United States Action Plan Review 2022–2024

- Action Plan: United States Action Plan 2022-2024 (December)

- Dates Under Review: 2022=2024

- Report Publication Year: 2024

The United States fifth national action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... is extensive; addressing a wide range of relevant public policy issues. However, it has overall limited potential to achieve significant change in government practices. Developed primarily through a top-down approach, it largely reflects government priorities rather than those of civil society. Many commitments are part of ongoing government initiatives or mandated by legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r.... Going forward, the government should establish a collaborative relationship with civil society to jointly develop, implement, and track commitments in line with OGP Participation and Co-Creation StandardsCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders is at the heart of the OGP process. The Participation and Co-Creation Standards are intended to support this collaboration throug....

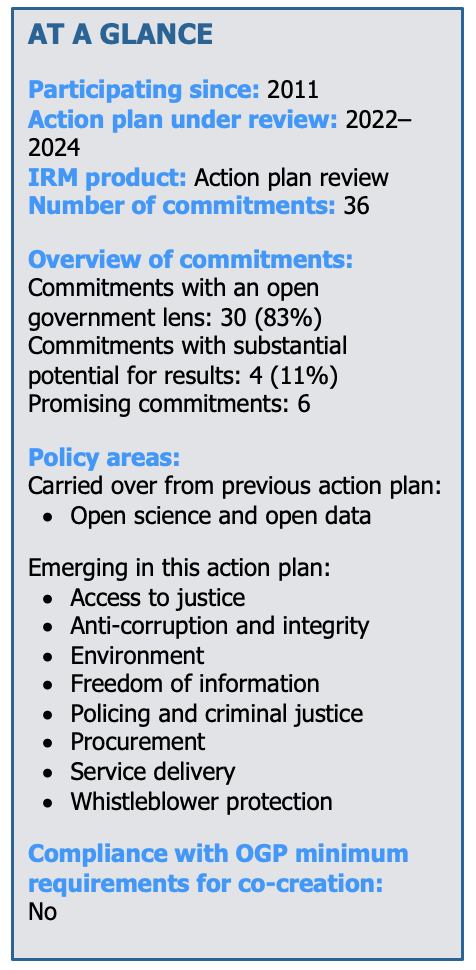

The U.S. fifth national action plan (NAP5) comprises 36 commitments organized into five areas: enhancing access to government data, research, and information (eight commitments); engaging the public (four commitments); improving government service delivery (five commitments); countering corruption and ensuring integrity and accountability (thirteen commitments); and ensuring equal access to justiceAccessible justice systems – both formal and informal – ensure that individuals and communities with legal needs know where to go for help, obtain the help they need, and move through a system tha... More (six commitments).

The U.S. fifth national action plan (NAP5) comprises 36 commitments organized into five areas: enhancing access to government data, research, and information (eight commitments); engaging the public (four commitments); improving government service delivery (five commitments); countering corruption and ensuring integrity and accountability (thirteen commitments); and ensuring equal access to justiceAccessible justice systems – both formal and informal – ensure that individuals and communities with legal needs know where to go for help, obtain the help they need, and move through a system tha... More (six commitments).

The plan encompasses several policy areas that were not in NAP4, which was shorter and primarily focused on open science and open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici.... These new areas focus on pressing issues such as environmental rights, access to justiceTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi... and freedom of information (the latter considered by civil society stakeholders an area of strategic concern). The policy area of open data and open science, carried over from NAP4, is now focused on social and racial equity.

The commitments are overall vague, making it challenging to understand how their implementation will contribute to achieving their intended aims. The action plan design process did not follow a logic model that included the identification of a problem to be addressed with an open government solution, a baseline, and clear demarcation of activities, milestones, deliverables, and responsibilities for implementation. As a result, of the 36 commitments, 6 are not relevant to open government, 19 lack specific activities or sufficient detail to determine their ambition and expected results, and only 4 have substantial potential for results.[1] Those that are relevant to open government focus mostly on making information more transparent, with half seeking to improve public participationGiving citizens opportunities to provide input into government decision-making leads to more effective governance, improved public service delivery, and more equitable outcomes. Technical specificatio....

The development of NAP5 was led by an Open Government Working Group which included officials from the General Services Administration (GSA), the Executive Office of the President, the U.S. Department of State, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. Points of contact were designated for each of the NAP’s five themes.[2] The working group obtained input and feedback from agencies on proposed commitments and selected the commitments that made it into the plan. The GSA was responsible for soliciting civil society input and publishing the action plan.

