Transparency and Accountability at the Frontlines of Justice: Citizen Oversight of Police

Transparencia y rendición de cuentas en la vanguardia de la justicia: Supervisión ciudadana de la policía

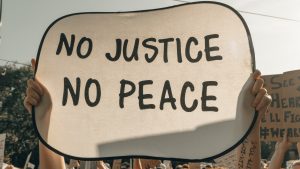

Photo Credit: Clay Banks via Unsplash

OVERVIEW

Recent civil unrest in the United States has exposed high levels of public distrust toward police, which similarly exists in many other countries. This distrust is particularly strong among minority communities, who often face disproportionate mistreatment at the hands of police around the world.

There are a variety of means by which citizens and communities can hold police accountable for their actions. These mechanisms include citizen advisory councils on policing policies and complaint mechanisms, community-oriented policing and partnerships, legal accountability mechanisms for when rights are violated, and participatory budgeting processes to determine future resource allocation.

- Oversight bodies give citizens a voice in how they are policed and in designing new ways to hold police accountable. They may operate at the local or higher levels. Oversight bodies may have a broad mandate, focus on controversial practices, or review police-citizen interactions and complaints.

- Partnerships and councils are flexible tools that can be adapted to fit their unique context. The goal of public-police partnerships is to bring together police with community organizations and individuals in order to build trust and improve public safety. They may often be part of community-oriented policing. The partnership approach has several goals that are consonant with principles of open government —collaboration, participation, and engagement. It is the most popular type of OGP policing commitments.

- Additional justiceTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi... mechanisms such as complaints tools, ombudsman’s offices, and improving liability regimes can improve how individuals or groups seek corrective action for mistreatment by police. In many OGP countries, the legal regime for police is unclear, with limited scope for legal recourse, leaving the public to depend on internal police discipline.

- Participatory budgeting is a process through which the public determines priorities and functions of public offices. As attention has shifted to the militarization of the police, budgeting processes have come to be seen as increasingly important in addressing crime, policing, and housing discrimination.

Across their various forms, oversight mechanisms need to be transparent in how members of the public can use them, who is a part of the decision making, and the results of citizen input. They must have a clearly defined mandate to direct police strategies and practices. When granted such authority, oversight bodies provide a vital form of police accountability and can help ensure policing strategies reflect citizens’ needs and priorities.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR GOVERNMENTS

Basic transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More

- Operating procedures: At a minimum, OGP members should make police operating procedures public, especially around controversial practices such as use of force, search and seizure, and control of protests.

- Several countries in Eastern Europe are using Freedom of Information requests to gain access to police operating procedures.

- Incident data: See Police Data Transparency section for detailed data on incidents.

- Incident disposition data: In addition, internal investigations should make final determinations public and transparent. All presumptions should be toward disclosure, with narrow and rare cases for officer privacy protection. Policies that determine which data is cleared for publication should be made public.

Public oversight bodies

- Practice and policy-level review

- Capacity buildingEnhancing the skills, abilities, and processes of public servants, civil society, and citizens is essential to achieving long-lasting results in opening government. Technical specifications: Set of ac...: Community panels may require advanced skills such as data analysis and legal understanding to best interpret appropriateness of policies. In other cases, training might be needed for facilitation, rule-setting, and documentation of decisions and notes. Community oversight bodies may have authority to review standard police operating procedures as well as controversial practices (e.g., use of force, search and seizure, and control of protests).

- Membership: Membership should be competitive, based on transparent criteria. Those criteria should aim for social representation, especially from groups who have historic or ongoing issues with policing as well as those with the capacity to oversee police (such as lawyers or community organizations).

- Example: An example of a public commission to oversee a particular practice was the Stop and Search Scrutiny Panel in the West Midlands, UK. Commissions operate across each of the 10 Local Policing Units of the region. These bodies meet independently and collectively.

- Complaints and officer-citizen interaction

- Mandate: Oversight bodies at the local level may oversee issues including excessive force, language, harassment, discrimination, theft, and failure to provide adequate or timely police protection.

