Philippines Action Plan Review 2023-2027

- Action Plan: Philippines Action Plan 2023-2027 (December)

- Dates Under Review: 2023-2027

- Report Publication Year: 2024

The Philippines’ sixth action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... intends to open large government infrastructure projects to public monitoring and progress local-level access to justiceAccessible justice systems – both formal and informal – ensure that individuals and communities with legal needs know where to go for help, obtain the help they need, and move through a system tha... More and freedom of information efforts. Its commitments could go further to take advantage of the new four-year implementation period. Political transitions delayed the co-creation processCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders (e.g., citizens, academics, private sector) is at the heart of the OGP process. Participating governments must ensure that a dive..., but multi-stakeholder engagement remained high, and an executive order institutionalized expansion of the multi-stakeholder forumRegular dialogue between government and civil society is a core element of OGP participation. It builds trust, promotes joint problem-solving, and empowers civil society to influence the design, imple....

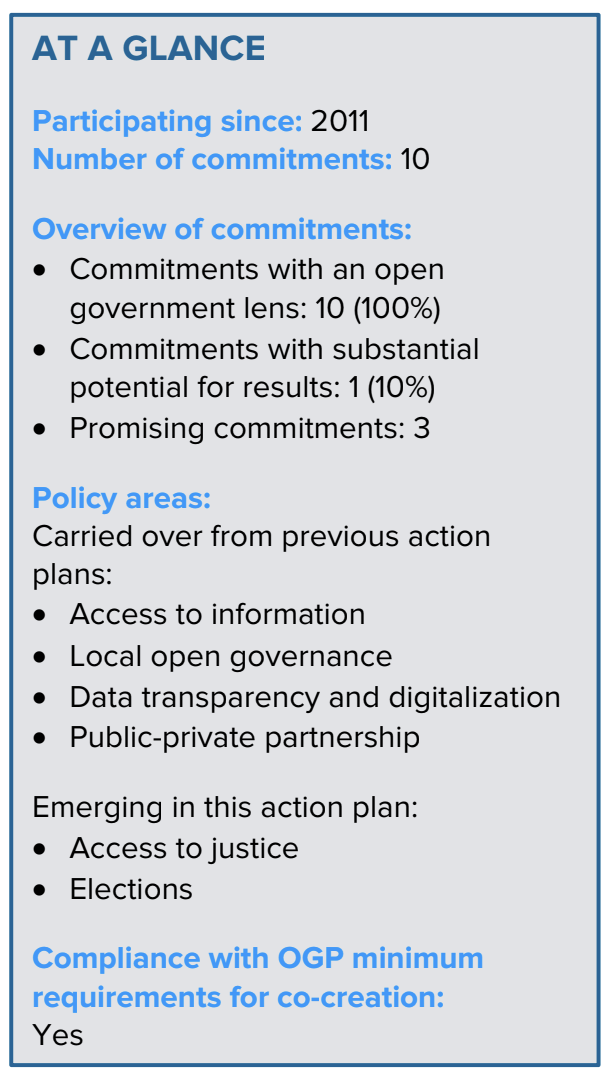

This report evaluates the design of the Philippines’ sixth action plan, its first to span a four-year implementation period. Among its ten commitments, expanded engagement with broader government agencies led to new efforts on access to justiceTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi..., electionsImproving transparency in elections and maintaining the independence of electoral commissions is vital for promoting trust in the electoral system, preventing electoral fraud, and upholding the democr... More, and Sustainable Development GoalsOGP countries are experimenting with open government innovations to accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 16+ which includes peaceful, just and inclusive societies... (Commitments 2A, 2B, 4A, 4B, 5, and 8). Some of its other commitments carry over focus areas from the previous action plan, such as promoting access to information, enabling data transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More and digitalization, opening participation in local governance, and strengthening public-private partnership in development (Commitments 1, 3, 6, and 7). The action plan includes a cross-cutting focus on localizing open government efforts (Commitments 1, 2A, 7, and 8). The OGP process is led by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM), and its new Secretary showed greater support for PH-OGP.

