Republic of Korea Action Plan Review 2023-2027

The action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... includes promising commitments on administrative appeals, access to government data, and whistleblower protection—but its other commitments do not have clear potential for open government results. Given that this is the Republic of Korea’s first four-year plan, the government could consider revising the action plan to strengthen the commitments’ ambitionAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should “stretch government practice beyond its current baseline with respect to key areas of open government.” Ambition captures the po... and relevanceAccording to the OGP Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should include a clear open government lens. Specifically, they should advance at least one of the OGP values: transparency, citizen partic... to open government.

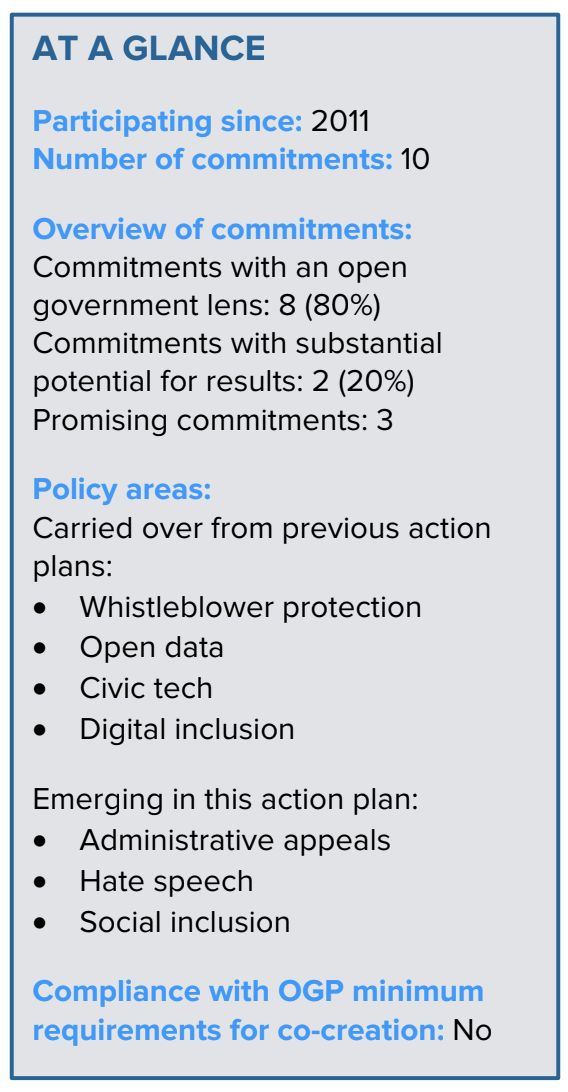

This report offers a review of the design of the Republic of Korea’s sixth OGP action plan, which has a four-year implementation period. The action plan includes 10 commitments intended to target anti-corruption, digital, and civic participation. It introduces a new focus on social inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More with Commitments 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10, but most of these initiatives have weak relevance to open government values. As a result, only 30% of commitments have clear potential for results (compared to 71% in the previous action plan).

This report offers a review of the design of the Republic of Korea’s sixth OGP action plan, which has a four-year implementation period. The action plan includes 10 commitments intended to target anti-corruption, digital, and civic participation. It introduces a new focus on social inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More with Commitments 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10, but most of these initiatives have weak relevance to open government values. As a result, only 30% of commitments have clear potential for results (compared to 71% in the previous action plan).

Co-creation was led by the Open Government Committee (OGC), the country’s multistakeholder forum (MSF), which was co-chaired by the Vice Minister of Interior and Safety and Transparency International – Korea. OGC expanded to include academic and private sector representatives, but civil society representatives constituted a smaller portion of the committee than the previous co-creation process. Following development of the action plan, in February 2024, OGC contracted to largely government, academic, and private sector representatives – with only one civil society representative.[1] The process for developing the action plan did not meet one of the minimum requirementsAll OGP participating countries are expected to adhere to the Participation and Co-Creation Standards. Each Standard includes clear and measurable minimum requirements that all OGP participating count... of the OGP Participation & Co-Creation Standards, as OGC did not provide stakeholders with sufficient reasoned responseOngoing dialogue between stakeholders during the development of an OGP action plan is critical to the plan’s success. Specifically, communicating back to stakeholders the ideas received and decision... to their contributions during co-creation. OGP instituted a 24-month grace period to ensure a fair and transparent transition to the updated standards, extending to 31 December 2023. As this action plan was co-created and submitted on 31 August 2023, it falls within the grace period.

This action plan was developed over a longer period than the previous plan, through an almost year-long consultative process. Several stakeholders noted that this offered more opportunity for civil society input.[2] Over a month-long contest, the government received 51 proposals from the public, as well as 37 government proposals. OGC narrowed these to 49 potential commitments it considered relevant to open government values.[3] OGC’s four Subcommittees on Planning, Anti-Corruption, Digital, and Civic Participation each considered these proposals through four rounds of discussion, eventually developing 22 draft commitments. Most meetings were not attended by the wider public or government agencies beyond the Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MOIS), although relevant agencies joined the fourth round of meetings[4] and shared written input through government platforms.[5] As the lead government agency, MOIS integrated government and non-government input. Following public discussions held during the Open Government Week with wider government participation, a two-week public consultation period, as well as an OGC discussion, the government approved the final 10 commitments—three of which (3, 7, and 8) were initiated by civil society and one was jointly proposed with government (1). Civil society stakeholders noted that participation in future co-creation processes could be improved by facilitating more direct dialogues between government and non-government stakeholders and inviting non-OGC members to subcommittee discussions.[6] The process would also be improved by providing reasoned response to all public proposals. This will be essential during the action plan’s refresh period at its halfway point,[7] and development of the next plan.

