Justice Policy Series, Part II: Open Justice

About OGP and Justice

In this report: |

The Open Government Partnership (OGP) provides an opportunity for government and civil society reformers to make government more transparent, participatory, inclusive, and accountable. Working together, government and civil society co-create two-year action plans with concrete commitments across a broad range of issues. All commitments are then monitored by OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM). Recently, thanks to increased global activity around justiceTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi..., many governments and civil society leaders are expressing growing interest in better linking justice with open government.

This paper is the second of three in a series on justice released as a part of the Open Government Partnership Global Report. In 2019, OGP released the series’ first installment, Access to Justice, which focused on how open government can help people identify and address their legal needs. In the coming months, the OGP will issue the third installment on justice as a means to enforce open government.[1] The series aims to show how open government can make accountable, credible improvements to justice systems. The aim of this report is to inspire countries to adopt policies and activities suggested here and adapt them for their own national and local context. Working closely with international and domestic partners, the OGP Support UnitThe OGP Support Unit is a small, permanent group of staff that work closely with the Steering Committee and the Independent Reporting Mechanism to advance the goals of the Open Government Partnership.... will use this research to help OGP members continue to develop and implement strong justice commitments.

La publicación ahora está disponible en español aquí.

The Access to Justice paper can be found here. The Global Report can be found here.

Find the whole Justice Policy Series here.

Introduction

Key Takeaways

- Open justiceAn open, independent, and impartial justice system serves as a foundation for better access to justice by fulfilling all people’s civil liberties and allowing individuals to more effectively protect... is a first step to fairer justice systems. Open justice reforms, including those that make justice system actors more transparent and accountable to citizens, can serve as a first step to addressing issues of fairness and independence.

- A full set of justice reforms will need to move beyond courts. Opening the justice system requires proactive work on the part of many actors, including courts, police, prosecutors, legal aidMore and better information about aid helps partner countries and donor institutions plan and manage aid resources more effectively, parliaments and civil society to hold governments accountable for t... providers, and pretrial and corrections services.

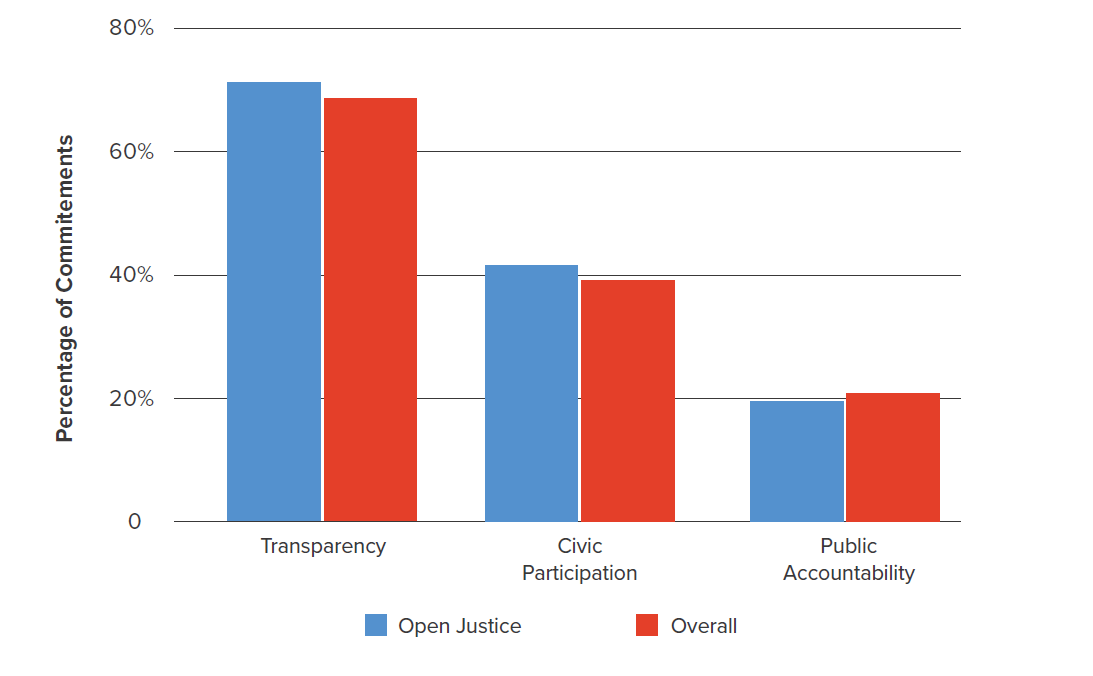

- Existing OGP commitments tend to focus on transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More. As in other areas, most OGP open justice commitments focus on making justice institutions more transparent. OGP members can build on these initiatives with commitments that also guarantee accountability mechanisms that strengthen the justice system’s independence, impartiality, and integrity.

The Open Government Partnership provides an opportunity for government and civil society reformers to make government more transparent, participatory, inclusive, and accountable. Working together, government and civil society co-create two-year action plans with concrete commitments across a broad range of issues. All commitments are then monitored by OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM).[2] Thanks to increased global activity around justice in the last few years, a growing number of OGP members have begun to use their action plans to focus on reforms in the justice sector. Among these reforms, the largest subset focuses on making justice actors and institutions more transparent and subject to public scrutiny and monitoring.

What is Justice and the Justice System?

Although the concept of justice itself has several definitions, this article focuses on legal justice – that is, the idea that all people should receive the benefits, protections, and rights granted by law. The justice system, then, is the network of actors and institutions tasked with ensuring that justice is upheld. At a minimum, the justice system includes courts, judicial officials, and police. However, in most countries, the justice system also includes administrative tribunals and organizations around them – whether dealing with taxPlacing transparency, accountability, and participation at the center of tax policy can ensure that burdens are distributed equitably across society. Technical specifications: Commitments related to c..., immigration, or other issues. In some countries and regions, traditional or religious leaders may be part of the justice system. This paper is largely focused on the formal elements of the justice system. Yet it is important to keep these broad definitions in mind, as some administrative bodies – such as immigration courts – might be exempted from transparency and oversight practices common in the judiciaryWhile a majority of open government reforms occur within the executive branch, OGP members are increasingly taking on commitments to increase the openness of the judicial branch. Technical specificati....

Though each of these actors is equally important in the communities they serve, it would be impossible to cover them all in one paper. Instead, this paper focuses on challenges and possible solutions for six actors that tend to be universal – and universally powerful – across legal systems. These actors are:

- Courts and judicial officials

- Police

- Prosecutors

- Legal aid

- Pretrial services

- Corrections

What is Open Justice?

Open justice applies the principles of open government – transparency, civic participation, and public accountabilityAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, public accountability occurs when ”rules, regulations, and mechanisms in place call upon government actors to justify their actions, act upon criticisms ... More – to the justice system. These principles are not only important for courts, but also for the many other actors that play a role in the delivery of justice services.

Other Dimensions of Justice

This paper is the second of three in a series on justice released as a part of the Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More Global Report. While each installment focuses on a distinct dimension of justice, all three elements are closely linked. The other papers in the series are as follows:

- Access to Justice: focuses on how open government can help people identify and take action to address their legal needs.

