Making Trillion Dollar Stimulus and Safety Nets Work for All: The Essential Steps We Can Take Now

Billones de dólares en estímulos y redes de seguridad en beneficio de todos: Medidas esenciales que podemos tomar ahora

This blogpost was originally posted on the International Budget Partnership website. Click here to read the original blog.

A Societal Imperative

The magnitudes are staggering. To tackle the unprecedented healthcare emergency and lockdowns necessitated by COVID-19, governments are mobilizing the biggest stimulus and safety net packages we have seen since World War II. Governments and international institutions have announced at least $20 trillion in spending thus far in response to COVID-19. In the G20 countries, $6.3 trillion has been provided in fiscal support so far, representing 9.3 percent of G20 GDP. Germany’s fiscal and monetary stimulus is in excess of 40 percent of GDP! South Africa’s first round fiscal stimulus package is 10 percent of GDP. In Africa, over $114 billion in aid is needed to finance governments’ COVID-19 stimulus packages, of which half has been mobilized. These efforts dwarf the response to the 2008 global financial crisis.

Millions of lives and livelihoods are at stake. Rescue packages in each country have a different mix of fiscal, monetary and regulatory measures. Across countries they include massive procurements of life-saving medical supplies and medicines that touch the lives of all citizens; safety nets for millions of vulnerable people; subsidies and credits to protect jobs for thousands of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME); and major infrastructure investments, taxPlacing transparency, accountability, and participation at the center of tax policy can ensure that burdens are distributed equitably across society. Technical specifications: Commitments related to c... and regulatory incentives to provide employment for millions. For instance, Nigeria’s $6 billion package aims to provide a safety net for 30-60 million vulnerable households, job protection for half a million in 50,000 MSMEs, and employment for over a million through rural roads projects. Effectiveness of these surpluses is not just of profound economic and social significance – it is a moral imperative. It is also a vital opportunity for governments to build back and sustain citizen trust, which had plummeted to historic lows prior to the pandemic.

But history also tells us that when money moves as fast as in the COVID-19 response there is a risk of corruption, capture, and failure to reach those who need help the most. And we have already seen early signs of these with COVID-19 funds in developed and developing countries alike. In Brazil, federal prosecutors have launched more than 400 investigations into suspected cases involving COVID-19 funds. In Colombia, 14 of the country’s 32 governors are suspected of corruption involving emergency COVID-19 funds. In the U.S., the incredibly wealthy L.A. Lakers franchise valued at $4.4 billion received $4.6 million from the payroll protection program targeted to small businesses.

Even prior to the pandemic, the track record of many countries is that public spending does not reach many of the intended beneficiaries; the funds “leak”. For instance, 70 percent of the recipients of Sri Lanka’s Samurdhi program for the poor were in fact not poor. Simply scaling up existing safety net programs may not ensure that vulnerable groups receive vital COVID-19 assistance.

The Open Government Approach

To mitigate these risks and achieve their vital goals, an open governance of these massive stimulus and safety nets is essential. Openness, which enables citizens, civil society, businesses to shape programs and “follow the money.” This offers a unique approach by combining government transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More with the active participation of citizens, civil society and oversight institutions to ensure that funds achieve their intended purposes.

This is a central thrust of what government reformers and civil society activists have sought to accomplish through the Open Government Partnership (OGP) over the past decade. The reforms they have co-created and implemented provide excellent innovations and learning which can be applied to COVID-19 stimulus and safety net packages. For instance:

- Through Italy’s Open Coesione Platform, the government disclosed details of one million projects supported by 100 billion euro of EU financing and then launched a massive public information campaign to empower citizens, including high-school students, to be on-the-ground monitors of projects.

- Through the Philippines’ Open Roads Initiative in 2014, the government disclosed details of road expenditures, often geo-coded. Citizens and civil society carried out social auditsInstitutional and legal frameworks are necessary for providing assurance of the integrity of financial information and of compliance with budgetary rules and procedure. Technical specifications: These... on the existence and condition of roads, and the formal audit institution used the citizens’ social audits to mandate a government response, saving $300,000 per ghost road identified.

- Through the Citizen Eyes and Ears mobile app in Kaduna, Nigeria, the government discloses the geo-location of publicly funded projects and citizens upload photos and feedback on these projects which go directly to the Governor’s office and State Legislature for corrective action.

Stages of Design and Implementation of Stimulus & Safety Nets

These open government approaches can be applied to different stages of design and implementation of COVID-19 stimulus and safety nets packages. They offer an unprecedented opportunity to start to rectify societal inequities that have been laid bare by the pandemic and build a more just recovery. This can’t happen without a transparent and inclusive process.

Open Decision-Making. To begin with there must be total transparency in the decision-making process. Government needs to be open about who gets the money (including tax and regulatory exemptions), how that was decided and where the funds are coming from. It is vital to ensure that the stimulus policy-making process is evidence-based and inclusive, particularly to amplify the voice of historically marginalized groups and others facing added vulnerabilities due to COVID-19. Any interested member of the public should be able to inform those decisions directly, and the lobbyingLobbying transparency allows the public to ensure that there is diversity of participation and contribution to public decision-making. Technical specifications: Policies and actions affecting lobbying... that accompanies policy and budgetary processes should be made open for all to see through transparent registers like those Chile and Ireland have instituted. Transparency in company ownership can provide oversight over whether bailouts, public contracts or regulatory exemptions are getting captured by the politically connected. Any company registered offshore, not paying their taxes, or undermining other social obligations should not receive support, as Denmark and Canada have instituted.

