Mongolia Results Report 2021-2023

- Action Plan: Mongolia Action Plan 2021-2023

- Dates Under Review: 2021-2023

- Report Publication Year: 2024

Mongolia’s fourth action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... opened access to usable information on public procurementTransparency in the procurement process can help combat corruption and waste that plagues a significant portion of public procurement budgets globally. Technical specifications: Commitments that aim t... More and government services, as well as strengthening access to information legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r.... The national OGP platform offered little oversight or coordination with civil society or government commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... holders but began to course correct during the final six months of the implementation period. By building government ownership of commitments and consistent collaboration with civil society, Mongolia could achieve more meaningful outcomes from the OGP process.

Early ResultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More

Early ResultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More

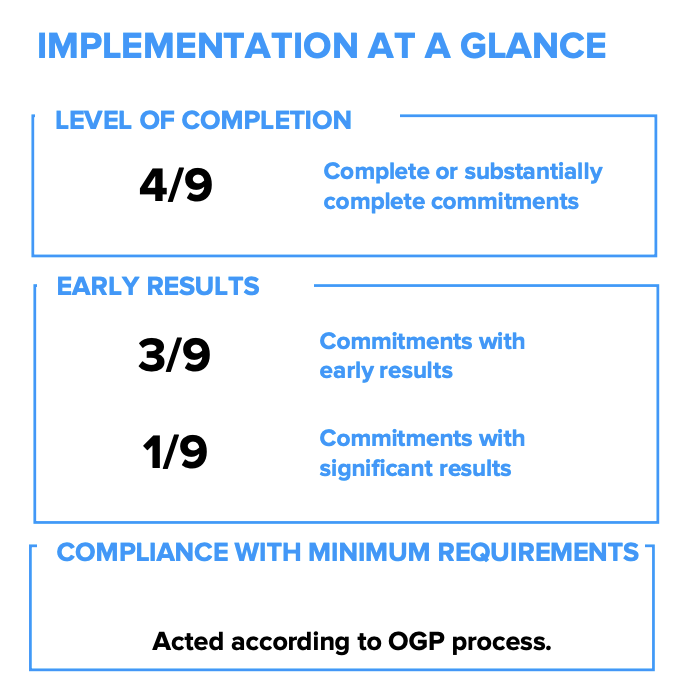

Three of the action plan’s nine commitments produced early results, primarily opening access to government information. Commitment 3 achieved significant results, building on previous action plans’ progress to integrate government procurement systems, improve the online tender portal, and launch an open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici... portal for tender information. Two commitments moderately improved access to information legislation (Commitment 2) and practical information about government services available on the E-Mongolia and newly launched E-Business platforms (Commitment 9). The action plan’s other six commitments did not produce notable early results, struggling with implementation obstacles, including three of the five commitments that IRM identified as having the potential to realize the most promising results at the design phase. Overall, this action plan had better results than the previous action plan, in which only one commitment had marginal results on opening government.

CompletionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More

Four of the action plan’s nine commitments (44%) were substantially or completely implemented (2, 3, 6, and 9), most of which produced early results in opening government. This was a slightly higher implementation rate than the previous action plan, in which 4 of 13 commitments (31%) were substantially or completely implemented. With little oversight or coordination from Mongolia’s OGP platform, commitments that made progress were often instead linked to wider government priorities. The initiatives’ inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More in OGP commitments was not the key motivation for their implementation. For instance, Commitment 6 shared goals with existing World Bank projects. Commitments 2 and 3 were buoyed by government’s heightened focus on anti-corruption measures amid intense public demand following national scandals. Implementation of the action plan’s other commitments faced challenges, including high stakeholder turnover, lingering effects of the pandemic, and geopolitical crisis. A breakdown in civil society engagement left significant gaps in resources and support for commitments’ delivery. Promising commitments on protecting civic space and freedom of the press (4 and 8) did not see substantial progress, leaving a continued need for Mongolia’s open government process to address these reforms.

Participation and Co-Creation

Mongolia met the OGP threshold for participation during the co-creation and implementation phases, as compared to the previous two action plans when Mongolia was found to be acting contrary to OGP process. Co-creation saw slight improvements in participation, including the provision of reasoned responseOngoing dialogue between stakeholders during the development of an OGP action plan is critical to the plan’s success. Specifically, communicating back to stakeholders the ideas received and decision... to the public on how their contributions were considered during development of the action plan. During most of the implementation period, there was virtually no oversight over commitment progress, engagement across the bureaucracy on the action plan, or coordination between government and civil society stakeholders through Mongolia’s OGP platform. The OGP coordination role shifted from the Cabinet Secretariat to the Ministry of Economy and Development to the National Committee for Human RightsAn essential part of open government includes protecting the sacred freedoms and rights of all citizens, including the most vulnerable groups, and holding those who violate human rights accountable. T... (NCHR) under the Cabinet Secretariat. Cabinet reshuffles affecting the Ministry of Mining and Heavy Industry, the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, and the Ministry of Digital Development and Communications exacerbated coordination gaps, as the ministries were responsible for multiple commitments. During the final six months of implementation, NCHR began to course correct, with newly appointed members of the OGP National Council meeting twice in July and August 2023, followed by the publication of an action plan implementation self-assessment report on Mongolia’s OGP repositoryAccess to relevant information is essential for enabling participation and ensuring accountability throughout the OGP process. An OGP repository is an online centralized website, webpage, platform or ....