- Justice for Enforcing Open Government: covers the ways in which the justice system can enforce the open government values of transparency, civic participation, and public accountability.

Why Open Justice?

The principles of open government – transparency, civic participation, and public accountability – are essential to a fair and effective justice system for several reasons that can be divided into two main categories:

Normative and Legal

- The principles of open justice are woven through international law and standards. The right to due process is enshrined in Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[3] and Articles 9-11 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).[4]

- An open justice system helps ensure that other civil and political rights are respected. When justice actors and processes are opaque and closed off from public scrutiny, the public are less able to verify that they effectively uphold citizens’ rights or identify violations of those rights. An open, independent, and impartial justice system serves as a foundation for better access to justiceAccessible justice systems – both formal and informal – ensure that individuals and communities with legal needs know where to go for help, obtain the help they need, and move through a system tha... More by fulfilling all people’s civil liberties and allowing individuals to more effectively protect their rights.

Instrumental

- Open justice underpins the rule of law. Justice actors and processes that are transparent and subject to independent oversight enable rule by law and help ensure an orderly and fair society.[5]

- Open justice supports equitable growth and development. In strengthening the rule of law, open justice can help countries achieve economic and social progress by curbing corruption, limiting abuse of power, and guaranteeing access to key public services.[6]

- An open justice system allows for peaceful and reliable conflict resolution mechanisms. Open justice reforms improve the quality of justice and make justice institutions fairer, in turn, increasing their legitimacy in the eyes of the public. People can depend on these institutions to resolve conflict peacefully rather than by resorting to violence.

What Do Open Justice Reforms Look Like?

Each of the three principles of open government presents specific implications for the operations of justice system actors. OGP staff discussed the issue with dozens of OGP partners (through interviews and consultations), scoured OGP results, and undertook a significant process of review and revision. Drawing on the information uncovered through these steps, this paper identifies some of the most important reforms, examples of which follow. Each section of the paper will offer examples of these reforms from countries inside and outside of OGP. Briefly, definitions and examples of open justice reforms following each of the open government principles are as follows:

Transparency: Government disclosure of information or improvement of the quality of information disclosed to the public. Provisions and activities to ensure transparency in the justice system could include the following:

- Open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici...

- Clear, publicly available operating procedures

- Public access to decisions and opinions

- Information about public officials

Civic Participation: The ability of the public to inform or influence government processes and decision-making. Provisions and activities to ensure civic participation in the justice system could include the following:

- Processes for public complaints about justice system actors

- Citizen and/or publicly observable independent oversight boards

- Participatory budgeting processes

- Legal aid providers and other members of civil society that make information about the justice system and justice processes more accessible

Public Accountability: Opportunities to hold officials answerable or subject them to sanctions for their actions. Provisions and activities to ensure public accountability in the justice system could include the following:

- Processes for public complaints about justice system actors

- Citizen and/or publicly observable independent oversight boards

- Fair disciplinary processes that allow for sanctions and removal, the details of which are publicly available

Note: In the case of justice actors, and especially judicial officials, increased accountability must be carefully balanced with considerations of impartiality and independence. Public accountability reforms must not jeopardize judicial independence.

PARTNERS WORKING ON OPEN JUSTICE The following are some of the organizations and international bodies working on open justice topics:

|

Open Justice in OGP

- Justice is one of the most common areas of focus in OGP action plans. Justice has grown as an area of focus in OGP action plans over the last several cycles thanks to growing global momentum for action and innovation in the justice sector.[7] As of July 2020, OGP members have collectively made nearly 300 commitments that focus on making justice more accessible, open, and effective.

- Among justice commitments, the largest subset (137 commitments) are related to topics in open justice. To date, most of these commitments have focused on transforming the courts (see Figure I) and fewer have aimed to make improvements to other important justice system actors.

- Open justice commitments are disproportionately concentrated in the Americas. Fifty percent of all open justice commitments are from members in the Americas region while the Americas only represent a third of commitments overall.

- Open justice commitments tend to be more effective than other commitments. In terms of results, according to data from IRM reports, 25% of open justice commitments have led to significant improvements in government practice. This is higher than other justice commitments overall (21%) and OGP commitments overall (19%).

- The majority of open justice commitments focus on the transparency of justice institutions by making information and data more accessible. This pattern mirrors trends in OGP commitments overall (see Figure 2). These reforms are too rarely coupled with measures that allow civil society and the public to monitor these actors and hold them accountable when they take actions that could harm the citizens they serve.

Figure 1. Open Justice Commitments by Actor

| Actor* | Number of Commitments |

|---|---|

| Courts | 72 |

| Police | 18 |

| Prosecutors | 13 |

| Pretrial Services & Corrections | 9 |

| Legal Aid | 7 |

*Categories are not mutually exclusive since one commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... might affect multiple actors.

Figure 2. Commitment RelevanceAccording to the OGP Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should include a clear open government lens. Specifically, they should advance at least one of the OGP values: transparency, citizen partic... to OGP Values

Objectives and Contents

This paper suggests a way forward in an area that faces several complex and growing challenges. In 2020, the rule of law has declined in more countries than it has improved in, continuing a three-year trend.[8] In many countries, corruption is on the rise while respect for fundamental rights and constraints on government power continue to deteriorate.[9]

Open justice reforms can serve as an antidote to these concerning developments. As the data in the previous section indicates, OGP commitments often make significant improvements to governance outcomes. However, to continue this momentum, more governments across all regions must make justice – and in particular, open justice – a priority in their action plans. Recognizing that each justice system is different and various actors within these systems face unique challenges, the international community must propose adaptable solutions that address countries’ needs.

This paper responds to these concerns by offering emerging guidance, examples, and recommendations for the types of open government reforms justice systems may undertake to advance open justice in their institutions. The paper will be useful to practitioners and reformers in government or civil society looking for ideas to tackle some of the issues their justice system faces and case studies, as well as success stories from other countries. In the longer term, the paper seeks to encourage more OGP members to commit to open justice reforms in their action plans, so in this way, the paper is especially relevant to members of the OGP community. However, the suggestions and examples are also applicable to a broader audience of reformers interested in justice.

Importantly, this paper is not exhaustive, and many examples and approaches may be missing from the pages that follow. Similarly, the guidance provided here is not comprehensive and therefore should not be viewed as an instruction manual or best practices guide for open justice reforms. Instead, this paper will be most useful to reformers as a foundation for brainstorming ideas, an entry point for peer learning, and a starting point for seeking further resources.

This paper comprises nine chapters, covering the justice system actors and topics listed in the previous section. Each chapter begins with the following:

- An overview of the topic and its relevance to open government

- A discussion of the reasons open justice reforms stand to improve the function of the justice institution in question.

The body of each chapter includes the following sections:

- Examples of OGP commitments on the topic

- Case studies from around the world of unique and/or successful reforms

- Relevant international and regional guidance

- Recommendations and example reforms

Courts

OPEN COURT DATA

Overview

As the branch of government that is least responsive to changing public opinion, judiciaries have also been slow to embrace the institutional transparency that has increasingly become the expectation in many countries. Efforts to maintain judicial independence and protect courts from undue political influence often result in a dearth of publicly available court information.