Open AidMore and better information about aid helps partner countries and donor institutions plan and manage aid resources more effectively, parliaments and civil society to hold governments accountable for t.... The terms of the billions of dollars in grants and loans to finance COVID-19 response and recovery from International Financial Institutions such as the World Bank and IMF, and other incurred debtOpenly disclosing information about government debt enables informed decision-making, mitigates the risk of financial instability, and allows citizens to hold their governments accountable for respons... More, should be made open. All financial flows should be disclosed according to aid transparency best practices, along with specific targets of what they are intended to accomplish and who they seek to reach. This will start to balance the necessary focus thus far on mobilizing international aid with now an equally concerted attention on how well the money raised is being used to achieve its intended purposes.

Open Budgets. Following an open decision-making process on who the target for support is and where the money is coming from, ministries of finance need to disclose their expenditures, including emergency COVID-19 spending, in regularly updated open data, as the U.S. did for the $800 billion Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. This already poses a challenge because the Open Budget Survey (OBS) for 2020 highlights that three-quarters of the 117 surveyed countries do not have sufficient levels of budget transparency according to the basic minimum standards set in accordance with international norms.

Transparency and Oversight of Safety Nets and MSME Support. Beyond overall budget transparency, transparency in safety nets and engagement and oversight by groups representing the least resilient and those hardest hit by the pandemic can ensure that these funds actually reach the intended beneficiaries. For instance, the Philippines government has released a $4 billion “social amelioration package” for COVID-19. But ensuring these precious resources are not siphoned by corruption and actually reach the targeted 18 million vulnerable — senior citizens, people with disabilitiesA government is not open unless it is accessible to all, and governments are working to ensure people with disabilities are afforded equitable services and opportunities to participate. Technical spec..., pregnant women, indigent indigenous people, and the unemployed — will require transparency, participation and oversight on who is eligible and a citizens’ grievance redressal mechanism, mediated by the vigilant Filipino civil society and overseen by formal accountability institutions. Similarly, transparency and monitoring by business associations is needed to ensure that support in stimulus packages reach targeted MSMEs. This is a key emerging focus in the design and monitoring of South Africa’s package where smaller MSMEs in distress could not access the initial credit guarantee scheme.

Open Contracts. Governments also need to ensure that all procurement processes are open and competitive – from the tender to execution. Yet less than one-third of countries have taken steps to publish contracting data. This poses a particular risk of price gouging and corruption in times of COVID-19, even jeopardizing lives. As New York desperately struggled to acquire ventilators, it paid – through an opaque contract – a whopping $69 million for 1,500 ventilators at triple the retail price; tragically, none were even delivered. Open contracting and open spending empowers citizens, journalists and civil society to follow the money and become the government’s eyes and ears on the ground. For instance, in Paraguay and Colombia, the government publishes emergency contracts as open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici... that civil society monitors, including by tracking price differences for COVID-19 supplies. For public contracts in stimulus packages more broadly (e.g., for infrastructure projects), open contractingA transparent procurement process, known as open contracting, increases competition, improves public service delivery, and ensures governments better value for their money. Technical specifications: C... More can save money, fight corruption and spur economic activity. Through Ukraine’s open contracting platform over two years, citizens flagged 14,000 violations, the government saved $1 billion, 82% of entrepreneurs reported reduced corruption, and there was a 50% increase in contract bids, including from MSMEs.

Formal Oversight Institutions. At the heart of an open government approach is a partnership of government with citizens, civil society and accountability institutions. Formal oversight, audit functions and whistleblower protections are essential. All stimulus spending should be audited by independent institutions, and regular reports made to parliament. In this regard, there are important opportunities for audit institutions to collaborate with civil society in value-for-money audits or following the money, such as the Philippines’ Commission of Audit using citizens’ social audits under the Open Roads Initiative. Where corruption is uncovered, prosecutions should be made. Where nefarious political influence is suspected, the media should be free to report.

Participation & Monitoring by Citizens, Civil Society & Businesses. Beyond formal oversight mechanisms, government, civil society and business associations need to shape and monitor packages to ensure that they have the desired impact. This means grassroots groups monitoring infrastructure projects, checking that those vulnerable households eligible for safety nets and cash transfers get their support (while respecting right to privacy), and informal sector businesses who may not be on the government’s radar receive targeted MSME support. A particularly important imperative is to empower civil society groups representing the marginalized and vulnerable groups to amplify their voice in shaping and monitoring COVID-19 safety net programs. In Africa, the Follow the Money network of civil society organizations is tracking COVID-19 related spending, including aid flows, to ensure it is reaching those it is intended to help. These youthRecognizing that investing in youth means investing in a better future, OGP participating governments are creating meaningful opportunities for youth to participate in government processes. Technical ... More civil society organizations are also leveraging social media and digital technology to solicit beneficiary feedback.

Where civil society uncovers corruption, waste or poor implementation government must commit to address those deficiencies quickly to close the feedback loop. Only then will governments be able to earn or sustain citizens’ trust.

Civic Space & Media Freedoms. For corruption and waste to be uncovered, the protection of civil liberties, basic freedoms of the press, and access to information must be sacrosanct. Unfortunately many countries have gone in the opposite direction by shutting down civic space, and restricting freedom of information. It is imperative to roll these back for effective design, implementation and monitoring of COVID-19 programs.

