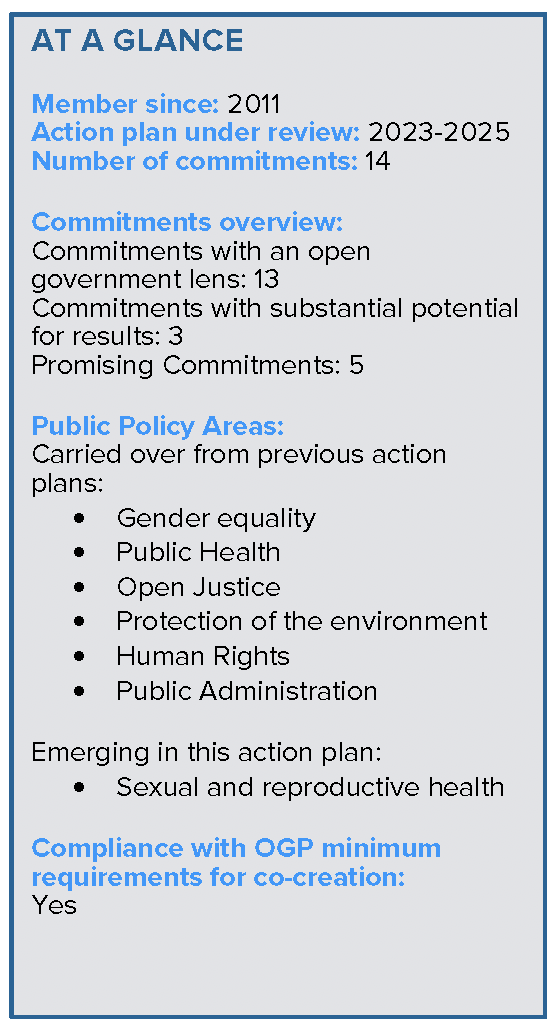

Peru Action Plan Review 2023-2025

- Action Plan: Peru Action Plan 2023-2025

- Dates Under Review: 2023-2025

- Report Publication Year: 2024

Peru’s fifth action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... is notable for the participation of the multi-stakeholder forumRegular dialogue between government and civil society is a core element of OGP participation. It builds trust, promotes joint problem-solving, and empowers civil society to influence the design, imple... created in 2020 and the involvement of new civil society actors. The plan includes commitments from all three branches of the state. However, there remains an opportunity to increase the ambitionAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should “stretch government practice beyond its current baseline with respect to key areas of open government.” Ambition captures the po... of these commitments. Many proposals still focus solely on creating access to information tools. Additionally, the activities lack clear indications of added value for this new cycle.

Peru’s fifth action plan has 13 commitments divided into five thematic areas: environment, health, education, justice, and open parliament. The multi-stakeholder forum, whose operations started in 2020, chose the five prioritized themes which were later validated through public citizen consultation[1]. Four themes come from previous action plans, and one, open parliamentEnsuring access to legislative information and creating mechanisms for public participation are critical to building an open, trusting relationship with citizens. Technical specifications: Commitments... More, is the first collaboration of the Peruvian Congress in the OGP process.

Peru’s fifth action plan has 13 commitments divided into five thematic areas: environment, health, education, justice, and open parliament. The multi-stakeholder forum, whose operations started in 2020, chose the five prioritized themes which were later validated through public citizen consultation[1]. Four themes come from previous action plans, and one, open parliamentEnsuring access to legislative information and creating mechanisms for public participation are critical to building an open, trusting relationship with citizens. Technical specifications: Commitments... More, is the first collaboration of the Peruvian Congress in the OGP process.

The action plan’s design process established four stages for the participation of interested parties: preparatory activities, problem discussion, “brainstorming” and co-creation. The multi-stakeholder forum selected the topics to be addressed as part of the preparatory activities. Thirteen civil society organizations prepared 34 diagnoses[2] that based the discussions on the specific problems and the solutions that the action plan could provide through commitments[3]. Civil society organizations[4] and state representatives participated in the problem discussion, brainstorming, and co-creation workshops. Subsequently, a public citizen consultation validated the draft commitments prepared by state representatives[5]. Unlike previous processes, it is regarded as positive that the design of the new action plan has sought the prominence of interested parties throughout the entire co-creation processCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders (e.g., citizens, academics, private sector) is at the heart of the OGP process. Participating governments must ensure that a dive... and not only in the initial stages.

The civil society organizations represented in the multi-stakeholder forum considered that the co-creation cycle was transparent to the interested parties: the forum members received the calendar of activities, and new civil society organizations participated. However, they also mention that the process was rushed at times, with very short deadlines[6] or days of several parallel meetings[7], which prevented systematic monitoring of the process. Also, they point out that the commitments are not sufficiently ambitious, as several of them do not exceed the current ministries functions destined to generate distinctive results within this action plan.