Yet as open access to government data becomes the norm across societies, the courts are increasingly inundated with data requests and are falling behind on their disclosure obligations. These requests may be better served by proactively releasing court data, for example, data related to case status, charges, pleadings, motions, judgments, and sentencing. Additionally, as more courts use algorithms to automate processes such as pre-trial risk assessments and sentencing decisions, proactive algorithmic transparency can help identify and prevent instances of bias and discrimination. Proactively publishing these data can improve the responsiveness of the justice system, incentivizing fair and efficient court activity. It also promotes public trust in judicial institutions, which is crucial for the rule of law.

Recommendations and Sample Reforms

The following are actions judiciaries and governments can take to improve the transparency of their court systems, listed from simplest to implement to more advanced.

- Publish basic judicial data. Begin by publishing information about what takes place in the courtroom.[10] For example, a survey of open judicial data regimes finds that judicial data sets should at least include court decisions, case registers, filed document records, and statistical data.[11]

- Ensure operational transparency. Collect information that allows measurement of how judicial officials do their jobs. This includes information about how many cases judicial officials are assigned in a year, how quickly they process the cases on their docket, how many cases they complete in a year, how they decide cases, and how frequently their rulings are overturned on appeal.[12]

- Ensure algorithmic transparency. The use of automated decision-making technology and the algorithms employed should be disclosed to identify and prevent discrimination.[13]

- Post-case filings and decisions in proceedings. Make documentation available at the individual case level by publishing, for example, charges, transcripts from hearings and depositions, judgments, and the reasoning for judgments. Courts should take into account methods of protecting the privacy of vulnerable individuals, such as victims of crime or children, when releasing this information.[14] Courts can also publish information about processes to ensure privacy protection, for example, in family law cases.

- Identify and remedy inequity. Collect, maintain, and report court data regarding race, ethnicity, geography, class, and religion that allow courts to identify and remedy racial and other disparities. See the resolution from the Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrators (US).[15]

- Improve accessibility of court data. Create a centralized portal for court data and allow bulk data downloads to enable access to all court data from a single source.

- Standardize court data. Ensure that courts in different jurisdictions and at different levels of the judicial system standardize the content and format of the data sets they disclose. This may include improving the linkages between data at different instances.

Buenos Aires criminal courts publish a repositoryAccess to relevant information is essential for enabling participation and ensuring accountability throughout the OGP process. An OGP repository is an online centralized website, webpage, platform or ... of decisions

Criminal Courts 10 and 13 both created an open data repository with all judgments organized by the type of felony, the type of punishment, a description of the case, and a link to the complete decision. The court makes special efforts to anonymize the data to address privacy concerns. Court 13 also publishes plain-language versions of its decisions. Both courts open hearings to the public and publish a schedule of hearings in advance.

Colombia improves judicial services through court transparency

After a 2015 declaration by the Council of State (Colombia’s highest administrative court) to improve transparency and accountability in the justice system, Colombia established the Transparency and Accountability Commission, which was tasked with taking up this initiative. As part of its work, the commission led a 2015 OGP commitment through which they began to publish court data and information, including court memoranda and decisions, information about the court’s officials, and the court’s agenda.[16] As part of the commitment, the Council of State also published procedural manuals for a variety of court processes, such as the tutela, a constitutional rights protection claim available to all citizens. These measures helped the Council of State become more transparent than ever before. Still, corruption and distrust of justice institutions continued, and Colombia extended its efforts into its subsequent action plan. The Council of State’s 2017 commitment aims to implement a variety of digital tools to further increase the court’s transparency, including technological tools that allow citizens to monitor the magistrate election process, a mechanism for citizens to submit complaints and claims online, and better documentation of court processes and requirements.[17]

- Czech Republic: Publish all district, regional, and high court decisions in a searchable online database (2018-2020).

- Greece: Create a publicly accessible case-law database including anonymized decisions of all administrative courts (2019-2021).

- Paraguay: Create an open justice data portal (2018-2020).

- Slovakia: Create a system to ensure uniform reporting of all judicial decisions (2015-2017).

- Uruguay: Publish video recordings of all public hearings, as well as statistical information from the judicial branch (2016-2018, 2018-2020).

Guidance and Standards

The National Center for State Courts – National Open Courts Data Standard (NODS)

In 2018, two US civil society organizations – the National Center for State Courts and Measures for Justice – partnered to create the NODS .[18] The project seeks to provide publicly available standardized, case-level court data to improve court system transparency and improve public policy. NODS includes case-level reporting in a variety of areas, such as the following:

- Case status and details

- Litigant and lawyer information

- Pleadings

- Motions, filings, and orders

- Charges

- Judgments

- Sanctions

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Resources (UNODC)

UNODC and its Global Judicial Integrity Network provide guidance on how judiciaries can improve and strengthen their systems for the management of courts and cases, maintenance of records, and transparency in the judicial system, in particular through the Implementation Guide and Evaluative Framework for Article 11 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption[19] and the Resource Guide on Strengthening Judicial Integrity and Capacity.[20] The network also promotes peer learning and information sharing on these topics through various activities, including podcasts, opinion editorials, and webinars.

JUDICIAL OFFICERS – APPOINTMENT AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Overview

Judicial officers – including judges, magistrates, and other officials with powers to facilitate and decide legal disputes – have the authority to protect human rightsAn essential part of open government includes protecting the sacred freedoms and rights of all citizens, including the most vulnerable groups, and holding those who violate human rights accountable. T..., make wrongs right, and resolve intractable conflicts. As such, their appointment (or election where applicable) must be transparent, based on objective criteria, and free of corruption so that the public has faith in their independence, impartiality, and integrity. Transparent appointments also help the public hold appointing authorities accountable in selecting qualified judicial officers.

Once judicial officers have assumed their role, their conduct and track record matter. Justice systems can make judicial officers’ decisions or rulings publicly available (except in cases when privacy must be considered) to ensure the fairness and predictability of the system.[21] More generally, judicial officers must abide by relevant standards of professional conduct and act with independence, impartiality, and integrity. If they fail to meet these standards, judicial officers should be accountable through a complaints procedure that allows for a review of their conduct by an independent oversight authority capable of fair proceedings and discipline, including removal. The outcomes of complaints and any disciplinary proceedings should be made publicly available and transparent.

Importantly, countries considering reforms in this area should take into account that accountability mechanisms for judicial officers should not in any way threaten judicial independence and should therefore differ from accountability mechanisms for other branches of government. In particular, promotions, terminations, and disciplinary actions should never be determined on political grounds and must be shielded from undue influence by the executive branch (see Principles 11-20 of the Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary referenced later in this chapter).

Recommendations and Sample Reforms

OGP members can take the following actions to improve meritorious, transparent judicial appointments:

- Publish necessary qualifications and examination standards. If recruitment occurs via examinations, they should be established by the state with common, transparent standards and given anonymously.[22] Ensure that standards are nondiscriminatory and genderOGP participating governments are bringing gender perspectives to popular policy areas, ensuring diversity in participatory processes, and specifically targeting gender gaps in policies to address gov... More and ethno-culturally neutral.

