Democracies Do Better in Pandemics, But Does Transparency Matter?

Before the global pandemic and especially early in 2020, political scientists, policy experts, and public health scholars told us, democracies do better in pandemics and in protecting public health generally.

So then, why did Belgium lead the news for a long time with the highest death rates anywhere in the world? In their defense, many Belgians said this was because they had one of the strongest statistical systems in the world, with a counting system that included cause of death.

Compare this with other countries, many of which have underdeveloped or less independent statistical agencies. According to the Economist, the excess death rate may, on average, be 2.3 to four times as high. The country listing of the two death counts (official and excess) are also quite dissimilar. Why? Some countries do not have the statistical capacity to count COVID-19 deaths, or simply cover up real figures. So, do we actually see a correlation between transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More and COVID-19 deaths? What if we had a way to measure that?

New data, new insights

Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, Alvaro Lopez, and their team at the Hertie School, a governance university based in Berlin, have developed such measures of transparency in recent years. The newly released T-Index is based on the direct observation of information on the websites that every country should have to enable good governance – from public expenditures or procurement contracts to ownership of firms, land or mining concessions. This index allows us to measure the degree to which governments proactively publish core data sets that prior research suggests are important to improving public integrity.

A suspicious trend

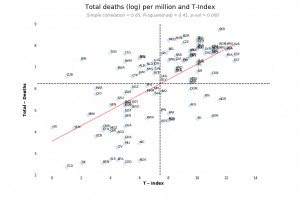

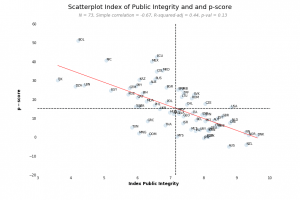

Using the T-Index and the official fatality data reported by countries and published by the World Health Organization, the researchers found a strong association (60% correlation) between higher casualties and transparency. Belgium, together with other countries with high transparency and high fatality, appears worse than countries like civil war stricken Yemen, which appear to have fewer deaths and low transparency (Figure A). The T-index is not significantly associated with the other death count (the excess deaths) where the better performance on the Index for Public Integrity is strongly correlated with lower excess death rates. The researchers also added controls for the age structure of the population, health expenditure, and even vaccination rates, which are all probable causes that can explain deaths by COVID-19.

Figure. Transparency and Death Rates

A. By official COVID death count. B. By excess death rates

What does this mean?

The implications of these findings in the Hertie School’s forthcoming paper are multiple.

- First, this continues to chip away at the pernicious myth that strongmen handle tough times better than democratic institutions. (Predicted here and later addressed here and here.)

- Second, this shows just how vitally important getting country systems for statistics and public health continue to be, especially as coronavirus shifts to becoming a disease of poorer nations, which are less resistant, less resilient, and more likely to suffer compound shocks.

- Third, it shows that continued investment and reform in good governance, including transparency, is not just a moral good from the perspective of freedom, but it also helps prevent premature death in the pandemic and beyond.

A short, draft version of the paper is available here. I encourage readers to engage with the draft paper and to send their comments to [email protected]

Comments (2)

Leave a Reply

Related Content

A Guide to Open Government and the Coronavirus

This guide is a one-stop shop for the best current resources on how open government projects and approaches can support tackling the pandemic.

OGP at Ten: Toward Democratic Renewal

When eight governments and nine civil society leaders launched OGP in 2011, no one expected it to reach its current size and scope. Over the last ten years, however, OGP…

Greg Michener Reply

Very interesting stuff, Joe. This seems to provide a bit of a disincentive for countries to keep good statistics on these sorts of things – better transparency (statistics) means higher death rates, which make leaders look worse – all else being equal. I will read the paper and maybe learn that I’m misunderstanding the implications. I recently wrote a piece comparing Trump and Bolsonaro’s approaches to public transparency – although a broader gauge, more academic perspective. Hope you’re keeping well.

Joe Foti Reply

Greg, great to hear from you. i think you are right in a certain sense. We know from many experiences (not naming names here) that there is incentive to focus on immediate relief over robust statistical capacity. In the worst cases, we know that there is even falsification or manipulation of data.

Where I think we need to have a nuanced approach is that decision-makers are going to respond to various incentives. There may be short term gains for information disinvestment or suppression, but I’m not sure that holds for the medium- and long-term. This is especially true when we begin looking beyond direct electoral politics. For example, if sovereign bond markets are pricing risk based on actual death rates, we would know that they are miscalculating risk. Rather, they would want to price based on state capacity (for both health and statistics) and for actual death, rather than published deaths.

But either way, I think the moral implication is that we need to continue to invest in statistical capacity, regardless of immediate political convenience.