- Public complaints: Citizens can file a complaint to the citizen review board (or to internal investigative affairs) to review incidents. Barriers to do so should be low, including for individuals with few resources or literacy. Tracking and disposition of complaints should be available to the individual.

- Review powers and authorities: Citizen oversight bodies may hold a mix of powers, including the ability to solicit, receive, consider, investigate, and publish determinations on public complaints. Such bodies need power to compel testimony and subpoena evidence to be fully effective. They should also be able to recommend various remedies, including mediation, arbitration, restoration, disciplinary action, or civil or criminal prosecution.

- Membership: Membership of such panels should be open and competitive, based on transparent criteria, which aims for social representation, especially from groups who have historic or ongoing issues with policing as well as those with the capacity to oversee police (such as lawyers or community organizations).

- Ombudsmen and citizen advocates. A special office can be created to advocate on behalf of the public. Representatives from this office may be members of an oversight body or may be independently or commission-appointed.

- Example: Newark, New Jersey’s (U.S.) Civilian Complaint Review Board collects and investigates concerns from the public regarding the police department. It also has the power to review disciplinary decisions and the department’s policies and practices.

Public-police partnerships and councils

- Communication and interaction: One element of community policing is having the police be present within the community and operating from a decentralized location.

- Engagement and collaboration: Police should engage with local agencies, organizations, and institutions to ensure that policing reflects community crime reduction goals. Engagement may focus onthe safety of communities who have a historic distrust of police such as migrants, ethnic minorities, people with disabilitiesA government is not open unless it is accessible to all, and governments are working to ensure people with disabilities are afforded equitable services and opportunities to participate. Technical spec..., victims of sexual assault, youthRecognizing that investing in youth means investing in a better future, OGP participating governments are creating meaningful opportunities for youth to participate in government processes. Technical ... More, or people experiencing homelessness.

- Example: In South Africa, Community Policing Forums (CPFs), composed of community members, organizations, and government authorities, monitor the effectiveness of the police and promote local police accountability.

Police accountability

- Standards and justiciability: Clear standards for policing can be laid out as part of the legal regime governing police-citizen interaction. This may cover excessive force, language, harassment, discrimination, theft, and failure to provide adequate or timely police protection. Clear rules and procedures on standing, materiality, forums, and the cost for bringing these complaints need to be detailed, publicly available, and easily discovered.

- Civil liability: Civil liability mechanisms establish processes for remedy and redress between plaintiffs and police agencies. Commitments and actions in this area would create standards and processes to ensure that there is accountability for agencies that cause harm.

- Criminal liability: Some jurisdictions will choose to make individual officers criminally liable for serious violations of the law, especially in cases of violent crime.

- Independent forums: OGP members can take steps to strengthen or establish independent forums to hear legal challenges to police operations. These will be more effective if they are independent of internal police review bodies or regular prosecutorial officers (who depend on police for investigations and prosecutions).

Open and participatory budgeting

- Determining allocation of services: At the time of publication, there is increasing discussion on resource allocation in the United States. For example, there is discussion about moving resources to conflict resolution, mental health, social work, and homelessness services. Some of this is being done through open city council meetings, as has happened with the People’s Budget in Nashville, (US). In other cases, participatory budgeting mechanisms have been used to discuss shifting resources, as in Los Angeles, New York, and Boston.

- Including affected communities: Participatory budgeting without intentional outreach might miss including those most affected. Positive examples include communities working on responding to crime in Merseyside, UK and working with citizens reentering the community from incarceration in Canada. These can empower people at the center of police-citizen interaction.

- Ample time for public voices: An important element of participatory budgeting is that grassroot community members can speak for the majority of budget conversations. Studies show that this significantly affects the quality and outcomes. A key part of this has been the development of peoples’ budgets, which are budget proposals by various grassroot organizations.

INTERNATIONAL NORMS AND GUIDANCE

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Handbook on Police Accountability, Oversight, and Integrity

This 2011 report covers a variety of internal and external mechanisms to strengthen police accountability. Specifically, the report offers recommendations regarding complaints against the police, independent oversight and complaint bodies, internal accountability, accountability to the state, and engaging the public.