- Publish term limits and appointment terms. Transparent term limits, mandatory retirement ages, or lifetime appointments insulate the judiciary from political purging.

- Require transparent nominations. If recruitment occurs via nomination and appointment, the procedure should be fully transparent to reveal the candidate’s qualifications vis-à-vis other publicly announced candidates to avoid political favoritism.[23]

- Publicly vet candidates. Consider publicizing interviews of candidates. Allow feedback on candidates from the legal profession and civil society to hear external evidence of a candidate’s fitness. Publicize reasons for final appointments.

- Require judicial officials to declare assets and financial interests. This includes outside activities, employment, investments, assets, and substantial gifts and benefits from which a conflict may result.[24]

- Publicize and report on measures to diversify judicial officers, through recruitment, retention, and training. Take measures so that judicial officials reflect the gender balance and social diversity of the country.[25]

The following are actions judiciaries and governments can take to improve judicial accountability and independence:

- Publish a judicial code of conduct. Write and publish codes that support a learned, independent, and impartial judiciary. Making these codes publicly accessible allows citizens to hold the judiciary accountable by filing suit for egregious errors. See the Global Judicial Integrity Network’s “Guide on Resource Guide on Strengthening Judicial Integrity“[26] for more guidance.

- Involve justices in developing standards. Invite judicial involvement in creating and updating codes of conduct. Ownership of ethical standards promotes compliance.

- Perform comprehensive evaluations. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) provides a list of data that should be collected[27] to assess a court system, including which sources can provide pertinent information and what questions should be asked when analyzing this information. Note: Evaluations should not include successful appeals against judicial officials’ rulings, as this might affect their decision-making.

- Implement and publish court self-evaluations. Self-assessment mechanisms, such as the one offered by the UNODC Implementation Guide and Evaluative Framework for Article 11 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption[28] and the International Consortium for Court Excellence,[29] can help courts maintain accessible, efficient, and innovative services.

- Use and publish disciplinary measures. Facilitate accountability by accepting feedback from both judicial members and the public. Ensure that disciplinary standards address all judicial integrity issues, including cases of gender bias, sex discrimination, and sexual misconduct. Disciplinary measures should be proportionate to the offense and might range from internal written warnings to public acknowledgment of ethical deviations to removal from office.[30]

- Adopt continuing education programs. Programs can discuss legislative developments, judicial ethics, docket management, technology use, and international developments. This education should be accessible to all judicial officials and include various learning methods (e.g., self-learning, in-person, or interactive learning).[31]

- Facilitate judicial integrity networking. For example, the Global Judicial Integrity Network offers networking opportunities at the local, regional, and global level. Limit initial meetings focusing on judicial integrity to only judicial officials to allow for free and open peer-to-peer discussion before inviting public participationGiving citizens opportunities to provide input into government decision-making leads to more effective governance, improved public service delivery, and more equitable outcomes. Technical specificatio....

- Publish judicial decisions. Access to the country’s laws and judicial decisions should be free. Some decisions may need to be withheld or anonymized to protect privacy concerns, including the identity of juveniles.[32]

Kenya initiates judicial vetting

In 2010, Kenya approved a new democratic constitution by public referendum. In response to years of government corruption, including at high levels of the judiciary, the framers sought to enshrine democratic institutions and the rule of law in the new constitution. To do so, they included a provision that stipulates all judicial officials and magistrates appointed under the previous constitution undergo vetting by an independent board. The details of this provision are affirmed in a 2011 law that the judicial official and magistrate vetting board would comprise nine members, including six citizens, three of whom must be lawyers. Following this legislation, Kenya made an OGP commitment in 2012 to implement the newly required processes. Throughout 2012, the board vetted dozens of judicial officials at various levels of the judiciary and determined that several officials were unfit to serve. Putting the judiciary under the microscope in this way helped restore citizen trust in and legitimacy to the institution in a new era. However, while innovative, this approach was not without controversy, and civil society raised concerns that lawyers on the board were too lenient on some judicial officials alleged to have engaged in corruption while removing other judicial officials without legitimate reasoning.

Denmark establishes whistleblower portals for justice system employees

Following revelations in 2018 that senior justice officials had withheld key documents in an investigation of police misconduct during a 2012 protest against Chinese President Hu Jintao’s state visit, Denmark made an OGP commitment in 2019 to improve accountability for justice system officials.[33],[34] The commitment seeks to establish a whistleblower scheme in the Ministry of Justice, prosecutor service, police, and prison service, among other justice system institutions. The new procedures will provide mechanisms through which employees or partners of any of these institutions can report individual or systemic wrongdoing. The online portal will also allow whistleblowers to file their complaints anonymously and enable the authorities investigating the complaints to communicate with whistleblowers while maintaining their anonymity. This system could allow for great accountability for justice system officials and, ultimately, the provision of fairer justice services.

Slovak Republic legislates transparent selection of judicial officials

The Slovak Republic used its 2017 action plan to help address weak judicial independence and a lack of public trust in judicial decisions.[35] Among other reforms, the country passed legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r... that standardized selection procedures for judicial officials and established a committee that will oversee such processes in the future. Information about these procedures – including lists of candidates and their résumés – is now publicly available online, which allows for public scrutiny of the candidates as well. Over time, reforms like this one can help build public trust in judicial institutions.

- Argentina: Publish information about selection processes, complaint mechanisms, and disciplinary procedures for judicial officials (2017-2019).

- Costa Rica: Develop an online “judicial observatory system,” which enables citizens to monitor how long open cases take to be concluded (2019-2021).

- Jalisco, Mexico: Implement safeguards to avoid judicial officials’ conflicts of interest by working with citizens to review and update the system for selecting expert witnesses during trials (2019-2021).

- Paraguay: Publish accusations and disciplinary procedures against judicial officials more transparently for citizens through an online digital system (2018-2020).

Guidance and Standards

The United Nations – Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary

The UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary,[36] adopted by the UN Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders and endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 1985, lays out 20 principles to secure and promote the independence of the judiciary.

- Principle 10, related to qualifications, selection, and training, provides the following:

- 10. Persons selected for judicial office shall be individuals of integrity and ability with appropriate training or qualifications in law. Any method of judicial selection shall safeguard against judicial appointments for improper motives. In the selection of judicial officials, there shall be no discrimination against a person on the grounds of race, colour, sex, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or status, except that a requirement, that a candidate for judicial office must be a national of the country concerned, shall not be considered discriminatory.

- Principles 17-20, related to discipline, suspension, and removal, provide the following:

- 17. A charge or complaint made against a judicial official in his/her judicial and professional capacity shall be processed expeditiously and fairly under an appropriate procedure. The judicial official shall have the right to a fair hearing. The examination of the matter at its initial stage shall be kept confidential, unless otherwise requested by the judicial official.

- 18. judicial officials shall be subject to suspension or removal only for reasons of incapacity or behaviour that renders them unfit to discharge their duties.