This report evaluates the design of the Philippines’ sixth action plan, its first to span a four-year implementation period. Among its ten commitments, expanded engagement with broader government agencies led to new efforts on access to justiceTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi..., electionsImproving transparency in elections and maintaining the independence of electoral commissions is vital for promoting trust in the electoral system, preventing electoral fraud, and upholding the democr... More, and Sustainable Development GoalsOGP countries are experimenting with open government innovations to accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 16+ which includes peaceful, just and inclusive societies... (Commitments 2A, 2B, 4A, 4B, 5, and 8). Some of its other commitments carry over focus areas from the previous action plan, such as promoting access to information, enabling data transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More and digitalization, opening participation in local governance, and strengthening public-private partnership in development (Commitments 1, 3, 6, and 7). The action plan includes a cross-cutting focus on localizing open government efforts (Commitments 1, 2A, 7, and 8). The OGP process is led by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM), and its new Secretary showed greater support for PH-OGP.

The IRM identified three commitments as promising. CommitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 3 intends to launch a digital portal with real-time information on large government infrastructure projects, along with a public feedback mechanism to facilitate citizen monitoring and oversight of the projects’ implementation. Commitment 1 continues to target passage of a national Freedom of Information Law but focuses on scaling up freedom of information efforts at the local level. Its success will rely on fully pursuing both national and local reform, without allowing one to replace the other. Commitment 2A is one of the Philippines’ first OGP commitments on access to justice, offering progress on existing government efforts to expand the Justice Zones program, in which localities enhance police, prosecutors, courts, and prisons’ coordination on access to justice.

In June 2023, the government issued Executive Order No. 31, which institutionalized the expansion of the PH-OGP multi-stakeholder forum.[1] It broadened non-government representation to include civil society organizations (CSOs) representing women and youth and added thematic experts on issues such as environment and justice.[2] The order also mandated formal terms of reference, as well as dedicated staffing and financial resources.[3] Members of the new steering committeeThe Steering Committee is OGP’s executive decision-making body. Its role is to develop, promote and safeguard OGP’s values, principles and interests; establish OGP’s core ideas, policies, and ru... were onboarded in February 2024 after the action plan had already been finalized.

The co-creation timeline was approved in late 2022, but public consultations did not commence until mid-2023.[4] There was less preparatory work on engagement between civil society and government commitment holders than in the previous cycle.[5] The secretariat opened a call for commitment proposals in February–June 2023. This process was guided by an Agenda for Good Governance developed by the PH-OGP non-government secretariat and vetted by over 100 CSOs. It identified anti-corruption, protection of civic space, and access to justice as priority areas.[6] Civil society saw it as a useful advocacy framework but felt there could have been more opportunities to align its priorities and the commitment proposals.[7] During August through October, a consultation was organized in each of the major islands or regions and the national capital region, reaching over 305 participants,[8] along with one for youth.[9] In some cases, challenges included travel costs,[10] lack of prior familiarity with the policy areas discussed,[11] and a short time allocation for civil society feedback on each commitment.[12] However, broadened involvement of government agencies and CSOs resulted in a record 27 commitment proposals submitted by 21 agencies.[13] A November workshop with experts refined 14 shortlisted proposals.[14] Interviewed stakeholders considered this the most productive co-creation workshop and noted that this approach would have benefited earlier stages. Later that month, the PH-OGP steering committee reviewed the final design of commitments. Another two-week online public comment period was opened before the action plan was finalized in December.[15] Overall, face-to-face regional consultations and expert-guided workshops provided more dynamic and focused spaces for commitment design than the previous co-creation process. Representatives of the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) noted that mechanisms for giving, receiving, and responding to feedback could be improved.[16]

A civil society stakeholder described the final result as a “recovery action plan.” Commitments were largely determined by feasibility considerations, with little room for innovation beyond existing government projects,[17] and were prioritized based on relevance to the Marcos administration’s Philippine Development Plan.[18] Several commitments replicate ongoing initiatives. For instance, Commitment 7 continues subnational activities to engage stakeholders to participate in resource governance, while Commitment 8 does not go beyond the established framework for progressing the Sustainable Development Goals, and some of its milestones were completed before the implementation period. Some commitments also overlook the root causes of their policy problems—as with Commitment 4A, which intends to accredit CSOs to verify and certify voters lists, but does not address capacity constraints among election officers, local civil registrars, and courts of justice. Given the four-year implementation period, to achieve lasting open government results, the IRM recommends revisiting the commitments’ targets during the midpoint refresh process.