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human RightsAn essential part of open government includes protecting the sacred freedoms and rights of all citizens, including the most vulnerable groups, and holding those who violate human rights accountable. T..., New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing

This 2019 U.S. report includes recommendations on community policing, responding to crises, the U.S. first amendment and free speech, accountability, and police data.

Organizations for Security and Cooperation in Europe

OSCE offers guidebooks on Good Practices in Building Police-Public Partnerships (2008), Democratic Policing (2007), and Human Rights Education for Law Enforcement Officials (2012).

The National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement, “What are the features of an effective police oversight body?”

NACOLE (U.S.) recommends several key features for effective public oversight including sufficient independence, funding, authority, access to information and decision makers, transparency, and community outreach.

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

The 2019 Law Enforcement Best Practices: Lessons Learned from the Field report provides guidance for implementing a community policing approach. The 2009 Standards and Guidelines for Internal Affairs: Recommendations from a Community of Practice focuses on internal complaint review and resolution processes.

Human Rights Watch, Shielded from Justice: Police Brutality and Accountability in the United States

This 1999 report investigates patterns of police abuse and accountability across 14 American cities. It highlights obstacles to successful civil and criminal lawsuits regarding police misconduct.

OGP COMMITMENTS IN THIS AREA

There are a number of OGP commitments dealing with citizen and police interaction. They are exclusively focused on partnerships and community-oriented policing. At this time, there are no commitments on oversight bodies (at any level) nor specific justice mechanisms to encourage public oversight of police actions.

- Afghanistan (2017–2019): The Ministry of the Interior expanded Public-Police Partnership Councils to all remaining provinces after initial success in 23 provinces.

- Georgia (2016–2018): The Prosecutor’s Office of Georgia established local councils composed of representatives from law enforcement, municipalities, legal organizations, and nongovernmental organizations to coordinate crime prevention measures.

- Panama (2015–2017): Panama committed to creating advisory councils made up of the National Police, citizen security organizations, and representatives of civil society to create and strengthen new citizen security programs.

- Ukraine (2016–2018): Government, civil society, and international partners coordinated to train law enforcement officers in community policing practices, launch a complementary public awareness campaign, establish citizen advisory groups, create online resources for police-community coordination, and implement a “schools and police” project.

- Jalisco, Mexico (2017–2019): This commitment sought to create spaces for dialogue and coordination between neighborhood councils and local police in the Lomas De Polanco neighborhood in Guadalajara, Mexico to improve citizen trust in police.

RESOURCES AND PARTNERS

- Campaign Zero lists policy recommendations for community oversight of police and provides several databases aggregating and visualizing relevant police data:

- Use of Force Project aggregates data on use of force policies across the United States, including comprehensive reporting requirements.

- California Police Scorecard Project grades police agencies based on several indicators including police accountability and civilian complaint outcomes.

- Mapping Police Violence aggregates data on police involved killings along with whether the officer was charged with a crime.

- Olugbenga Ajilore offers concrete recommendations in the article “How Civilian Review Boards Can Further Police Accountability and Improve Community Relations.”

- The Opportunity Agenda provides recommendations regarding various mechanisms for police accountability.

- U.S. General Services Administration, Office of Evaluation Sciences’ 2016 Community Action Deck: A discussion support tool for empowering communities to take action on the recommendations of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing outlines actions community reformers can take to work towards implementation of the recommendations from the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

- The American Civil Liberties Union’s Fighting Police Abuse: Community Action Model provides action-oriented guidance for community reformers.

Organizations

- African Police Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF)

- Campaign Zero (United States)

- Center for Policing Equity (United States)

- Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI)

- Igarapé Institute (Latin America)

- Instituto para la Seguridad y la Democracia (Mexico)

- Instituto Sou da Paz and Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública (Brazil)

- The National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement (United States)

- National Initiative for Building Community Trust & Justice (United States)

- Open Society Foundations

Our thanks to the Open Society Justice Initiative and Rebecca Neusteter at the University of Chicago for reviewing this module.

Featured Photo Credit: Clay Banks via Unsplash

Michelle Kosik Reply

It’s important to have justice to be held to account in order to prevent further criminal Misconduct in the government and abuse of power