- 19. All disciplinary, suspension, or removal proceedings shall be determined in accordance with established standards of judicial conduct.

- 20. Decisions in disciplinary, suspension, or removal proceedings should be subject to an independent review. This principle may not apply to the decisions of the highest court and those of the legislature in impeachment or similar proceedings.

The United Nations – Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct

The Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct,[37] developed in 2002 by the Judicial Integrity Group and endorsed by the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations in 2006, establish standards for the ethical conduct of judicial officials and revolve around six values necessary for an effective and principled judiciary: independence, impartiality, integrity, equality, propriety, and competence and diligence. The Bangalore Principles are accompanied by a detailed Commentary published in 2007, which, among others, touches upon the issues of qualifications, selection, and training (paragraph 10) or conditions of service and tenure (paragraph 11).

The Global Judicial Integrity Network

Officially established in 2018, the Global Judicial Integrity Network[38] was launched by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. The network aims to promote peer learning and support activities, facilitate access to relevant tools and resources related to judicial integrity, and support the further development and effective implementation of principles of judicial conduct and the prevention of corruption within the justice system. Among its outputs, the Global Judicial Integrity Network has developed several knowledge products and tools addressing pertinent integrity-related topics, such as the development and implementation of codes of judicial conduct,[39] gender-related issues,[40] judicial officials’ use of social media,[41] and judicial ethics training.[42]

COURT MODERNIZATION

Overview

To ensure accessibility and fairness and to protect against corruption, courts must be able to manage cases efficiently and reliably. Although not a requirement for an efficient court system, digital technology has become an increasingly popular tool to modernize courts and achieve these outcomes. In particular, tools such as online case management systems and the availability of virtual court proceedings can help improve access to information about court processes and simplify court services. These tools can encompass a variety of services, including e-filing, case tracking, automatic notices to appear in court and hearing date reminders, online dispute resolution services, and the publication of digital recordings of court proceedings.

These features, when integrated into an online platform, improve access to information about justice processes, allow citizens to engage with the system remotely – especially those who have traditionally lacked access to such processes – and reduce wait times by freeing up judicial officials’ and other court employees’ time. Furthermore, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, online court processes can help courts avoid inefficiencies and increase the accessibility of their services while mitigating public health risks.

Recommendations and Sample Reforms

The following are actions for governments implementing or considering implementing online case management systems to ensure that they maximize the transparency and accountability of the court system.

- Ensure that automation is an appropriate response to court system needs. Often court backlogs can result from a variety of issues, including corruption among court officials or a lack of communication and trust between justice sector institutions. While court automation can improve efficiency, it will not solve these underlying issues.

- Engage potential users early on to encourage trust and transparency in the new system. Court automation often presents major changes to how courts operate. Transparency about these changes and the potential improvements that may result could help combat skepticism, among court staff, litigants, lawyers, bar associations, and the general public. User-test technology with the public during development. Verify that the system meets user needs by ensuring accessibility, use of plain language, and availability in all languages commonly spoken among the population that the system serves.[43]

- Standardize the collection and presentation of information. Ensure that courts across different jurisdictions and across various levels of the system collect the same information to allow for cross-comparison.

- Provide access to information to litigants and the public. Automated systems have great potential to lower barriers to access to public information. Records requests, information on pending litigation, and notices of disposition can be substantially streamlined by automation.

- Extend court modernization to other parts of the court system. Court modernization is often piloted in one or a few courts. If pilots are successful, justice systems can begin implementation across the system to specialized courts, other jurisdictions, and other levels of the court system.

- Focus on interagency communication and interoperability within government. Courts can conserve significant resources by designing systems that facilitate efficient communication with other courts, correctional facilities, and agencies that manage identity, financial, and land records.

- Consider how e-court processes can improve efficiency during the Covid-19 pandemic. Processes such as e-filing, online dispute resolution, digital case look-up, and/or remote hearings can enable courts to continue proceedings in light of the ongoing public health risks of conducting such processes in person.[44]

- Conduct training for judicial officials and court staff. Court automation systems will work best if court staff use and maintain them properly. Comprehensive training, often including training on basic computer skills, can improve uptake.

- Implement effective monitoring and evaluation processes. Monitoring is an important accountability mechanism to ensure that the investment in court automation is used effectively to serve citizens by improving access to justice. These could include backlog reduction indicators and court user surveys that could help courts evaluate citizens’ engagement with the new system.

Kenya’s commercial courts are transitioning to e-court processes.

Without a system for electronic filing, court records in Kenya have been maintained in libraries of thousands of often-disorganized paper documents. This makes it challenging for court officials to keep track of cases, leading to debilitating backlogs for judicial officials and delayed judgments for citizens. In 2012, Kenya made an OGP commitment to modernize the judiciary with the goal of improving the courts’ efficiency, transparency, and accountability.[45] Among the initiatives included in the commitment, Kenya implemented software that would allow case proceedings and judgments to be made available online, enabling Kenyans to access and download cases and judgments online for the first time. The government also hoped to implement software that would randomly assign new cases to judicial officials to avoid bias and conflicts of interest in judgments, although this was not achieved by the end of the action plan. This has allowed scholars to identify significant ethnic bias in judicial decisions, pointing to the need to improve recruitment and training in high courts.[46]

Building on these initiatives, in 2017, Kenya continued attempts to digitize and automate certain court processes to address case backlogs and delays.[47] In a pilot carried out at the Commercial and Tax division of the High Court, the Kenyan judiciary began digitizing case files and centralizing them using case management software.[48] The system also includes a variety of other functions aimed at making court information more accessible and proceedings more efficient. For example, a public-facing case-tracking portal allows court users to check the status of their case online, and an e-payment platform helps citizens navigate the previously complex fee payment processes.

- Albania: Implement an online inspection, make judicial hearings available online through their integrated case management system, and digitize court files to simplify transferring information between court levels of the judiciary (2012-2014).

- Brazil: Implement an electronic system for judicial proceedings in the electoral courts to reduce court delays (2016–2018).

- Costa Rica: Create an online observatory to ensure efficient management of cases and reduce delays in delivering decisions (2019–2020).

- Greece: Implement an electronic system to monitor the status of all pending cases and allow electronic submission of documents for all parties (2016–2018).

- Montenegro: Establish the National Administrative Fee Collection System in order to simplify the payment of court fees for citizens and improve monitoring of outstanding payments (2018–2020).

Guidance and Standards

United States: The National Center for State Courts – Consolidated Case Management Functional Standards

The installation of case management software will not on its own ensure greater efficiency and openness. It must also be sustainable and user-friendly and collect the right information. The National Center for State Courts in the U.S. published its Consolidated Case Management Functional Standards in 2006.[49] These standards describe general capabilities that courts’ systems should support in a variety of categories, including the following:

- Scheduling

- Docket management

- Document creation and tracking

- Records management

- Court proceedings recording

Courts – Resources and Partners

Resources

- The International Consortium for Court Excellence publishes the Court Excellence Self-Assessment Questionnaire, which enables courts to evaluate their performance in seven areas.

- The National Center for State Courts produces resources for using technology in courts and case flow management.