Aspects that could have contributed to a better process include having more participants[8], working on cross-cutting issues[9] or escalating to new approaches[10], and involving senior officials from the ministries[11] (such as planning directors or policy directors).

The Government considers that the involvement of civil society reached more substantial levels than in previous plans, given its participation in the initial selection of prioritized themes, in the creation of diagnoses, and in the validation of the co-created commitments. However, the Government also recognizes problems in meeting the deadlines to comply with all the proposed stages, an issue related to the use virtual meetings in the post-COVID-19 context, and political instability[12].

From the commitments’ review, the IRM finds that most have modest potential (9 of 13), followed by three commitments of uncertain potential and one with substantial potential for results. Commitments of modest potential are characterized by generating new tools to facilitate access to information (typically websites, apps, or QR) or publication of data, but without generating binding or institutionalized changes in the Government or in the institutions that handle public policies. Commitments 8, 9, and 10 (health), 4, 5, and 7 (educationAccountability within the public education system is key to improving outcomes and attainment, and accountability is nearly impossible without transparent policies and opportunities for participation ...), 12 (JudiciaryWhile a majority of open government reforms occur within the executive branch, OGP members are increasingly taking on commitments to increase the openness of the judicial branch. Technical specificati...), and 13 (Congress of the Republic) generate positive steps toward openness but do not transcend the creation of tools or improve access to information.

The commitments of uncertain potential have unclear changes to existing practices associated with their implementation. Such is the case of those reprised from previous action plans: commitments 2 and 3 (environment) and 11 (public insurance of the health sector), also included in the third action plan. The Government points out that the eventual lack of ambition is because the entities had to align the commitments with their internal budgetary, operational, and strategic planning[13].

Among the strengths of the action plan are the multi-stakeholder forum’s involvement in the co-creation process of the fifth plan and the inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More of civil society through innovative mechanisms, such as creating diagnoses that inform the commitments’ co-creation process. Regarding commitments, commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 1 “Review and improve the regulatory framework of the National Environmental Impact Assessment System (SEIA, per its acronym in Spanish) concerning the application of citizen participationAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, citizen participation occurs when “governments seek to mobilize citizens to engage in public debate, provide input, and make contributions that lead to m... More mechanisms” stands out as promising, as it opens the possibility for a systematic application of citizen participation mechanisms in those sectors where the law requires the application of environmental impact assessment mechanisms. Similarly, commitment 6 to “promote the implementation of spaces for student participation in educational institutions of regular and alternative basic education”, also aims to generate regulatory changes that facilitate and promote citizen participation in schools.

[1]https://www.gob.pe/22440-consulta-publica-para-definir-los-temas-del-v-plan-de-accion-de-gobierno-abierto The Government provided descriptions (extracted in .xlsx from the Peruvian State consultation site “Facilita”) of the participation in the May public consultation: 44 people contributed.

[2] Although the action plan mentions 34 diagnoses, the researcher had access to 15 diagnoses carried out by Bartolomé de las Casas Center, Academic Network of Open Government and Grade on Education, DAR, and SPDA on the environment, Academic Network of Open Government, Vigilia Ciudadana and SPDA on JusticeTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi..., Roche on Health; and APROSEC and Universidad del Pacífico on Citizen Security, in addition to diagnoses carried out by international cooperation entities and Government actors.

[3] Action Plan, p. 7-12. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Peru_Action-Plan_2023-2025.pdf According to the action plan, civil society organizations, academia, the private sectorGovernments are working to open private sector practices as well — including through beneficial ownership transparency, open contracting, and regulating environmental standards. Technical specificat... More, and international cooperation prepared the diagnoses. The IRM researcher had access to the diagnosis on environmental matters prepared by the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law (SPDA, per its acronym in Spanish).

[4] According to Jimena Sánchez Velarde, USAID representative in the process, there was a limited number of civil society representatives at the Education and Health tables, where she participated.

[5]https://facilita.gob.pe/t/3201 The Government provided descriptions (extracted in .xlsx from the Peruvian State consultation site “Facilita”) of the participation in the May public consultation: 22 people contributed.

[6] Interview with Pámela Ramírez, SPDA representative, May 4, 2023.

[7] Interview with Mela Salazar, Vigilia Ciudadana representative, May 10, 2023.

[8] Interview with Ramiro Rodrich, Roche Perú representative, May 5 2023; Interview with Jimena Sánchez Velarde, USAID representative in the process.

[9] Interview with con Mela Salazar. May 10, 2023

[10] Interview with Pámela Ramírez. May 4, 2023.

[11] Interview with Lourdes Febres, Acción por los Niños representative, August 15, 2023.

[12] Interview with Sebastián Rivera, Government point of contact, April 24, 2023.

[13] Action Plan Review 2023-2024 comments, p. 22.

Leave a Reply