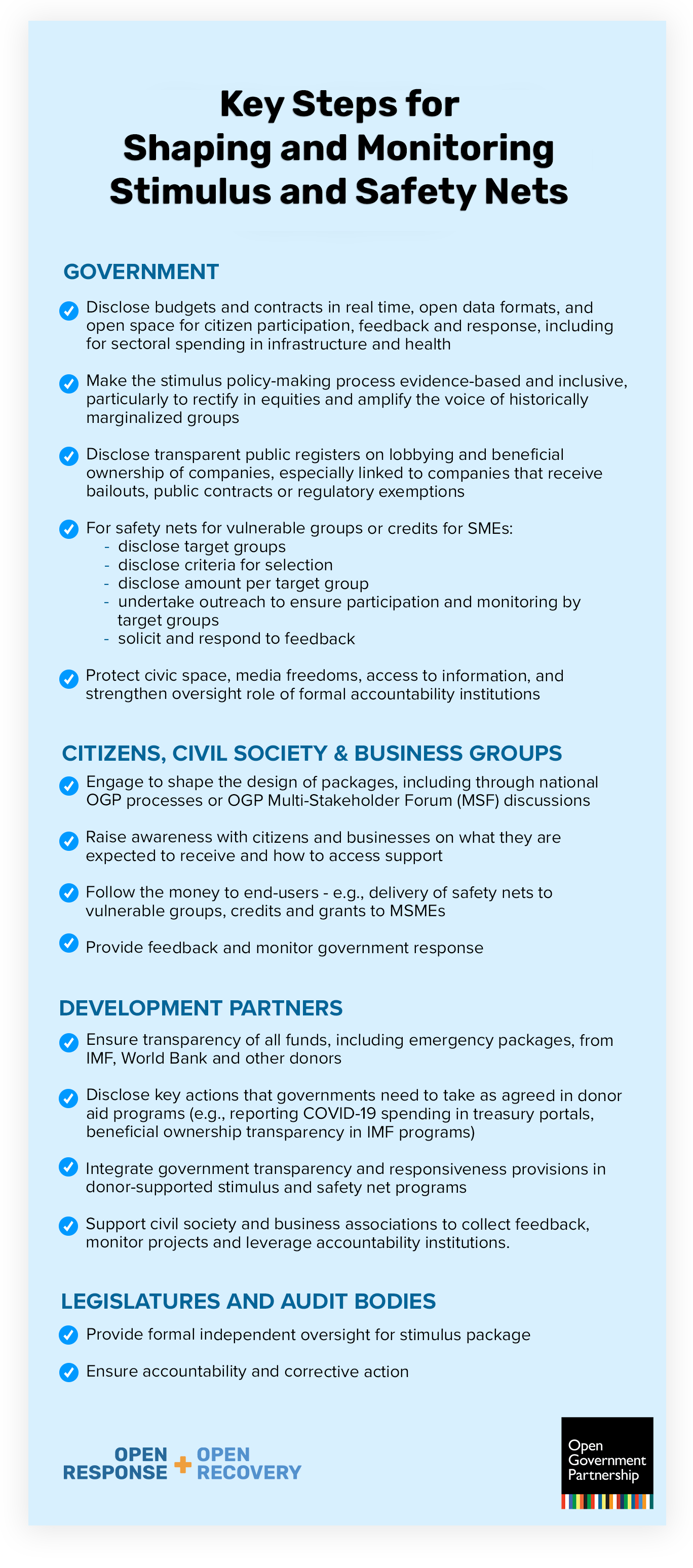

A Call to Action: The Essential Steps

For all of these measures to happen, we need a campaign in every country to monitor trillions or billions of dollars for millions of people, to ensure stimulus and safety net packages achieve their tremendous promise and imperative of saving lives and livelihoods. This requires complementary and mutually reinforcing actions by governments, civil society, business associations, accountability institutions, and international donors. Our call to action for each stakeholder group is summarized in the graphic below (see table). As citizens all over the world have been mobilized around curbing COVID-19 contagion, there is an unprecedented opportunity to now channel that attention and mobilize citizens and citizen groups to shape and oversee packages that will directly impact their lives. Indeed, with so many lives and livelihoods and such massive resources at stake, we need collective, collaborative leadership – a coalition of stakeholder groups to join forces and ensure that stimulus and safety nets flow through open governments, open budgets and open contracts through to the “last mile” of service delivery. If we do this, we won’t just ensure an effective COVID-19 response – we will build back a better governance system that will institutionalize openness and citizen oversight, sustain citizen trust by putting citizens at the heart of governance, and produce a more fair and just society for better times to come.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Rosalind and Ken Bensinger. “After One Tweet to President Trump, This Man Got $69 Million from New York for Ventilators.” BuzzFeed News, April 29, 2020.

Agence France-Presse. “World Bank, IMF: Africa Still Needs $44 Billion to Fight COVID-19 Pandemic.” Voice of America, April 17, 2020.

Aceron, Joy. “[Analysis] Challenges Facing Social Amelioration for the Coronavirus.” Rappler, April 1, 2020.

Arezki, Rabah and Shanta Devarajan. “Fiscal Policy for COVID-19 and Beyond.” Brookings, May 29, 2020.