- USAID’s Designing and Implementing Court Automation Projects outlines key considerations for court modernization.

- UNDP’s Judicial Integrity Self-Assessment Checklist is a useful tool to help judiciaries assess their courts.

- The Global Judicial Integrity Network’s resources include a guide on How to Develop and Implement Codes of Judicial Conduct.

- UNODC’s Resource Guide on Strengthening Judicial Capacity and Integrity outlines best practices for a variety of court processes, including court transparency, judicial official recruitment, evaluation, selection, and disciplinary measures.

Organizations

- Center for Court Innovation

- Global Judicial Integrity Network (established by UNODC)

- International Consortium for Court Excellence

- National Center for State Courts (NCSC) (United States) and NCSC International

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

Police

OPEN POLICE DATA

Overview

A lack of transparent or comparable police data inhibits the public and policymakers’ ability to fully understand and address problematic police practices and their consequences. OGP members are increasingly taking the initiative to open police data with the ultimate aim of evidence-based police reform.

Transparent data on police-citizen interaction is a vital tool to assess the efficacy and fairness of interactions between citizens and the police. Open data in areas like public complaints, officer-involved deaths, and use of force provides the foundation for informed research, policy reforms, and oversight. Specifically, open data enables evaluation of law enforcement’s fairness in their interactions with the public. Separately, the publication of police department budgets and expenditures ensures that public funding of law enforcement meets the needs of all citizens. Therefore, requiring police departments to provide accessible data is an essential first step toward strengthening public accountability and building public trust. Of course, police departments must also be cautious to protect individuals’ right to privacy and need to have fair, well-publicized processes for ensuring that open data respects the rights of victims, witnesses, and the accused.

Recommendations and Sample Reforms

The following are actions governments can take to ensure that they maximize the transparency and accountability of the police.

- Codify police data collection and publication in law. Amend policing and right to informationThe legal right to request information from the government allows the public to follow government decision-making, participate in ensuring better decisions, and hold the government accountable. Techni... legislation to require greater transparency.

- Involve citizens early. Convene law enforcement and public officials, civil society organizations, and members of the public to identify priority information for collection, disclosure, and privacy protection.

- Systematically collect and retain standardized policing data. Establish routine procedures that ensure various agencies use common terminology, categorization, and collection practices for data.

- Publish policing budget data. Regularly provide up-to-date data on government budgets for law enforcement as well as data on police expenditures. Aim to disclose information disaggregated at the police precinct level.

- Release data through an accessible online database. Provide current data in a free and downloadable format to ensure transparency. Provide disaggregated demographic data to measure the fairness of police interactions with the public and to facilitate analysis of particular patterns.

- Publish data-restriction policies. Publish, in clear and accessible language, information on standards and practices that inform what police information is classified or restricted. Include the public in shaping policies that determine what information is classified or restricted.

- Organize the data. Ensure that data can be downloaded, searched, and machine-read to facilitate researchers and community members’ data analysis.

- Develop standards for comparison. Comparable data enables better research and policy responses. While some governments may begin with a data standard, others will have more success in working toward cross-jurisdictional consensus on common data collected and published.

- Translate data into digestible formats. Provide graphics and written narratives that help the general public observe important trends and findings within the data.

- Facilitate data-driven publications and policy changes. Actively collaborate with civil society organizations, researchers, and other stakeholders to produce reports and recommendations based on findings from collaborative data analysis.

Open Police Data Initiative in the United States

The United States government undertook the Open Police Data Initiative[50] as part of its 2015 National Action Plan to address high levels of distrust and tension between police and the public.[51] The initiative encourages local police jurisdictions to proactively extract and publish policing data. The project is managed collaboratively by the Department of Justice’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services and the nonprofit organization, the National Police Foundation. The initiative increased access to information by creating a centralized database that comprises over 130 jurisdictions and 405 data sets as of June 2020, including cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and Detroit. The website also provides tools to extract, analyze, and publish data. This repository has led to published data sets in numerous areas, including on police use of force and officer-involved shootings. However, agency participation is voluntary, and the adoption rate remains low. Additionally, there is a need to improve data standardization and ensure regular updates. Recent unrest across the United States has reignited interest in open police data as reformers call for greater police transparency. This initiative demonstrates a viable process to further open police data with the ultimate aim to reduce bias and unnecessary use of force in policing tactics and increase public trust.

Legislating policing transparency in India

In 2009, India’s Parliament amended the Criminal Procedure Code to include a requirement that all police departments disclose information about arrests made. The law mandates that the information be published daily at the district level and include the names of arrested individuals and the names and designations of the police officers who arrested them. While this information raises concerns about privacy protections, it can be an important step for minimizing pretrial detention that does not comply with due process rights, especially in contexts where institutional protections against abuse of power and for access to justice may be weaker. Additionally, police headquarters must regularly collate this information at the state level, as well as information about the offenses for which arrested individuals were charged. All of this information is publicly available in the form of databases on the official websites of each state’s police department. For example, see Kerala State Police’s portal.[52] Separately, India’s National Crime Records Bureau has published the annual Crime in India Report since 1953, which contains crime data from across the country, including cases registered and persons arrested.[53]

- Austin, United States: Translate annual crime data file into accessible formats for the general public, such as written narratives and interactive maps (2019-2021).

- Liberia: Provide live police data on Liberia’s Open Data Portal that would include the location of police depots, actions against unprofessional police conduct, and crime maps (2015-2017).

- Mexico: Create a standardized prisoner registration system to more effectively keep track of arrests, sentences, and time spent in detention (2013-2015).

- United Kingdom: Bring police records under legislative control through the Public Records Act of 1958 to ensure long-term preservation and access (2013-2015).

Guidance and Standards

The UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) – Handbook on Police Accountability, Oversight, and Integrity

The handbook offers OGP countries several tangible actions to build a culture of transparency and accountability, as well as reliable statistics on police performance, integrity, and public confidence.[55] It encourages police reforms to be developed through public-police participation and not be simply prescriptive. Furthermore, the handbook gives guidance for external police oversight mechanisms:

- The mechanism should be required to issue regular reports to the government and the public on its activities.

- It should maintain a website with easily accessible information.

- It should respond in a timely fashion to citizen complaints.

- It should maintain detailed data on police abuses. Civilian oversight mechanisms are uniquely placed to conduct statistical or general reviews of patterns in police killings, including their causes, and should do so.

- Its budget and expenses should be publicly reported.[56]

The United States – Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st-Century Policing

Released in 2015, this report recommends that agencies should collect and make aggregate data publicly available.[57] Specific action items for police forces include the following:

- Collect, maintain, and report data to the federal government on all officer-involved shootings;

- Develop policies on what types of information will be released, when, and in what situation, to maintain transparency;

- Make public the demographic data regarding the composition of their force;

- Collect, maintain, and analyze demographic data on all detentions (stops, frisks, searches, summons, and arrests); and

- Disaggregate data by school and nonschool contacts.

