Peixoto and Fox’s “When Does ICT-Enabled Citizen Voice Lead to Government Responsiveness?”

In my research for the ‘Transparency for Development’ social accountability project, I came across Fox and Peixoto’s backgrounder for the 2016 World Development Report. Their paper “reviews evidence on the use of 23 information and communication technology (ICT) platforms to project citizen voice to improve public service delivery… [focusing] on empirical studies of initiatives in the global South, highlighting both citizen uptake (‘yelp’) and the degree to which public service providers respond to expressions of citizen voice (‘teeth’).” Here are some of my key takeaways from their work, which I found extremely timely and useful (especially considering the essays Thomas Carothers collected for Carnegie this May on “Ideas for Future Work on Transparency and Accountability“).

(1) Access to information ≠ accountability

This is a not infrequent fallacy that the open government field needs to bear firmly in mind. Just because citizens have more information (through, say, an ICT portal) about a problem, government policy, or policymaker behavior, does not necessarily mean they will have the power or motivation to act.

In light of widely held unrealistic expectations about the ‘power of sunshine’, convincing propositions about causal mechanisms involved need to specify how and why the availability of an ICT platform (a) would motivate citizen action and (b) why the resulting user feedback would motivate improvements in service provision. After all, decisionmakers’ lack of information about problems is not the only cause of low-quality service provision.

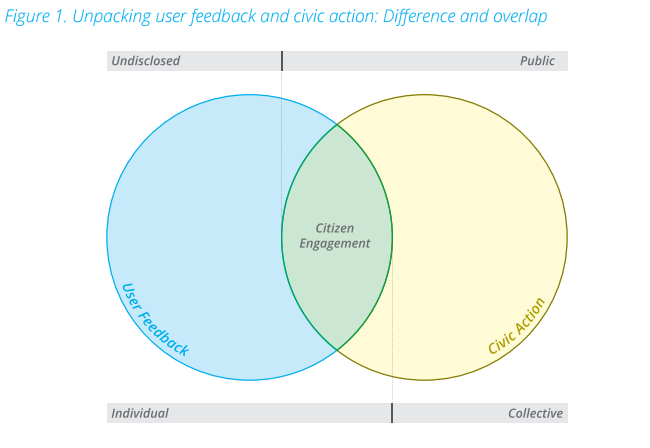

(2) User feedback ≠ civic action

Here, the authors draw the distinction between these two mechanisms by which citizen voices (can) affect service provision. In the former, citizens complain about individual user experiences to call for policymakers to hold the offending service providers accountable, but does not necessarily make the complaint public. The latter, on the other hand, intends to aggregate citizen opinions into publicly available, politically significant ‘asks’ around a cause or policy preference. Where the the two overlap, Fox and Peixoto define as ‘citizen engagement’.

(3) Uptake ≠ responsiveness

Whereas the first two takeaways were from the authors’ theoretical model, this one comes from their actual findings, and is perhaps the most important. Citizen use of this sort of ICT platform should not be equated to institutional responsiveness to their complaints or requests (as some development practitioners are wont to do). Furthermore, high usage rates do not necessarily lead to institutional responsiveness. Peixoto and Fox’s sample includes several major cases where citizens used new platforms at rates that exceeded expectations but still met with silence from above. In fact, more than half of the cases in their sample had low institutional responsiveness.

Frustratingly, the authors were not able to identify a ‘magic bullet’ factor that clearly led to government responsiveness. Instead, these platforms’ success seems to depend on “multiple pathways to institutional responsiveness – involving the convergence of multiple, mutually reinforcing factors”. This provides further evidence that social accountability, and the use of technology to facilitate it, is a complex, non-linear, and moving target.

You can read the full paper here, courtesy of the World Bank, or an abridged HTML version via the IDS Bulletin.