Bailey Sr., Pam. “Finally, the Time is Ripe for SAI-Civil Society Collaboration.” International Budget Partnership, July 21, 2020.

Barkham, Richard, Spencer Levy and Darrin Mellott. “U.S. MarketFlash | COVID-19 Prompts the Largest Fiscal Stimulus in U.S. History.” Coldwell Banker Richard Ellis, March 27, 2020.

Barofsky, Neil M. “Why We Desperately Need Oversight of the Coronavirus Stimulus Spending.” The New York Times, April 13, 2020.

Bearak, Max. “Kenya’s Preexisting Condition: Mistrust in the Government.” The Washington Post, May 8, 2020.

Boccia, Romina and Justin Bogie. “This Is How Big the COVID-19 CARES Act Relief Bill Is.” The Heritage Foundation, April 20, 2020.

Bourgault, Shelby and Megan O’Donnell. “Ensuring Women’s Access to Cash Transfers in the Wake of COVID-19.” Center for Global Development, June 30, 2020.

Coronel, Sheila. “This Is How Democracy Dies.” The Atlantic, June 16, 2020.

Devex, “Funding the Response to COVID-19: Analysis of Funding Opportunities, 1 January to 19 July 2020.” July 21, 2020.

Drummond, Jaime. “The Vaccine Against COVID-Risk: Open Budgets, Open Response, Open Recovery.” International Budget Partnership, May 12, 2020.

Electronic Privacy Information Center. Stimulus Transparency Accountability Letter. April 21, 2020.

Ferreira-Rubio, Delia. “Tracking the Trillions: Monitoring Anti-Corruption Efforts at the International Monetary Fund Including during COVID-19 to Ensure Funds Reach Those Most in Need.” Transparency International, 2020.

Gates, Melinda. “The Pandemic’s Toll on Women: COVID-19 Is Gender-Blind, But Not Gender-Neutral” Foreign Affairs, July 15, 2020.

Gentilini, Ugo, Mohamed Almenfi, Pamela Dale, Ana Veronica Lopez, Ingrid Veronica Mujica, Rodrigo Quintana, and Usama Zafar. “Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures.” The World Bank and UNICEF, June 12, 2020.

Georgieva, Kristalina. “Confronting the Crisis: Priorities for the Global Economy.” International Monetary Fund, April 9, 2020.

Henningsson, Ebba and Jorge Rivera. “Diving Into the Data: Monitoring COVID-19 Emergency Funds in Africa.” ONE, July 16, 2020.

Human Rights Watch. “IMF: Make COVID-19 Funds Transparent, Accountable – Preventing Corruption Key to Helping Hardest Hit.” April 9, 2020.

International Monetary Fund. “Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” June 2020

International Monetary Fund. “How the IMF is Promoting Transparent and Accountable Use of COVID-19 Financial Assistance.” June 30, 2020

Keller, Janeen Maden, Julia Kaufman and Amanda Glassman. ”Accountability for COVID-19 Aid: Better Visibility Matters for the Quality of the Response.” Center for Global Development, May 1, 2020.

Lawal, Hamzat. “‘Following the Money’ During a Pandemic is Tough but OGP Could be the Game-Changer.” Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More, June 23, 2020.

Monbiot, George. “When Secret Coronavirus Contracts are Awarded Without Competition, It’s Deadly Serious.” The Guardian, July 15, 2020.

Okeowo, Gabriel. “Nigeria’s Spending Platform: Review, Gaps & Recommendations,” Budgit, 2020.

ONE, “COVID-19: How to Ensure Emergency Funds Reach Those in Need.” 2020.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19) Contribution to a Global Effort: Evaluating the Initial Impact of COVID Containment Measures on Activity.” March 27, 2020.

Pradhan, Sanjay. “Opinion: Open Response, Open Recovery.” Devex, June 18, 2020.

Ramkumar, Vivek. “Our Money, Our Responsibility: A Citizens’ Guide to Monitoring Government Expenditures.” International Budget Partnership, February 2008.

Salaudeen, Aisha. “Massive Funding Has Been Donated to Help Fight the Coronavirus in Africa. This Nonprofit Is Trying to Keep Track of It.” CNN, May 11, 2020.

Segal, Stephanie and Dylan Gerstel. “Breaking Down the G20 Covid-19 Fiscal Response.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, April 30, 2020.

Torbert, Sally. “A Call to Action on Open Budgets during the COVID-19 Response.” International Budget Partnership, May 7, 2020.

The World Bank. “World Bank Group and IMF mobilize partners in the fight against COVID-19 in Africa.” April 17, 2020

Un imperativo social

Las magnitudes son extraordinarias. Para solucionar la emergencia sanitaria y el confinamiento por COVID-19, los gobiernos están movilizando los estímulos y paquetes de redes de seguridad más importantes desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Los gobiernos e instituciones internacionales anunciaron que asignarán al menos 20 billones de dólares a la respuesta al COVID-19. En los países del G20, hasta el momento se han asignado 6.3 billones de dólares, lo que representa el 9.3 % del PIB de lo países del G30. En Alemania, ¡los estímulos fiscales y monetarios representan el 40% del PIB! La primera ronda de estímulos fiscales de Sudáfrica representa el 10 % del PIB. En África, se requiere más de 114 mil millones de dólares en asistencia para financiar los paquetes de estímulos asociados al COVID, la mitad de lo cual ya se movilizó. Estos esfuerzos eclipsan la respuesta a la crisis financiera global del 2008.

