Opening Up Extractives Contracting to Deter Corruption: What We’ve Learned

Increasing transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More, boosting the role of business, and deepening civic engagement in government contracting are powerful ways to deter fraud and corruption, craft better agreements, build trust, and promote a more competitive business environment. But how can we apply these principles to natural resource contracting, where big-ticket projects can be worth billions of dollars?

In a new report, the Natural Resource Governance Institute and the Open Contracting Partnership have collaborated to identify 16 good practices, illustrated by more than 30 real-world examples, that demonstrate how governments are harnessing transparency to improve the way they give out contracts, licenses, or permits for oil, gas, and mining projects. This list provides a ready inventory of smart and replicable interventions that OGP countries could draw on as they develop commitments to tackle corruption around natural resources.

We’ll be discussing the report and its application further at the OGP Global Summit next week, during a session entitled What Makes For Ambitious Commitments in the Extractives Sector? on Wednesday, July 18, from 2 p.m.-3:30 p.m.

Corruption in the processes by which governments award oil, gas, and mining rights to private companies can be extremely costly. To take just two examples from the past decade, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s “secret sales” of prime mining sites to anonymous British Virgin Islands-based shell companies may have resulted in government losses of USD $1.36 billion, while in Nigeria the award of licenses to a company controlled by a former petroleum minister, which then flipped them to international companies, possibly lost the government there hundreds of millions.

Transparency has emerged as a proven way to address corruption risks like these in other areas of government contracting. An August 2017 paper analyzing four million public procurement contracts in Europe showed that transparency was particularly effective at minimizing graft, especially where there is proactive disclosure of information before or during the process, rather than afterward. Elsewhere, a World Bank survey of 34,000 companies in 88 countries showed that competition was higher and kickbacks fewer and smaller in places where transparent procurement, independent complaint mechanisms, and external auditing are in place.

Given these risks, it is surprising that, until now, there has been a paucity of guidance for governments about how to open up processes by which they award and manage natural resource rights. The need for such materials is already clear. The governments of Ghana and Mexico made commitments to take an open contracting approach in their extractive industries at the 2016 U.K. anti-corruption summit, while the 2017 Africa Oil Governance Summit focused on “the role of open contractingA transparent procurement process, known as open contracting, increases competition, improves public service delivery, and ensures governments better value for their money. Technical specifications: C... More for efficient negotiation and revenue utilization.”

Our report aims to fill this gap. Here’s what we learned through our research:

1. It pays to get things right. Corruption risks can be costly, as noted above, but so too can the corrosive community relations that come from secret deals. A study from the Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School estimated that protests and community blockages could cost a major, world‐class mining project with a $3-5 billion capital expenditure roughly $20 million per week.

2. Smart, replicable practices exist. While established producers such as the provinces of New South Wales in Australia and Alberta in Canada, and the countries of Mexico and Norway feature many good practices from which we can learn, we also found excellent examples in developing countries and those at the frontiers of resource extraction, such as Guinea, Lebanon, and Sierra Leone. Moreover, no one country is doing everything right. Even among the best performers, there is still room for improvement.

3. The contracting chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Thinking about “openness” in the whole process of allocating and managing oil, gas, and mineral contracts is critical. This includes overarching issues such as the system and the actors involved; the planning process that informs which rights are awarded and how; the actual allocation and award process, whether it be through a competitive bid round/tender process or through rolling or first-come-first-served allocation processes; transparency of the contracts, licenses, or leases; and ongoing information on contract implementation.

4. Disclosure does not always equal transparency. Disclosure of ever-more information without improving comprehension and context might actually make a situation less transparent, burying the metaphorical needle in an even bigger haystack. Effective governments are therefore taking time to explain the system and the actors involved and joining-up information split across multiple government agencies to help those attempting to navigate it. In New South Wales, the government established a website, Common Ground, to help restore public trust after a series of scandals (in one case a coal seam gas exploration license was approved in a Sydney suburb without local consultation).

5. Consider all possible users. All too often, regulatory information is skewed toward the needs of industry at the expense of ordinary citizens, which can cause them to question the motives of the regulator. One agency that has gone to great lengths to balance the needs of various stakeholders is the Alberta Energy Regulator, who worked with the University of Pennsylvania to develop their approach. The results are telling: their 2017-2018 AER annual report notes 82 percent of Albertans and 77 percent of stakeholders expressed confidence in the AER.

6. Implement the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Many of the practices documented in our report are already addressed by the EITI Standard. These include requirements relating to information on the licensing process, production, revenue collection and social and economic contributions, and the encouragement of contract disclosure. Since its inception, OGP has encouraged its resource-rich members to commit to joining EITI. OGP and EITI recently signed a memorandum of understanding to formally align their complementary spheres of work.

7. The biggest informational challenges remain at the project level. Our review showed that it is still difficult to find systematic ongoing disclosures of implementation data disaggregated by project. Implementation of the EITI’s project-level payment disclosure requirement clarified by the EITI board in 2017 will be an important tool in this respect.

Similar gaps exist with respect to the project-specific rules and commitments contained in contracts, licenses or permits. While governments in over 40 countries have now published at least some contracts, comprehensive disclosure comprising the full text of contracts, their annexes, and any amendments is still comparatively rare; fewer than 20 countries do this in even one sector.

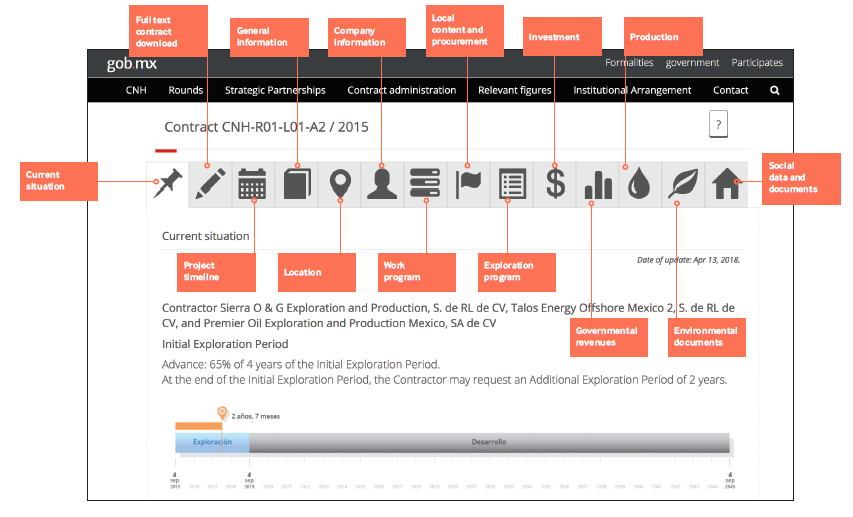

The best example of an architecture for joined-up project-level information comes from Mexico’s Rondas México website, which features a dedicated page for each awarded contract. In addition to the main contract and related documents, environmental documents and work plans, each contract page contains a range of tabs users can navigate to find a range of additional information. This includes details about the allocation process under which the contract was awarded and information on the implementation stage, including project-level data on local content and procurement, investment, government revenues and production levels.

—

If you have any feedback, or you are interested in discussing how you can apply these findings in your country, you can reach us at [email protected], [email protected] or [email protected].

Gavin Hayman is the executive director of the Open Contracting Partnership. Rob Pitman is a governance officer with the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Amir Shafaie is the director of legal and economic programs at NRGI.