The NAP5 co-creation process was expected to help restore relations between civil society stakeholders and the federal government after years of significant tension during the previous administration and OGP action plan cycle.[3] Several CSOs had disengaged, expressing their loss of trust in the federal government’s commitment to open government principles and in the OGP process itself. The lack of engagement during the process to develop this plan exacerbated this position.[4] The Open Government Working Group did not include CSOs and had no designated multistakeholder forum.[5] According to consulted government officials, this was the result of legal restrictions that was not within their power to overcome.[6]

CSOs had limited opportunities for engagement. They primarily participated through responding to public requests for information and government-led virtual consultations referred to as “listening sessions”. CSOs largely perceived these opportunities as inadequate.[7] They emphasized that they had no say in determining which commitments should be included or excluded and did not play a role in defining the objectives, scope, activities, or milestones of the commitments ultimately included in the plan. They also pointed out that they received no reasoned response to their contributions. As a result, they disagreed with the government’s characterization of NAP5 as co-created with civil society. Some refused to re-engage stating they had so far seen no returns to their investment in the OGP process.[8]

The process did not address the majority of recommendations proposed by the IRM during the previous action plan cycle, which included to engage more fully and with a broader range of key stakeholders during the co-creation processCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders (e.g., citizens, academics, private sector) is at the heart of the OGP process. Participating governments must ensure that a dive..., and systematically respond to all proposed commitments and feedback on draft commitments; to designate a government agency to lead the process, clarify its duties, provide the tools that it needs to perform them effectively; to use a logic model to produce specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) commitments; and to demarcate responsibilities for their implementation to foster accountability.

Limited civil society engagement had implications on the quality and depth of the resulting NAP. The plan places more emphasis on government priorities, many of which are often part of previously planned or ongoing initiatives—some of them even approaching completionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More by the projected start of implementation. Commitments lack concrete activities, milestones, and expected outputs and results, and there is no tracking mechanism enabling civil society to monitor progress and hold the government accountable.

Going forward, the IRM recommends that the government collaborates with civil society to identify commitments with the most potential and transform them into SMART commitments. Given its size and scope, NAP5 lends itself to a filtering process that can yield a reasonable number of reformulated commitments with enhanced ambitionAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should “stretch government practice beyond its current baseline with respect to key areas of open government.” Ambition captures the po... and potential to generate significant results.

To that effect, Section II presents a selection of verifiable commitments with an open government lens that have been identified as promising due to their relevanceAccording to the OGP Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should include a clear open government lens. Specifically, they should advance at least one of the OGP values: transparency, citizen partic... to key stakeholders and to the national context as well as their potential to produce binding, institutionalized, or lasting change.

[1] For the full list of commitments and IRM coding, please see below Annex 1: Commitment by Commitment Data. For the full text of commitments, see: “Fifth U.S. Open Government National Action Plan,” White House, 29 December 2022, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/United-States_Action-Plan_2022-2024_December.pdf, p. 8.

[2] Anonymous government official, interview by IRM researcher, 6 June 2023.

[3] The U.S. was found to be acting contrary to the OGP process for not meeting the minimum participation requirements during the co creation of their fourth action plan. See: “United States – Contrary to Process Letter (March 2021),” Open Government Partnership, 22 March 2021, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/united-states-contrary-to-process-letter-march-2021.

[4] Alex Howard (Digital Democracy Project), interview by IRM researcher, July 2023; Anonymous civil society stakeholders, interview by IRM researcher, July 2023. Note: during the research process, several civil society organizations declined to respond to the IRM request for information stating their discouragement, fatigue, and lack of trust in the government and in the OGP process.

[5] Government representatives acknowledged the need to establish one. See: Philip Ashlock (General Services Administration), Presentation in virtual public meeting for the U.S. Open Government National Action Plan, 12 April 2022, https://open.usa.gov/meeting/april-2022-public-meeting.

[6] By law, recommendations from the public can only be requested and received in compliance with the requirements of the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which emphasizes public involvement through open meetings and reporting. According to government sources, since the publication of NAP5, GSA began to explore setting up a federal advisory committee to be able to solicit recommendations directly from public stakeholders, but the committee was not formed.

[7] Articulated by several members of civil society through interview, as well as in exchanges among civil society stakeholders in the online U.S. Open Government group.

[8] Anonymous civil society stakeholder 1, email correspondent with IRM researcher, 29 July 2023; Anonymous civil society stakeholder 2, email correspondence with IRM researcher, 31 July 2023.

Leave a Reply