Millones de vidas y medios de subsistencia están en juego. Los paquetes de rescate de los países incluyen medidas fiscales, monetarias y regulatorias. Además, implican compras masivas de equipo médico y medicamento que son clave para la vida de todos los ciudadanos; redes de seguridad para millones de personas vulnerables, subsidios y créditos para proteger el empleo de miles de micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas (MIPyMES) e inversiones en infraestructura, iniciativas fiscales y regulatorias para ofrecer empleo a millones de personas. Por ejemplo, el paquete de 6 mil millones de dólares de Nigeria pretende ofrecer una red de seguridad a 30-60 millones de hogares vulnerables, proteger el empleo de medio millón de personas en 50 000 MIPyMES y ofrecer empleo a más de un millón de personas a través de proyectos de caminos rurales. La efectividad de estos excedentes no solo es de enorme importancia económica y social – es también un imperativo moral. Además, es una oportunidad clave para ayudar a los gobiernos a reconstruir.

Pero la historia nos recuerda que cuando los recursos se movilizan tan rápido como en la respuesta al COVID-19, se corre el riesgo de corrupción y de que el dinero no llegue a quien más lo necesitan. Ya se han registrado algunas evidencias de estos problemas en el caso de los fondos asignados a COVID, tanto en países desarrollados como en aquellos que están en vías de desarrollo. En Brasil, los fiscales federales han iniciado más de 400 investigaciones a casos sospechosos sobre fondos de COVID-19. En Colombia, 14 de los 32 gobernadores son sospechosos de casos de corrupción sobre estos fondos. En Estados Unidos, la franquicia de los L.A. Lakers, valorada en 4.4 mil millones de dólares, recibió $4.6 millones del programa de protección a nómina dirigido a pequeñas empresas.

Incluso antes de la pandemia, el historial de muchos países es que los recursos públicos, en muchos casos, no llegan a los beneficiarios a los que deberían; los fondos “se fugan”. Por ejemplo, el 70 % de los beneficiarios del programa Samurdhi de Sri Lanka para la reducción de la pobreza no eran en realidad pobres. En ese sentido, si solamente escalamos los programas de seguridad existentes, no podemos asegurar que los grupos vulnerables reciban la asistencia que requieren.

La propuesta del gobierno abierto

Con el fin de mitigar estos riesgos y alcanzar los objetivos planteados, es fundamental incorporar una gobernanza abierta en los paquetes de estímulos y redes de seguridad. La apertura permite a los ciudadanos, la sociedad civil y las empresas diseñar programas y “seguirle la pista al dinero”. Es un modelo único, pues combina la transparencia del gobierno con la participación activa de los ciudadanos, la sociedad civil y la supervisión de las instituciones para asegurar que los fondos logren los objetivos planteados.

Este es un elemento central a lo que los reformadores de gobierno y activistas de la sociedad civil han querido lograr a través de Open Government Partnership (OGP) en los últimos 10 años. Las reformas que han cocreado e implementado representan medidas innovadoras y lecciones aprendidas que pueden aplicarse a los estímulos y redes de seguridad a COVID-19. Por ejemplo:

- A través de la plataforma italiana Open Coesione, el gobierno ha puesto a disposición de la ciudadanía información detallada sobre un millón de proyectos con un valor de 100 mil millones de euros. Además, el gobierno lanzó una campaña masiva de información para empoderar a los ciudadanos, incluyendo a estudiantes de secundaria, para monitorear proyectos en campo.

- En 2014, la iniciativa de caminos abiertos de Filipinas llevó al gobierno a poner a disposición de la ciudadanía información detallada sobre los gastos de gobierno, en su mayoría con coordenadas geográficas. La ciudadanía y la sociedad civil llevaron a cabo auditorías sociales sobre la existencia y condición de los caminos. Por su parte, la institución oficial encargada de las auditorías utilizó los aportes ciudadanos para definir la respuesta del gobierno, logrando ahorros de US$300,000 por cada obra fantasma identificado.

- A través de la aplicación “Ojos y oídos ciudadanos” en Kaduna, Nigeria, el gobierno puso a disposición de la ciudadanía la ubicación de proyectos financiados con fondos públicos y la ciudadanía tuvo la oportunidad de enviar fotografías y retroalimentar estos proyectos directamente a la oficina del gobernador y a la asamblea legislativa para impulsar acciones correctivas.

Fases del diseño e implementación de los estímulos y redes de seguridad

Estos modelos de gobierno abierto pueden aplicarse a las diferentes fases del diseño e implementación de los estímulos y redes de seguridad diseñados para la respuesta al COVID-19. Representan una oportunidad única para empezar a corregir las desigualdades sociales que la pandemia ha descubierto y promover una recuperación más justa. Lo anterior no podrá ocurrir, a menos que se promueva un proceso transparente e incluyente.

