Partnership, 28 March 2022, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Italy_Transitional-Results-Report_2019-2021_EN.pdf.

[2] “IRM Action Plan Review: Italy 2022–2023,” Open Government Partnership, 14 October 2022, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Italy_Action-Plan-Review_2021-2023_EN.pdf.

[3] “IRM Transitional Results Report: Italy 2019–2021,” Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More.

[4] “IRM Action Plan Review: Italy 2022–2023,” Open Government Partnership.

[5] “Italy End-of-Term Self-Assessment 2022–2023,” OGP Italy, 29 January 2024, https://open.gov.it/sites/default/ files/media/documents/2024-01/20242901-Rapporto autovalutazione finale 5NAP.pdf; Department of Public Function, interview by IRM researcher, 11 January 2024; National School of Administration, interview by IRM researcher, 16 January 2024; Libera, interview by IRM researcher, 19 January 2024; Bank of Italy, interview by IRM researcher, 22 January 2024.

[6] “Italy End-of-Term Self-Assessment 2022–2023,” Department of Public Function.

[7] Department of Public Function, interview; Libera, interview.

[8] “Italy End-of-Term Self-Assessment 2022–2023,” Department of Public Function; Department of Public Function, interview.

[9] “Meloni Government,” Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 22 October 2022, https://www.governo.it/it/i-governi-dal-1943-ad-oggi/governo-meloni/20727.

[10] Department of Public Function, interview.

Downloads

- Italy_Results Report_2021-2023_IT

- Italy_Results Report_2021-2023_EN

- Italy_Results Report_2021-2023_CommentsReceived

Leave a Reply