Additionally, the steering committee put 13 commitment proposals onto a “waiting list”[19] that could be adopted during the refresh process. To raise these proposals’ ambition levels in the interim, they intend to provide opportunities for the proposers to “incubate” their ideas, with support for improvement, exposure to learning opportunities, and access to relevant resources.[20] This showcases the PH-OGP secretariat’s strategic approach to the new action plan timespan, aiming to retain the interest of stakeholders who might otherwise disengage from this OGP cycle.

Overall, amid recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, two divisive national elections, political transitions, and shrinking civic space, both government and non-government stakeholders involved in the co-creation process were unable to contribute to their maximum capacity.[21] Going forward, the DBM will establish a PH-OGP Project Management Office (PMO) to orient new personnel, potential commitment holders, and stakeholders on OGP practices and standards. In the longer term, leveraging the expertise and experience of the new steering committee representatives can attune the commitments to the needs of a broader constituency.

Promising Commitments

The following review looks at the three commitments that the IRM identified as having the potential to realize the most promising results. Promising commitments address a policy area that is important to stakeholders or the national context. They must be verifiable, have a relevant open government lens, and have modest or substantial potential for results. This review also provides an analysis of challenges, opportunities, and recommendations to contribute to the learning and implementation process of this action plan.

Table 1. Promising commitments

| Promising Commitments |

| 1. Localizing the freedom of information program: This commitment continues efforts to pass a national legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r... and local ordinances on freedom of information and onboard government institutions onto the e-FOI portal. |

| 2A. Expanding and enhancing Justice Zones: This commitment intends to pass national legislation or local ordinances to institutionalize support for Justice Zones or localities that commit to enhance police, prosecutors, courts, and prisons coordination on access to justice. It also plans to continue expanding the number of Justice Zones nationwide. |

| 3. Leveraging digital information to monitor and evaluate infrastructure projects: This commitment plans to relaunch a portal that will open the public’s ability to monitor and evaluate big-ticket government infrastructure projects. |

[1] Executive Order No. 31, “Institutionalizing the Philippine Open Government Partnership and for Other Purposes,” Malacañang Palace, (20 June 2023), https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2023/06/20/executive-order-no-31-s-2023.

[2] Executive Order No. 31.

[3] Claire Bautista (Department of Budget and Management/PH-OGP Government Secretariat), interview by IRM researcher, 5 February 2024; Sandino Soliman (Caucus of Development NGO Networks/PH-OGP Non-Government Secretariat), interview by IRM researcher, 1 March 2024.

[4] “The 6th NAP Development Schedule,” PH-OGP Government Secretariat, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1YlRkyPrR2CHTBjlVgQBZhKbBcW0_1_PW.

[5] Soliman, interview; Olie Lucas (Unang Hakbang Foundation), interview by IRM researcher, 6 March 2024; Catherine Ruiz (Kaabag sa Sugbo Foundation), interview by IRM researcher, 8 March 2024.

[6] Patricia Sarenas (Chair of PH-OGP Non-Government Steering Committee), interview by IRM researcher, 12 February 2024; Ruiz, interview; Czarina Medina-Guce (Ateneo de Manila University), interview by IRM researcher, 12 March 2024.

[7] Soliman, interview; Lucas, interview; Ruiz, interview.

[8] See Chapter 2 in: Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government Partnership, December 2023, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Philippines_Action-Plan_2023-2027_December.pdf, 210.

[9] See Chapter 2 in: Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More, 15.

[10] Raizsa Mae Anayatin (Mindanao Coalition of Development NGO Networks), interview by IRM researcher, 12 February 2024.

[11] Ruiz, interview.

[12] Sheryll Grace Aromin, John Axl Acordon, Luchvez, Lovely Palisoc, and Cedie Del Rosario (Department of Budget and Management), interview by IRM researcher, 15 April 2024.

[13]Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government Partnership; Bautista, interview.

[14] See Chapter 2 in: Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government Partnership, 15–17.

[15] See Annex G in: Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government Partnership, 211.

[16] Richar Villacorte and Pearl Clemente (Department of the Interior and Local Government), interview by IRM researcher, 5 April 2024.

[17] Median-Guce, interview.

[18] Medina-Guce, interview.

[19] See Annex E in: Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government Partnership, 192–94.

[20] See Chapter 2 in: Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government Partnership, 17.

[21] Ruiz, interview.

Geruld Reply

See Chapter 2 in: Sixth OGP National Action Plan 2023–2027, Philippine Open Government Partnership, 15–17.