Toma de decisiones abierta. En principio, debe haber una total transparencia en el proceso de toma de decisiones. El gobierno debe ser abierto sobre quién recibe el dinero (incluyendo estímulos fiscales y regulatorios), cómo se toman las decisiones y cuál es la fuente de los fondos. Es esencial asegurar que el proceso de diseño de políticas sobre los estímulos se fundamente en evidencias y sea incluyente. Además, se deberá incorporar las voces de los grupos históricamente marginados y aquellos a los que el COVID-19 ha debilitado. Todos los miembros del público deberán poder participar directamente en dichas decisiones y los procesos de cabildeo asociados a los procesos de diseño de políticas y creación de presupuestos debe ser abierto – todas las personas deben tener acceso a los registros de cabildeo, como lo han instituido Chile e Irlanda. La transparencia en los beneficiarios reales puede ayudar a identificar casos en que los fondos de rescate, contratos públicos o excepciones normativas son capturados por actores con conexiones políticas. Las empresas offshore, las que no pagan impuestos y las que no cumplen con sus obligaciones sociales no deberán recibir apoyo, como lo establecieron Dinamarca y Canadá.

Asistencia abierta. Es importante abrir los términos asociados a los miles de millones de dólares en donaciones y créditos que las instituciones internacionales financieras como el Banco Mundial y el FMI otorgarán para la respuesta al COVID-19. Todos los flujos financieros deben publicarse de acuerdo con las buenas prácticas definidas para la asistencia, así como las metas que buscan cumplir y los beneficiarios a quienes deben ir dirigidos los fondos. Además de movilizar la asistencia internacional, es importante evaluar la medida en la que los fondos están ayudando a lograr los objetivos planteados.

Presupuestos abiertos. Tras un proceso de toma de decisiones sobre los beneficiarios y las fuentes de los fondos, los ministerios de finanzas deben poner a disposición del público sus gastos, incluyendo las compras asociadas a la respuesta al COVID-19 en formato de datos abiertos y actualizarlos frecuentemente, como se hizo en estados Unidos en el caso de la Ley de Recuperación y Reinversión de 2009 en la que se asignaron 800 mil millones de dólares. Esto representa un reto: la Encuesta de Presupuestos Abiertos (OBS por sus siglas en inglés) de 2020 muestra que tres cuartas partes de los 117 países evaluados no tienen suficiente transparencia presupuestaria según los estándares mínimos definidos por las normas internacionales.

Transparencia y supervisión de las redes de seguridad y apoyo a las MIPyMES. Más allá de la transparencia presupuestaria en general, la transparencia en las redes de seguridad y la participación de los grupos menos resilientes y más afectados por la pandemia puede asegurar que los fondos sean recibidos por los beneficiarios. Por ejemplo, el Gobierno de Filipinas liberó un “paquete de alivio social” para el COVID-19 de 4 mil millones de dólares. Asegurar que estos recursos no sean tomados por la corrupción y que efectivamente sean recibidos por los 18 millones de personas vulnerables (adultos mayores, personas con discapacidades, mujeres embarazadas, personas indígenas y desempleados) requerirá de transparencia, participación y la supervisión de los beneficiarios, así como un mecanismo de retribución mediado por la sociedad civil de Filipinas y supervisado por una institución formal encargada de la rendición de cuentas. Asimismo, es necesaria la transparencia y el monitoreo de las asociaciones de empresas para asegurar que los paquetes de estímulos efectivamente sean recibidos por las MIPyMES. El diseño y monitoreo del paquete de estímulos incluye este tema como un elemento fundamental, pues las MIPyMES en situación precaria no pudieron acceder al esquema inicial de garantías.

Contratos abiertos. Los gobiernos deben asegurar que todos los procesos de compras sean abiertos y competitivos, desde la licitación hasta la ejecución. Sin embargo, menos de una tercera parte de los países han tomado medidas para la publicación de sus datos de contratación. Esto representa un riesgo de manipulación de riesgos y de corrupción, poniendo en riesgo la vida de las personas. En el momento en que Nueva York luchaba desesperadamente por comprar ventiladores, pagó – a través de un contrato opaco – 69 millones de dólares por 1 500 ventiladores, al triple del precio de distribución; trágicamente, no se entregó ningún ventilador. La contratación abierta y los gastos abiertos empoderan a la ciudadanía, a los periodistas y a la sociedad civil para seguir la pista al dinero y ser los ojos y oídos del gobierno en el campo. Por ejemplo, en Paraguay y Colombia, el gobierno publica los contratos de emergencia en formato de datos abiertos, los cuales son monitoreados por la sociedad civil, incluyendo el seguimiento a las diferencias de los precios de las provisiones para COVID-19. Para los contratos de paquetes de estímulos en general (por ejemplo, en proyectos de infraestructura), la contratación abierta puede ahorrar dinero, detener la corrupción y promover la actividad económica. A través de una plataforma de contratación abierta en Ucrania, los ciudadanos identificaron 14 000 irregularidades, el gobierno ahorró mil millones de dólares, el 82% de los empresarios reportaron una mejor corrupción y hubo un aumento del 50% en las licitaciones de contratos, incluyendo las MIPyMES.

Instituciones formales de supervisión. Un elemento central del gobierno abierto es la alianza entre el gobierno, la ciudadanía, sociedad civil y las instituciones encargadas de la rendición de cuentas. Además, la supervisión formal, la auditoría y la protección a denunciantes son fundamentales. Todos los recursos de los estímulos deben ser auditados por las instituciones independientes y deben enviarse informes frecuentes al parlamento. En ese sentido, existen oportunidades importantes para la colaboración entre las instituciones de auditoría y la sociedad civil, como el caso de la Comisión de Auditorías de Filipinas que utiliza las auditorías sociales bajo la Iniciativa Abierta de Caminos. Cuando se descubren casos de corrupción debe haber prosecución y cuando se sospecha que hubo influencias políticas, los medios deben reportarlo.