The action plan includes three promising commitments. By improving the usability of the administrative appeals system, CommitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 2 could substantially help people to remedy violations of their rights or interests by administrative agencies. Commitment 3 – one of the few commitments initiated by civil society – intends to more than double the amount of government data publicly available, and close citizen-identified gaps in government data provision. Commitment 1 continues important legislative work to strengthen whistleblower protection and financial support. However, beyond legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r..., efforts will need to address enforcement and social attitudes towards the whistleblower system to improve the commitment’s potential for anti-corruption results.

The potential for open government results of the remaining commitments is unclear. Most of the commitments on social inclusion have weak or no relevance to OGP values (5, 7, and 9). These commitments aim to help marginalized groups participate broadly in society, but do not seek to actively empower people to participate in government policies and decisions. Based on the OGP Articles of Governance, for commitments to be considered relevant to the OGP value of civic participation, governments must seek to mobilize citizens to engage in public debate, provide input, and make contributions that lead to more responsive, innovative, and effective governance.[8] Strengthening the ability to participate generally is not sufficient. Additionally, while relevant to OGP values, Commitments 4 ,6, 8, and 10 continue ongoing initiatives without indication of added value to existing practices.

Given that this is the Republic of Korea’s first four-year plan, the IRM recommends considering an amendment process to strengthen the commitments’ potential for results and OGP relevance. This is permitted within one year of the action plan’s submission.[9] Revised commitments could offer more detail on concrete actions to undertake during implementation. For commitments that are not aligned with OGP values, revisions could provide opportunities for marginalized groups to play an active role in implementation or incorporate information disclosure goals. Commitments that continue ongoing activities could be revised to scale up or further institutionalize efforts. If an amendment process is undertaken, the OGC could also consider adopting more ambitious commitments from the pool of proposals advocated by civil society during co-creation (such as decriminalization of factual defamation or opening energy data) or scaling up impactful commitments from the previous action plan. As noted by the Planning Subcommittee, it is vital to select more challenging tasks that are relevant to OGP with maturation and development in mind.[10]

Promising Commitments in Republic of Korea 2023–2027 Action Plan

The following review looks at the three commitments that the IRM identified as having the potential to realize the most promising results. Promising commitments address a policy area that is important to stakeholders or the national context. They must be verifiable, have a relevant open government lens, and have modest or substantial potential for results. This review also provides an analysis of challenges, opportunities, and recommendations to contribute to the learning and implementation process of this action plan.

Table 1. Promising commitments

| Promising Commitments |

| 1. Strengthen whistleblower protection and anti-corruption: This commitment plans to continue legislative work to strengthen whistleblower protection and financial support. It intends to amend the Act on Protection of Public Interest Reporters, along with four other laws that address compensation standards for different types of whistleblowers. |

| 2. Open and expand administrative appeals: This commitment would help people to remedy violations of their rights or interests by administrative agencies. It plans to make the complicated administrative appeals system more usable through a new online one-stop-shop. |

| 3. Fill data blanks and open list of closed public data: This commitment intends to more than double the amount of government data publicly available. It would disclose a substantial list of data that is held by government but not open to the public and use civic participation to determine what data to open. |

[1] As of February 2024, the Open Government Committee was reformulated with 23 members – 8 representatives from government and 14 from universities, think tanks, and the private sector, and 1 from civil society. See: “대한민국 얼린정부위원회” [Open Government Committee], Ministry of Interior and Safety, https://innovation.go.kr/ucms/main/contents.do?menuNo=300165# (accessed 21 March 2024).

[2] Lee Sang-hak (TransparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More International Korea), interview by IRM researcher, 17 November 2023; Kweon Oh-yeon (Code for Korea), interview by IRM researcher, 24 November 2023; Park Ji-hwan (Open Net), correspondence with IRM researcher, 4 December 2023.

[3] “Results of Open Government Committee’s 1st Evaluation of the Government/Public Proposals for 6th National Action Plan,” Open Government Committee Korea, 8 March 2023.

[4] Ministry of the Interior and Safety provided IRM with access to OGC subcommittee co-creation meeting minutes.

[5] Comments from Ministry of Interior and Safety during public comment period, 18 April 2024.

[6] Park Ji-hwan (Open Net), interview by IRM researcher, 18 October 2023; Lee, interview; Kweon, interview.

[7] The refresh period is an opportunity for stakeholders to reflect on the implementation of a four-year action plan, assess next steps, and determine a way forward to ensure ambition and results.

[8] “Articles of Governance,” Open Government Partnership, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/articles-of-governance.

[9] “OGP National Handbook,” Open Government Partnership, 2022, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/ogp-national-handbook-rules-and-guidance-for-participants-2022.

[10] “Planning Subcommittee 2nd Meeting Minutes,” Open Government Committee Korea, 14 March 2023.

Leave a Reply