Implementation in Context

In addition to government turnover, implementation of Mongolia’s action plan faced geopolitical and domestic challenges. As a landlocked country, Mongolia is significantly impacted by developments in China and Russia, its two neighboring countries. China is responsible for more than 60% of Mongolia’s total trade.[1] As China implemented its zero-COVID policy, consumer products became scarce, and inflation rates soared from 1.9% in 2020 to 3.5% in 2021 and 8.3% in 2022.[2] Amid the war in Ukraine, Mongolia also faced pressure to balance between sustaining political independence and reliance on Russia—whose banks facilitate most of its foreign trade and whose energy companies provide nearly all of its oil.[3] Meanwhile, despite easing COVID-19 restrictions in the later stage of the implementation period, their impact meant that the government had to prioritize economic measures and could not allocate a budget to support action plan implementation. In addition, government corruption continued to erode public trust. A corruption scandal involving state-owned enterprises triggered weeks-long public protests at the end of 2022. This also led to a heightened focus on anti-corruption measures progressed by some of the action plan’s commitments. Meanwhile, the operating environment for civil society continued to be a challenge, defined by CIVICUS as “narrowed.”[4]

Key Observations

This section highlights three key observations on Mongolia’s fourth action plan cycle. These observations address the leadership of the OGP process, wider government priorities’ influence on commitment implementation, and weak coordination with civil society. Altogether, the following observations imply that through stronger collaboration with civil society, the government could achieve more meaningful outcomes from the OGP process.

Observation 1: Meaningful collaboration on OGP works best with stable government ownership and a well-resourced multi-stakeholder framework. After the co-creation phase, the initial OGP lead agencies were often inactive, and the OGP platform lost momentum. Commitment delivery was not monitored regularly, and leadership changes among implementing agencies limited engagement with civil society. Since becoming the lead agency in March 2023, National Committee for Human Rights (NCHR) began to course correct—facilitating the only OGP National Council meetings in the action plan cycle and collecting commitment implementation reports from lead agencies. However, these improvements came during the last months of implementation. Ahead of the next action plan’s co-creation processCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders (e.g., citizens, academics, private sector) is at the heart of the OGP process. Participating governments must ensure that a dive..., NCHR convened a meeting with the civil society stakeholders that have been strong partners since Mongolia became an OGP member. It is important to sustain this momentum through the implementation of the next action plan, beyond the co-creation phase. This will require providing NCHR and the OGP National Council with sufficient national budget funding and resources, which could be ensured by providing a legal basis for funding and mandate. Additionally, leadership of the multi-stakeholder process can be shared between government and civil society stakeholders, with clearer rules of engagement.

Observation 2: Wider government priorities determine commitment implementation. The commitments that achieved at least a substantial level of completion and generated at least moderate early results in this action plan were all built on wider government priority agendas. Commitments 3, for example, achieved significant results due to Mongolia’s heightened focus on strengthening anti-corruption measures amid intense public demand for the government to root out corruption following national scandals. Conversely, commitments not specifically aligned with government priorities did not generate early results. Commitment 4 failed to complete any of its milestones despite being assessed as promising in the Action Plan Review, mostly due to inaction from the government and pushback from civil society over concerns that it could add barriers for CSOs to operate legally. Likewise, Commitment 7 was not perceived as a top government priority, and implementation was limited.

Observation 3: Public demand contributes to results. Because Mongolia’s OGP platform lost momentum during implementation, most of the milestones that were not delivered were ones that required active participation from civil society. For instance, legislative amendment and policy evaluation in Commitments 4 and 5 were not fully completed, partly due to lack of support from civil society and the public. However, for the commitments with stronger early results, wider public demand notably incentivized the government to take action. Strong public support via an online petition to strike down the social network control law led to a presidential veto. A significant increase in the number of active users of the E-Mongolia platform under Commitment 9 influenced the government to invest in making the platform more accessible. The next action plan could identify specific commitments that would benefit from linking wider public engagement to certain steps in policy-making, in addition to consultation with civil society representatives. For example, in cases where stakeholders have struggled to achieve regulatory reforms, generating public demand could potentially help make notable improvements (through tools such as online petitions or open public consultations).

[1] Antonio Graceffo, “Mongolia Suffers Under China’s Zero-Covid Policy,” The Lowy Institute, 19 January 2022, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/mongolia-suffers-under-china-s-zero-covid-policy.

[2] “Inflation, Consumer Prices (annual %), Mongolia,” The World Bank, accessed 20 August 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG.

[3] David Stanway, “Mongolia’s East-West Balancing Act Buffeted by Russian Invasion of Ukraine,” Reuters, 3 March 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/mongolias-east-west-balancing-act-buffeted-by-russian-invasion-ukraine-2022-03-03.

[4] CIVICUS, People Power Under Attack 2023, 2023, https://civicusmonitor.contentfiles.net/media/documents/GlobalFindings2023.pdf.

Leave a Reply