Organizations for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) – Guidebook on Democratic Policing

The 2007 guidebook serves as a reference for police practitioners and policy-makers working to strengthen democratic policing and covers topics such as “policing ethics, and human rights standards; the essential nature of police accountability to the law and to the society they serve; as well as the need for their co-operation with the communities.”[58] In particular, the guidebook discusses key aspects of data oversight and disposal (sections 49-51) and police oversight (sections 84-94), including through data generated by citizen complaints.

OVERSIGHT AND MONITORING OF POLICE

Overview

Recent civil unrest in the United States and around the world has exposed high levels of public distrust toward police. This distrust is particularly strong among marginalized communities, who often face discrimination and disproportionate use of force at the hands of police around the world.[59]

There are a variety of means by which civil society groups and communities can hold police accountable for their actions. These mechanisms include the following:

- Independent and citizen oversight bodies give citizens a voice in how they are policed and in designing new ways to hold police accountable. They may operate at the local or higher levels. Oversight bodies may have a broad mandate, focus on controversial practices, or review police-citizen interactions and complaints.

- Partnerships are flexible tools that can be adapted to fit their unique context. The goal of public-police partnerships is to bring police and community organizations and individuals together in order to build trust and improve public safety. They may often be part of community-oriented policing. The partnership approach has several goals that are consonant with principles of open government — collaboration, participation, and engagement. It is the most popular type of OGP policing commitment.

- Additional accountability mechanisms, such as complaints tools, ombudsman’s offices, and improving liability regimes can improve how individuals or groups seek corrective action for mistreatment by police, for example disproportionate use of force, illegal arrest, or prolonged detention.

- Participatory budgeting is a process through which the public determines the priorities and functions of public offices. As public attention has shifted to the militarization of the police, budgeting processes have come to be seen as increasingly important in addressing crime, policing, and housing or mental health discrimination.

Across their various forms, oversight mechanisms need to be transparent in how members of the public can use them, who is a part of the decision-making, and the results of citizen input. They must have a clearly defined mandate to direct police strategies and practices. When granted such authority, oversight bodies provide a vital form of police accountability and can help ensure policing strategies reflect citizens’ needs and priorities.

Recommendations and Sample Reforms

Basic transparency

- Operating procedures: At a minimum, governments should make police operating procedures public, especially around practices such as use of force, search and seizure, and control of protests.

- Several non-governmental organizations in Eastern Europe are using Freedom of Information requests to gain access to police operating procedures.[60]

- Incident data: See the “Open Police Data” section for detailed data on incidents.

- Incident disposition data: In addition, internal investigations should make final determinations public and transparent. All presumptions should be toward disclosure, with narrow and rare cases for privacy protection. Policies that determine which data is cleared for publication should be publicly available and searchable.

Independent oversight bodies are local or higher-level bodies that give citizens a voice in how they are policed and in how police officers are held accountable.

- Practice and policy-level review

- Capacity buildingEnhancing the skills, abilities, and processes of public servants, civil society, and citizens is essential to achieving long-lasting results in opening government. Technical specifications: Set of ac...: Community panels may require advanced skills, such as data analysis and legal understanding, to best interpret appropriateness of policies. In other cases, training might be needed for facilitation, rule-setting, and documentation of decisions and notes. Community oversight bodies may have authority to review standard police operating procedures as well as practices that require additional scrutiny (e.g., use of force, search and seizure, and control of protests).

- Membership: Membership should be competitive, based on transparent criteria. Those criteria should aim for social representation, especially from groups who have historic or ongoing issues with policing and other traditionally underrepresented groups as well as those with the capacity to oversee police (such as lawyers or community organizations).

- Example: An example of a public commission to oversee a particular practice was the Stop and Search Scrutiny Panel in the West Midlands, UK. Commissions operate across each of the 10 local policing units of the region. These bodies meet independently and collectively.[61]

- Complaints and officer-citizen interaction

- Mandate: Oversight bodies at the local level may oversee issues including excessive force, harassment, discrimination, theft, and failure to provide adequate or timely police protection.

- Public complaints: Citizens can file a complaint to a citizen review board (or to internal investigative affairs) to review incidents. Barriers to do so should be low, including for individuals with few resources or low literacy. Tracking and disposition of complaints should be available to the individual.

- Review powers and authorities: Citizen oversight bodies may hold a mix of powers, including the ability to solicit, receive, consider, investigate, and publish determinations on public complaints. Such bodies need power to compel testimony and subpoena evidence to be fully effective. They should also be able to recommend various remedies, including mediation, arbitration, restoration, disciplinary action, or civil or criminal prosecution.

- Membership: Membership of such panels should be open and competitive, based on transparent criteria, which aims for social representation, especially from groups who have historic or ongoing issues with policing as well as those with the capacity to oversee police (such as lawyers or community organizations).

- Ombudsmen and citizen advocates. A special office can be created to advocate on behalf of the public. Representatives from this office may be members of an oversight body or may be independently or commission-appointed.

- Example: Newark, New Jersey’s (US) Civilian Complaint Review Board collects and investigates concerns from the public regarding the police department.[62] It also has the power to review disciplinary decisions and the department’s policies and practices.

Public-police partnerships and councils bring together police with community organizations and individuals in order to build trust and improve public safety. This may be one aspect of community policing.

- Communication and interaction: One element of community policing is having the police be present within the community and operating from a decentralized location.

- Engagement and collaboration: Police should engage with local agencies, organizations, and institutions to ensure that policing reflects community safety goals. Engagement may focus on the safety of communities that have historically experienced discrimination at the hands of police, such as migrants, racial and ethnic minorities, members of the LGBTQI+ community, people with disabilitiesA government is not open unless it is accessible to all, and governments are working to ensure people with disabilities are afforded equitable services and opportunities to participate. Technical spec..., victims of sexual assault, youthRecognizing that investing in youth means investing in a better future, OGP participating governments are creating meaningful opportunities for youth to participate in government processes. Technical ... More, or people experiencing homelessness.

- Example: In South Africa, Community Policing Forums (CPFs), composed of community members, organizations, and government authorities, monitor the effectiveness of the police and promote local police accountability.[63]

Police accountability mechanisms – these can include complaints tools, ombudsman’s offices, and other liability regimes.

- Standards and justiciability: Clear standards for policing can be laid out as part of the legal regime governing police-citizen interaction. This may cover use of force, harassment, discrimination, theft, and failure to provide adequate or timely police protection. Clear rules and procedures on standing, materiality, forums, and the cost for bringing these complaints need to be detailed, publicly available, and easily discovered.

- Civil liability: Civil liability mechanisms establish processes for remedy and redress between plaintiffs and police agencies. Actions in this area would create and enhance standards and processes and allocate resources to ensure that there is accountability for agencies that cause harm.

- Criminal liability: Jurisdictions can establish processes to make individual officers criminally liable for serious violations of the law, especially in cases of violent crime. It is also important to establish command and control responsibility for managers and senior officers for illegal orders. Finally, governments may create special offices independent of prosecutors’ offices, as prosecutors can be conflicted by their regular reliance on the police.

