Papua New Guinea Results Report 2022–2024

- Action Plan: Papua New Guinea Action Plan 2022-2024 (June)

- Dates Under Review: 2022-2024

- Report Publication Year: 2025

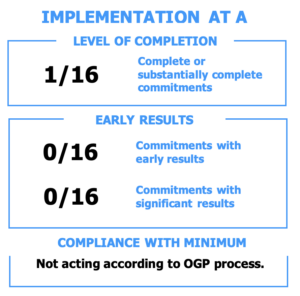

Papua New Guinea’s second action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... made progress on digital government reforms. While none of the other commitments were completed during the implementation period, continued efforts may produce open government results in the longer term. Collaboration between government and civil society was limited during co-creation and implementation of the action plan.

Early results

While there were steps to improve access to government services, none of the action plan’s 16 commitments yielded early results. Commitments 7 and 8 launched the PNG E-Government Portal[1] and passed the Digital Government Act 2022[2] and Digital Government Plan 2023–2027[3], but have not yet widened access to government information. CommitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 4 held regional budget consultations with the public. However, their recommendations had yet to be implemented. Continued efforts may produce open government results in the longer term.

Overall, most commitments had limited completion during the implementation period, which in turn limited early results. This included Commitments 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, and 12 which the IRM noted as promising in the Action Plan Review. In particular, commitments to publish annual audit reports (5) and pass an Access to Information Act (6) did not achieve their objectives. These are central to Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) ability to meet OGP’s core eligibility criteria moving forward[4].

Completion

Compared to the previous action plan, which was implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, a higher proportion of commitments saw some progress – although implementation continued to face obstacles. Commitment 8 on the digital government legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r..., policy, and strategy was completed. Eleven other commitments saw limited implementation, while four were not started during the implementation period. There was little oversight of implementation progress with infrequent National Steering CommitteeThe Steering Committee is OGP’s executive decision-making body. Its role is to develop, promote and safeguard OGP’s values, principles and interests; establish OGP’s core ideas, policies, and ru... meetings and an OGP secretariat that was interim rather than permanent. Common implementation challenges included inadequate funding, insufficient capacity, and misaligned priorities between implementing agencies and action plan objectives. To illustrate, despite a legislative basis for establishing youthRecognizing that investing in youth means investing in a better future, OGP participating governments are creating meaningful opportunities for youth to participate in government processes. Technical ... More networks in subnational governments, implementers of Commitment 1 were left without sufficient resources to achieve this objective, as recruitment for relevant subnational government positions was halted.

However, even after the action plan ended in June 2024, stakeholders continued work on outstanding elements of the commitments. This positive effort led to launch of the PNG E-Government Portal (Commitment 7) and validation workshops on the Government-CSO Partnership Policy (Commitment 2) and Informal Economy Voice Strategy (Commitment 3) by the end of 2024, outside the implementation period under review. In 2025, the Planning and Monitoring Responsibility Act is expected to be enacted (Commitment 9).

Participation and co-creation

The Department of National Planning and Monitoring managed the OGP process in PNG alongside TransparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More International Papua New Guinea (TIPNG), with support from an interim secretariat. The National Steering Committee, Papua New Guinea’s OGP multistakeholder forum, consisted of the government agencies and civil society organisations involved in the action plan’s commitments. Compared to the previous action plan, civil society participation in co-creation improved, though consultation was limited by a tight timeframe and COVID-19 restrictions. Each cluster of commitments was co-led by a government agency and a civil society organisation to ensure collaboration. However, participation during implementation declined, as the National Steering Committee held few meetings. PNG launched its first OGP website in 2023, although there were delays in keeping it updated.

Over the course of the action plan cycle, Papua New Guinea did not meet the minimum requirements of the OGP Participation and Co-Creation Standards[5]. During co-creation, basic rules on the multistakeholder forum were not publicly available. The website and repositoryAccess to relevant information is essential for enabling participation and ensuring accountability throughout the OGP process. An OGP repository is an online centralized website, webpage, platform or ... had not yet been published and stakeholder contributions were not documented or provided with reasoned responseOngoing dialogue between stakeholders during the development of an OGP action plan is critical to the plan’s success. Specifically, communicating back to stakeholders the ideas received and decision... prior to the action plan’s publication. During implementation, the multistakeholder forum did not meet every six months. Its basic rules were still not publicly available and the repository did not publish information on co-creation or implementation of the action plan. OGP instituted a 24-month grace period to ensure a fair and transparent transition to the updated standards, extending to 31 December 2023. As this action plan was co-created and submitted in 2022, it falls within the grace period. Under the previous action plan, PNG was found to be acting contrary to OGP process, having not published a repository in line with IRM guidance.

Implementation in context

During the implementation period, Papua New Guinea’s politics were marked by frequent ministerial reshuffles, resignations, and shifting allegiances between the government and opposition. Elections led to the formation of a new government in August 2022. In May 2024, the Minister for National Planning and Monitoring resigned from the government and joined the opposition. The opposition nominated him to challenge the prime minister in a vote of no confidence, along with five other such attempts in 2024[6].

There continued to be government support for OGP, but this political volatility affected the implementation of commitments. During the election period and formation of the new government, focus shifted away from OGP. When ministers were reshuffled, new appointees often brought in different priorities for their agencies, disrupting commitments’ progress. There were concerns over politicisation of PNG’s bureaucracy, which impacted the efficiency and independence of state agencies[7]. Additionally, concerns have been raised about the increased risk of corruption and bribery as government and opposition sought to secure political support, particularly during the votes of no confidence[8]. This undermined efforts to open government[9]. The audit reports pursued by Commitment 5, for instance, could only be published if tabled in parliament – But the possibility of audits revealing illegal payments disincentivised parliamentarians[10].

[1] ‘Papua New Guinea Gavman Portal,’ Gavman, accessed 6 January 2025, https://www.gavman.gov.pg/dashboard.

[2] ‘Digital Government Act 2022,’ Department of Information and Communications Technology, https://www.ict.gov.pg/digital-government-act-2022.

[3] ‘Digital Government Plan 2023–2027,’ Department of Information and Communications Technology, https://www.ict.gov.pg/Digital%20Govt%20Plan%202023-2027/Digital%20Government%20Plan%202023-2027%20-%20Final%20Version.pdf.

[4] ‘Papua New Guinea – Eligibility Review Letter,’ Open Government Partnership, June 2023, https://www.opengov partnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Papua-New-GuineaEligibility-Review-Letter_20230630.pdf.

[5] ‘OGP Participation and Co-Creation Standards,’ Open Government Partnership, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/ogp-participation-co-creation-standards.

[6] Michael Kabuni, ‘Marape defeats vote of no confidence: What next?’ Dev Policy of Australian National University, 13 September 2024, https://devpolicy.org/marape-defeats-vote-of-no-confidence-what-next-20240913.

[7] R. J. May, ‘State and Society in Papua New Guinea, 2001–2021,’ Australian National University Press, 2022, https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n10184/html/ch02.xhtml.

[8] Michael Kabuni, Maholopa Laveil, Geejay Milli, and Terence Wood, ‘Elections and Politics,’ in: ‘Papua New Guinea: Government, Economy and Society,’ Stephen Howes and Lekshmi N. Pillai (eds.), Australian National University Press, 2022, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/53657/book.pdf?sequence=1#page=33; Kabuni, ‘Marape defeats vote of no confidence: What next?’

[9] Consultative Implementation and Monitoring Council, interview by the IRM, 6 August 2024.

[10] Auditor General’s Office, interview by the IRM, 29 August 2024.

Leave a Reply