Participación y monitoreo por los ciudadanos, la sociedad civil y las empresas. Más allá de los mecanismos formales de supervisión, el gobierno, la sociedad civil y asociaciones de empresas deben definir y monitorear los paquetes de estímulos para asegurar que tengan el impacto deseado. Así, los grupos comunitarios pueden monitorear proyectos de infraestructura, verificando que los hogares más vulnerables son elegibles para recibir redes de seguridad y transferencias de efectivo (respetando su privacidad) y las empresas del sector informal que no estarían en el radar del gobierno recibieron apoyo dirigido a las MIPyMES. Una necesidad de particular importancia es empoderar a los grupos de la sociedad civil que representan a los grupos marginados y vulnerables, amplificando su voz para la creación y monitoreo de programas de COVID-19. En África, la red Sigue la pista al dinero, formada por organizaciones de la sociedad civil, está monitoreando los gastos asociados al COVID-19, incluyendo lo flujos de asistencia, para asegurar llegan a los beneficiarios definidos. Además, las organizaciones de la sociedad civil de jóvenes están utilizando las redes sociales y las tecnologías digitales para solicitar la retroalimentación de los beneficiarios.

Cuando la sociedad civil descubre casos de corrupción, desperdicios o implementación deficiente, el gobierno debe comprometerse a atender dichas deficiencias y cerrar el ciclo de retroalimentación. Solo así los gobiernos podrán ganarse y mantener la confianza de los ciudadanos.

Espacio cívico y libertad de medios. Para poder descubrir la corrupción y desperdicios, las libertades cívicas, de prensa y de acceso a la información deben ser intocables. Desafortunadamente, muchos países han hecho lo contrario, cerrando el espacio cívico y limitando la libertad de información. Para el diseño, implementación y monitoreo efectivo de los programas de COVID-19, es indispensable eliminar estas restricciones.

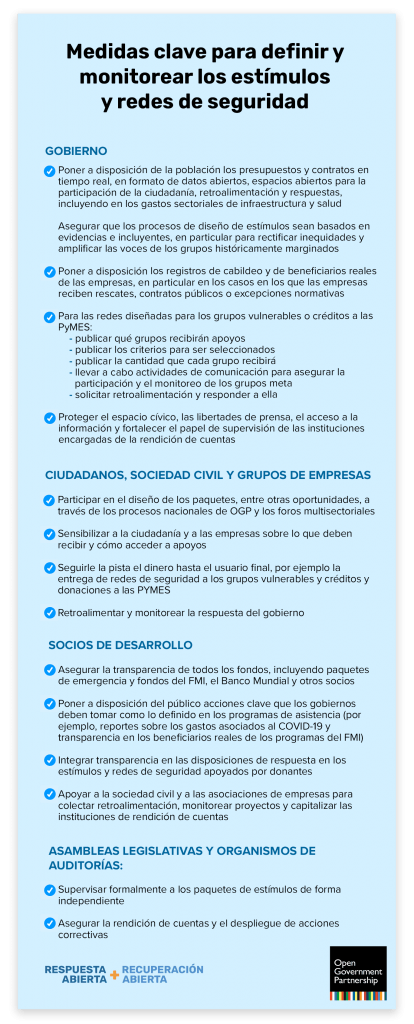

Un llamado a la acción: Medidas esenciales

Para que puedan ocurrir todas estas medidas, es necesario impulsar una campaña en todos los países para monitorear los billones o miles de millones que se destinarán a millones de personas, asegurando que los paquetes de estímulos y las redes de seguridad cumplan con la promesa de salvar vidas y los medios de subsistencia de todo el mundo. Lo anterior requiere de acciones mutuas y complementarias entre los gobiernos, la sociedad civil, asociaciones de empresas, instituciones encargadas de la rendición de cuentas y los donantes internacionales. En la siguiente gráfica presentamos nuestro llamado a la acción para cada actor. Los ciudadanos de todo el mundo se han movilizado para detener los contagios de COVID-19; en ese sentido, tenemos una oportunidad sin precedentes para canalizar la atención y movilizar a los ciudadanos y grupos de ciudadanos para definir y supervisar los paquetes que afectarán sus vidas. Con tal cantidad de vidas, medios de subsistencia y recursos en riesgo, necesitamos de un liderazgo colectivo y colaborativo: una coalición de actores uniendo fuerzas y con contratos abiertos a través de la última fase de la provisión de servicios. Si lo hacemos, no solamente aseguraremos que la respuesta al COVID-19 será efectiva, sino además reconstruiremos un sistema de gobernanza más sólido, institucionalizando la apertura y la supervisión ciudadana, manteniendo la confianza ciudadana y enfocando la gobernanza en la ciudadanía, creando una sociedad más justa y mejores tiempos.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

Adams, Rosalind and Ken Bensinger. “After One Tweet to President Trump, This Man Got $69 Million from New York for Ventilators.” BuzzFeed News, April 29, 2020.

Agence France-Presse. “World Bank, IMF: Africa Still Needs $44 Billion to Fight COVID-19 Pandemic.” Voice of America, April 17, 2020.

Aceron, Joy. “[Analysis] Challenges Facing Social Amelioration for the Coronavirus.” Rappler, April 1, 2020.

Arezki, Rabah and Shanta Devarajan. “Fiscal Policy for COVID-19 and Beyond.” Brookings, May 29, 2020.