- Independent forums: OGP members can take steps to strengthen or establish independent forums to hear legal challenges to police operations. These will be more effective if they are independent of internal police review bodies, regular prosecutorial officers (who depend on police for investigations and prosecutions), and the executive branch. All decisions to decline or pursue charges against officers should be disclosed to the public, along with their reasoning.

Open and participatory budgeting is a process through which the public determines the priorities and functions of public offices.

- Determining allocation of services: At the time of publication, there is increasing discussion on resource allocation in the United States, specifically moving resources to conflict resolution, mental health, social work, and homelessness services. Some of this is being done through open city council meetings, as has happened with the People’s Budget[64] in Nashville, (US).[65] In other cases, participatory budgeting mechanisms have been used to discuss shifting resources, as in Los Angeles, New York, and Boston.[66]

- Including affected communities: Participatory budgeting without intentional outreach might overlook those most affected. Positive examples include communities working on responding to crime in Merseyside, UK, and working with citizens reentering the community from incarceration in Canada.[67] These can empower people at the center of police-citizen interaction.

- Ample time for public voices: An important element of participatory budgeting is that grassroots community members can speak for the majority of budget conversations. Studies show that this significantly affects the quality and outcomes. A key part of this has been the development of people’s budgets, which are budget proposals by various grassroots organizations.

There are a number of OGP commitments exclusively focused on partnerships and community-oriented policing. At this time, there are no commitments on oversight bodies (at any level), nor are there specific justice mechanisms to encourage public oversight of police actions. Examples of these mechanisms from outside of OGP are included in the previous section of this chapter (“Recommendations and Sample Reforms”).

- Afghanistan: Expand Public-Police Partnership Councils to all remaining provinces after initial success in 23 provinces (2017-2019).

- Georgia: Establish local councils composed of representatives from law enforcement, municipalities, legal organizations, and nongovernmental organizations to coordinate crime prevention measures (2016-2018).

- Panama: Create advisory councils made up of the National Police, citizen security organizations, and representatives of civil society to create and strengthen new citizen security programs (2015-2017).

- Ukraine: Train law enforcement officers in community policing practices, launch a complementary public awareness campaign, establish citizen advisory groups, create online resources for police-community coordination, and implement a “schools and police” project (2016-2018).

- Jalisco, Mexico: Create spaces for dialogue and coordination between neighborhood councils and local police in the Lomas De Polanco neighborhood in Guadalajara, Mexico, to improve citizen trust in police (2017-2019).

Guidance and Standards

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) – Handbook on Police Accountability, Oversight, and Integrity

This 2011 handbook covers a variety of internal and external mechanisms to strengthen police accountability, oversight, and integrity.[68] Specifically, the report offers recommendations regarding complaints against the police, independent oversight and complaint bodies, internal accountability, accountability to the state, and engaging the public. It is based on international standards and practices.

UNODC and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) – Resource Book on the Use of Force and Firearms in Law Enforcement

The 2017 UNODC and OHCHR Resource Book on Use of Force and Firearms in Law Enforcement[69], which builds on international human rights law and the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms, covers the international legal framework, a human-rights approach to policing, the responsibility of law enforcement (command and control and human resources management), instruments of force, policing situations, and accountability for use of force and firearms.

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights – New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing

This 2019 US report includes recommendations on community policing, responding to crises, the US First Amendment and free speech, accountability, and police data.[70]

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

OSCE offers guidebooks on Good Practices in Building Police-Public Partnerships (2008),[71] Democratic Policing (2007),[72] and Human Rights Education for Law Enforcement Officials (2012).[73] In particular, the Guidebook on Democratic Policing highlights the role of various types of oversight institutions in police accountability, including the functions of internal and public oversight mechanisms (sections 84-94).

The National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement -“What are the features of an effective police oversight body?”

NACOLE (US) recommends several key features for effective public oversight, including sufficient independence, funding, authority, access to information and decision-makers, transparency, and community outreach.[74]

US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

The 2019 Law Enforcement Best Practices: Lessons Learned from the Field report provides guidance for implementing a community policing approach.[75] The 2009 Standards and Guidelines for Internal Affairs: Recommendations from a Community of Practice focuses on internal complaint review and resolution processes.[76]

Human Rights Watch – Shielded from Justice: Police Brutality and Accountability in the United States

This 1999 report investigates patterns of police abuse and accountability across 14 American cities.[77] It highlights obstacles to successful civil and criminal lawsuits regarding police misconduct.

Police – Resources and Partners

Resources

Global

- The Centre for Human Rights and the Institute for International and Comparative Law in Africa at the University of Pretoria publishes The Law on Police Use of Force Worldwide, an index of national and international policing laws.

- The Institute for Security and Democracy (Instituto para la Seguridad y la Democracia) report, Transparency: Pathway to Effective and Legitimate Public Policing (Transparencia: Ruta para la Eficacia y Legitimidad en la Función Policial), offers recommendations for police transparency.

Europe

- The Open Society Justice Initiative’s Reducing Ethnic Profiling in the European Union: A Handbook of Good Practices provides recommendations to address racial profiling by police in the EU.

United States

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights’ New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing provides recommendations on handling data and video footage among other topics.

- US General Services Administration, Office of Evaluation Sciences’ 2016 Community Action Deck: A discussion support tool for empowering communities to take action on the recommendations of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing outlines actions community reformers can take to further implementation of recommendations from the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

- Campaign Zero lists policy recommendations for community oversight of police and provides several databases aggregating and visualizing relevant police data:

- Use of Force Project aggregates data on use of force policies across the United States, including comprehensive reporting requirements.

- California Police Scorecard Project grades police agencies based on several indicators, including police accountability and civilian complaint outcomes.

- Mapping Police Violence aggregates data on police-involved killings along with whether the officer was charged with a crime.

- Olugbenga Ajilore offers concrete recommendations in the article “How Civilian Review Boards Can Further Police Accountability and Improve Community Relations.”

- The Opportunity Agenda provides recommendations regarding various mechanisms for police accountability.

- The American Civil Liberties Union’s Fighting Police Abuse: Community Action Model provides action-oriented guidance for community reformers.

Organizations

- African Police Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF)

- Center for Policing Equity (United States)

- Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI)

- Igarapé Institute (Latin America)

- Instituto para la Seguridad y la Democracia (insyde) (Mexico)

- Instituto Sou da Paz and Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública (Brazil)

- Campaign Zero (United States)

- National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement (United States)

- National Initiative for Building Community Trust & Justice (United States)

- The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

- Open Society Foundations

- Vera Institute of Justice (United States)

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

Prosecutors

Overview

Overview

Given their often far-reaching authority and discretion, prosecutors’ decisions can shape a variety of trends in the criminal justice system. In addition to their role in determining which cases to prosecute, in some jurisdictions, prosecutors may also investigate crimes or supervise investigators, dictate bail and plea agreements, determine which cases are diverted to alternatives to prosecution, and influence sentencing decisions.[78] Often, this work occurs outside of the public eye to protect prosecutors’ independence and integrity. However, in at least some countries, this lack of transparency has contributed to problematic trends, such as mass incarceration,[79] disproportionate effects of prosecution on minority communities,[80] and executive capture of public prosecutors.[81]