Bailey Sr., Pam. “Finally, the Time is Ripe for SAI-Civil Society Collaboration.” International Budget Partnership, July 21, 2020.

Barkham, Richard, Spencer Levy and Darrin Mellott. “U.S. MarketFlash | COVID-19 Prompts the Largest Fiscal Stimulus in U.S. History.” Coldwell Banker Richard Ellis, March 27, 2020.

Barofsky, Neil M. “Why We Desperately Need Oversight of the Coronavirus Stimulus Spending.” The New York Times, April 13, 2020.

Bearak, Max. “Kenya’s Preexisting Condition: Mistrust in the Government.” The Washington Post, May 8, 2020.

Boccia, Romina and Justin Bogie. “This Is How Big the COVID-19 CARES Act Relief Bill Is.” The Heritage Foundation, April 20, 2020.

Bourgault, Shelby and Megan O’Donnell. “Ensuring Women’s Access to Cash Transfers in the Wake of COVID-19.” Center for Global

Development, June 30, 2020.

Coronel, Sheila. “This Is How Democracy Dies.” The Atlantic, June 16, 2020.

Devex, “Funding the Response to COVID-19: Analysis of Funding Opportunities, 1 January to 19 July 2020.” July 21, 2020.

Drummond, Jaime. “The Vaccine Against COVID-Risk: Open Budgets, Open Response, Open Recovery.” International Budget Partnership, May 12, 2020.

Electronic Privacy Information Center. Stimulus Transparency Accountability Letter. April 21, 2020.

Ferreira-Rubio, Delia. “Tracking the Trillions: Monitoring Anti-Corruption Efforts at the International Monetary Fund Including during COVID-19 to Ensure Funds Reach Those Most in Need.” Transparency International, 2020.

Gates, Melinda. “The Pandemic’s Toll on Women: COVID-19 Is Gender-Blind, But Not Gender-Neutral” Foreign Affairs, July 15, 2020.

Gentilini, Ugo, Mohamed Almenfi, Pamela Dale, Ana Veronica Lopez, Ingrid Veronica Mujica, Rodrigo Quintana, and Usama Zafar. “Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures.” The World Bank and UNICEF, June 12, 2020.

Georgieva, Kristalina. “Confronting the Crisis: Priorities for the Global Economy.” International Monetary Fund, April 9, 2020.

Henningsson, Ebba and Jorge Rivera. “Diving Into the Data: Monitoring COVID-19 Emergency Funds in Africa.” ONE, July 16, 2020.

Human Rights Watch. “IMF: Make COVID-19 Funds Transparent, Accountable – Preventing Corruption Key to Helping Hardest Hit.” April 9, 2020.

International Monetary Fund. “Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” June 2020

International Monetary Fund. “How the IMF is Promoting Transparent and Accountable Use of COVID-19 Financial Assistance.” June 30, 2020

Keller, Janeen Maden, Julia Kaufman and Amanda Glassman. ”Accountability for COVID-19 Aid: Better Visibility Matters for the Quality of the Response.” Center for Global Development, May 1, 2020.

Lawal, Hamzat. “‘Following the Money’ During a Pandemic is Tough but OGP Could be the Game-Changer.” Open Government Partnership, June 23, 2020.

Monbiot, George. “When Secret Coronavirus Contracts are Awarded Without Competition, It’s Deadly Serious.” The Guardian, July 15, 2020.

Okeowo, Gabriel. “Nigeria’s Spending Platform: Review, Gaps & Recommendations,” Budgit, 2020.

ONE, “COVID-19: How to Ensure Emergency Funds Reach Those in Need.” 2020.

Pradhan, Sanjay. “Opinion: Open Response, Open Recovery.” Devex, June 18, 2020.

Ramkumar, Vivek. “Our Money, Our Responsibility: A Citizens’ Guide to Monitoring Government Expenditures.” International Budget Partnership, February 2008.

Salaudeen, Aisha. “Massive Funding Has Been Donated to Help Fight the Coronavirus in Africa. This Nonprofit Is Trying to Keep Track of It.” CNN, May 11, 2020.

Segal, Stephanie and Dylan Gerstel. “Breaking Down the G20 Covid-19 Fiscal Response.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, April 30, 2020.

Torbert, Sally. “A Call to Action on Open Budgets during the COVID-19 Response.” International Budget Partnership, May 7, 2020.

The World Bank. “World Bank Group and IMF mobilize partners in the fight against COVID-19 in Africa.” April 17, 2020

Comments (1)

Leave a Reply

Related Content

A Guide to Open Government and the Coronavirus

This guide is a one-stop shop for the best current resources on how open government projects and approaches can support tackling the pandemic.

Open Response + Open Recovery

Our community’s fundamental values of accountability, transparency, inclusivity, and responsiveness are vital as we move through COVID-19 response to recovery. Find resources, events and examples from OGP and partners.

Challenges and Solutions

Challenges and Solutions Open Response, Open Recovery

OGP CEO Sanjay Pradhan writes about how the COVID-19 pandemic has compelled governments and citizens alike to take unprecedented, mitigating actions. In their shared struggle, mutual trust between government and…

Ottobong Peter Sambo Reply

To ensure COVID 19 response, recent events has revealed the activities government officials, Civil Society Organizations and representative of Development Partners must be tracked and monitored. Also, not only government need to open documents, all partners must adopt open approach for more fair and just society.